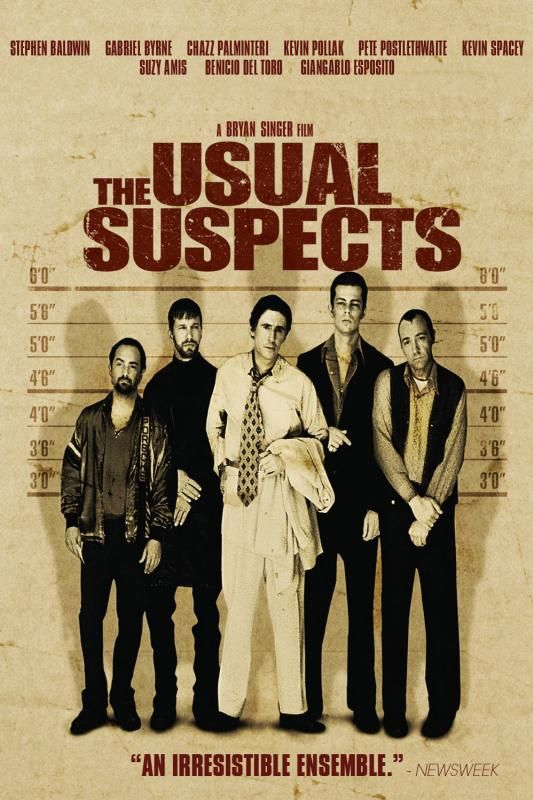

The

Usual Suspects

1995

Director: Bryan Singer

Starring: Gabriel Byrne, Chazz

Palminteri, Kevin Spacey, Stephen Baldwin, Kevin Pollak

Right

around the fifteen year mark is when a film’s worth is most tested. Has it been remembered? Do people still watch it? Do people still talk about it? No matter how much money it made, no matter

how many awards it won, if, fifteen years later, it has been forgotten, the

worth of the film is made clear.

The

fact that we’re still watching The Usual Suspects, more so than

when it first came out, goes to show that it is just a crazy awesome film.

Customs

Agent Kujan (Palminteri) is investigating an explosion at a Los Angeles dock,

and there is only one witness, the crippled con man Verbal Kint (Spacey). Kint’s testimony to Kujan has him telling the

agent about the criminal gang run by Dean Keaton (Byrne) getting mixed up with

the mysterious and deadly evil criminal mastermind Keyser Soze. Soze ordered the gang to take over a boat at

the dock, but soon, Kint and Kujan start to realize that things aren’t adding

up. Just who is Keyser Soze, and why did

he bring these men together?

This

is quite possibly the ultimate neo-noir.

It has so many thick, rich elements of classic film noir, just updated

to appeal to the modern film viewer. The

plot, for one, has all the great elements of the best noirs of the 1940s. The story is convoluted, with twists and

turns and more characters than you can shake a stick at. Hello!

Have you ever tried to make sense of a plot from a Raymond Chandler

film? Same thing! Additional criminals are introduced who enter

then exit, random cops show up but you don’t really know who they are… it’s all

one big thick soup of a story. Sure

makes for one satisfying meal, especially when, after what has to be about my

eighth time of really paying attention to the film when watching, the story suddenly

made sense.

Apart

from the plot, which is beyond gripping (I caught myself holding my breath at

least five times when I rewatched it, and believe me, I know what happens by

now!), the film borrows additional elements of film noir, making it an

automatic love for Siobhan, because Siobhan really can’t get enough of film

noir. The use of the flashback is such a

standard in noir: the flawed hero relating his tale of crime is classic. In The Usual Suspects, not only are

there flashbacks, but there are flashbacks within flashbacks, always relating

back to the present. Moreover, The

Usual Suspects uses voiceover with the flashback. By making the voiceover Kint’s conversation

with Kujan, Singer manages to slip the voiceover past modern filmgoers who may

consider the technique too dated. Yet it

is there nonetheless. It absolutely

reeks of Walter Neff’s confession in Double Indemnity, or Philip

Marlowe’s story to the cops in Murder, My Sweet.

This

is such a macho film. There’s only one

female character and she is incredibly minor.

Edie Fineran is Dean Keaton’s girlfriend, and supposedly the reason that

he’s trying to go straight. While The

Usual Suspects is unlike a noir in that there is no femme fatale to

speak of, I will say that it is similar to a noir in that characters speak of

love without really feeling it. Often

the femme fatale and the hero have a few conversations about loving each other,

but you know that they don’t really mean it.

The hero is attracted to the femme fatale, but he doesn’t love her. He might be obsessed or fascinated, but it is

not love. While Keaton keeps on

protesting that he loves Edie, no one around him really believes him, and given

how easily he seems to desert her, even after she tells him that she loves him,

you doubt that this relationship is as meaningful as he claims it to be. When Edie’s life is threatened in order to

coerce Keaton into working for Soze, Keaton is coerced, but I doubt it was

because of Edie. Keaton would have been

more frightened of a criminal capable of demonstrating such power than he would

be of his random lawyer girlfriend getting taken out.

Because

the film was made prior to the huge computer explosion of the late nineties,

the sets maintain a timeless quality to them due to the lack of dated

technology. There is one instance of a

comically large cell phone, but other than that, the police offices seem not so

much accurate as ripped straight from the page of a hard-boiled crime

drama. Smoking fills the movie; I can’t

count the number of times characters light up.

You don’t see that in modern movies, but it fills the classic film

noirs.

Singer’s

direction is, quite frankly, staggering.

It took a director of uncommon confidence to take on this picture as his

first major studio-produced film. Singer

had one full-length credit to his name, but it was a small film from a no name

studio on a small budget. I’m impressed

that producers would agree to back the film; it goes to show that when

Hollywood takes risks, it can still produce phenomenal films. Singer delights in framing his criminal gang

in interesting settings, often showing them standing all in the same frame,

more often than not using deep focus to put them all into stark clarity.

The

names in the film are fantastic. Names

in film noir often hold substantial meaning; this film is no exception. Take Verbal Kint. The nickname ‘Verbal’ is rather brazenly

significant, he being the one who is telling the story and narrating the film; his

nickname hints at his personality. He is

a talker, a yarn-spinner, a storyteller.

Additionally, consider the last name ‘Kint.’ It’s related to the German word “kinder,”

meaning “child.” Verbal Kint is often

treated as a child, told to stay behind, told he is not ready to deal with the

real dangers of the rest of the gang. He

is small and capable of being manipulated.

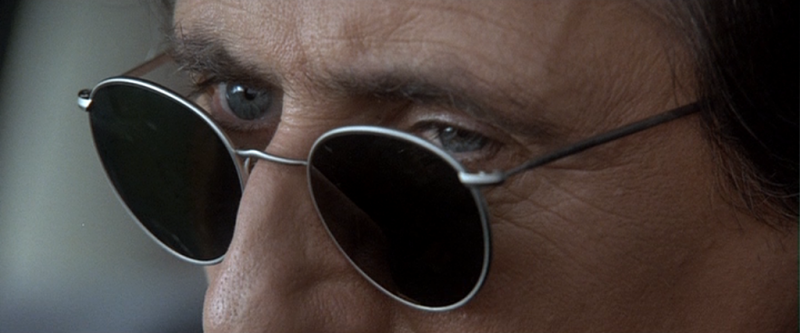

Keyser Soze, the terrifying unknown criminal gangster, has a first name

that sounds just like “Kaiser” or emperor.

He is a man who is in control, who is calling the shots, who is pulling

the strings. Apart from the meaning of

the names, listen to them: Verbal Kint, Keyser Soze, Dean Keaton, Kobayashi,

Fenster, McManus, Hockney, Agent Kujan.

These are highly unusual names, and they all have a hard edge to

them. Listen to the numerous “K” sounds

and “T” sounds. Hard, flinty,

steel-edged names these are. They paint

the characters as beyond reality somehow.

There are no Jones’ or Richardsons’ or Smiths’. They are most certainly characters, larger

than life.

The

Usual Suspects

floored me when I first watched it as a high school student in the spring of

1996, and it continues to impress me today.

It’s so gratifying to have a film that I loved when I was young continue

to enthrall me as a much more experienced film-going adult. I really don’t think that thrillers get any

better than this. It’s so flinty, so

gritty, so perfectly orchestrated, so beautifully executed. I flat out love this movie. Love love love. It’s interesting, it’s thought-provoking, it

tells a gripping story, performances are all in tune – it’s a big, big

wow. And it doesn’t get old. It doesn’t lose its potency with repeated

viewings; if anything, it gets better as it ages. I love this film. Easily in my top ten favorite films of all

time.

Arbitrary

rating: A perfect 10/10.