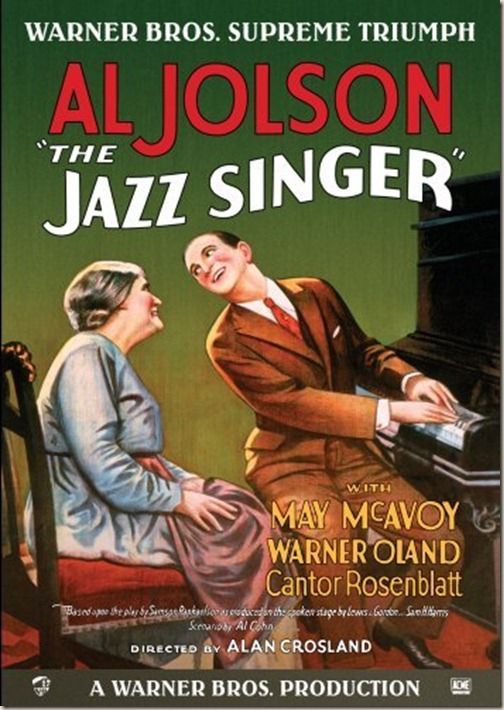

The

Jazz Singer

1927

Director: Alan Crosland

Starring: Al Jolson, May McAvoy

There

are many reasons that films are considered “Must See.” For many, it’s some certain inherent artistic

merit. For a few, it’s historical

relevance. In my opinion, The Jazz

Singer may not be loaded with artistic merit, but there is no denying

its historical relevance.

Jakie

Rabinowitz (Jolson) is the son of a cantor, and his family is very active in

their synagogue. His father has trained

Jakie in music with the intent of him taking over as cantor one day, but Jakie

loves to sing jazz. This eventually

causes his father to disown him, and Jakie changes his name to “Jack Robin” and

takes his act on the road. Striking it

big as a performer and meeting a pretty girl along the way (McAvoy), eventually

Jakie returns home to New York City to make his Broadway debut and tries to fix

things up with his pa. Naturally the

conflict between family and career is only heightened.

The

story is pretty standard, blatantly overtly sentimental fare. The acting is not acting but over the top

mugging. To quote my teenaged students,

“not gonna lie,” it gets pretty boring. The

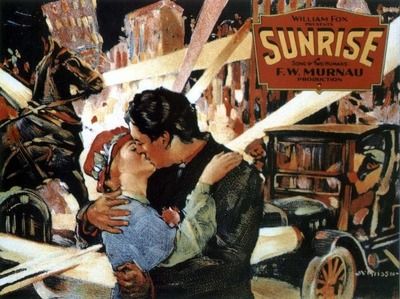

Jazz Singer is NOT gripping entertainment. It’s tough, especially when I compare it to

some of the stand out silent films from 1927, like Sunrise, The General, The Unknown,

and Metropolis. The Jazz Singer falls so

spectacularly flat in comparison. So to

me, if you’re looking for entertainment, go elsewhere, because I found precious

little of it in The Jazz Singer.

And

curiously, perhaps I should respond to the story because estrangement is,

unfortunately, a very real part of my immediate family history (and that’s all

I’m going to get into here). But there

was no wailing, no gnashing of teeth, no tearing of hair in the estrangement in

my family. Perhaps, then, I don’t react

well to films that depict it in this way.

Kind of a “been there, done that, doesn’t look at all like you’ve

portrayed it in your film.” So despite

what SHOULD be a bit of a personal connection to the story, I found absolutely

none.

But

I will never quibble with The Jazz Singer’s inclusion in any

kind of list that deals with significant film.

It’s hard to argue with “first feature length film that included sound.” There was no one change that so utterly

altered the landscape of film as the addition of sound, and The

Jazz Singer is a huge part of that change. It wasn’t that it was the first film to have

sound (there were shorts that preceded it that had audio songs), but its

enormous popularity – and the boatloads of money it made – signaled to the film

industry that audiences would eat up “talkies.”

A misconception to the general public is that The Jazz Singer is the

first all-sound film when it’s really a combination silent/sound film, with

nearly all the dialogue and dramatic scenes done in traditional silent film

style with intertitles, but the musical numbers are in sound. Originally only intending to include sound

for the musical numbers, Jolson improvised a dialogue scene with his mother in

between singing. This then made The

Jazz Singer the first film with recorded dialogue. When I first saw The Jazz Singer, I was

seeing films chronologically by decade.

I had been immersed in silent films (a fact that helped me appreciate

them better), and in all honesty, when Jolson talks to his mother, it was

rather magical. I can understand why

audiences at the time couldn’t get enough.

As Jolson famously ad-libbed, “You ain’t heard nothin’ yet!”

Beyond

its use of sound, however, The Jazz Singer also gets credit for

single-handedly inventing the movie musical.

After all, you can have silent comedies and silent dramas, but there’s

no way to make a silent musical. The first

sound picture burst on the scene with song and dance, and birthed an entirely

new genre. Vaudeville singers and

dancers found they had a place in Hollywood too. The outline of the backstage musical that The

Jazz Singer presents would be used again and again (and again and again

and again) throughout the ages – young person/couple/group has talent, starts

small, takes it on tour, gets a following, gets an opening in The Big Show,

gets opening night jitters and/or various complications, performs anyway and

knocks it out of the park. I honestly

won’t bore you with listing the films that use this general motif because they

are too many. And as a musical fan

myself, it’s important for me to appreciate that they all stem from The

Jazz Singer. There is no arguing

with that.

This

much is known pretty well to people who are aware of The Jazz Singer’s

historical significance. What I had

forgotten about, however, was the fact that this story plays out against the

backdrop of a traditional Jewish family.

I am not Jewish, but I have seen a lot of movies, and I have to say The

Jazz Singer’s portrayal of Jewish customs *seems* authentic (but again,

I am no expert, I am simply comparing it to other, perhaps more cartoonish

cultural representations). Moreover, no

one really makes a big deal that Jakie is Jewish. You could substitute in any religion and/or

culture, and you’d have the same story. Heck,

you could simply substitute in overbearing traditionalist father and leave

religion out of it, and you’d have the same story. And that’s a good thing. This is representative of a cultural

acceptance that is, frankly, a bit odd to find in a Hollywood movie from the

1920s (tempered, most definitely, by the blackface scenes, but still accepting in a way). Odd, but refreshing.

|

| Heck, Myrna Loy even pops up! |

The

Jazz Singer

is a film that I can’t in good conscience recommend. For those who have a passion for film

history, yeah sure, see it, knock yourself out.

For the casual film fan, really, there’s no need to see it. You’ve seen the same story played out in so

many other films with better acting.

Unless the novelty of its historical significance sounds super

intriguing to you because you’re OCD about film lists like me, this one

warrants a pass.

Arbitrary

Rating: 4/10.