|

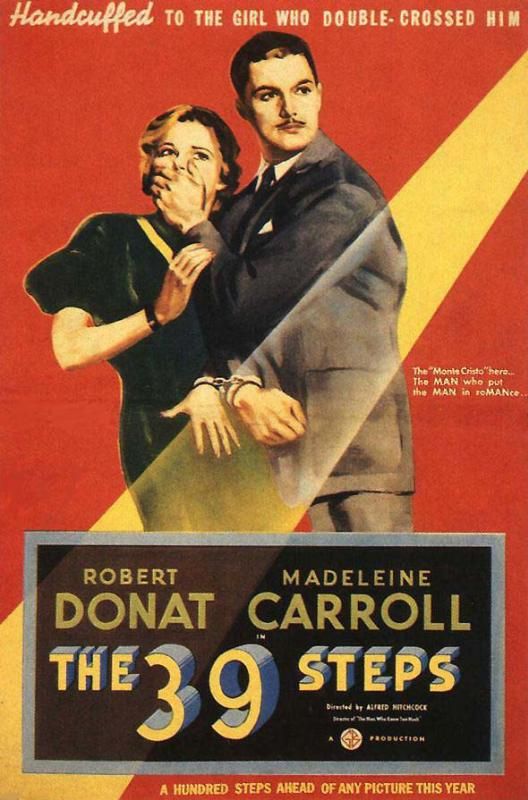

| This was clearly an early poster - notice the lack of advertising for Hitchcock's name. |

The

39 Steps

1935

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Starring: Robert Donnat, Madeleine

Carroll

Alfred

Hitchcock is known as the Master of Suspense, everyone knows that. But what does that mean for a modern viewer

delving into his works? It means that in

a film from 1935, only seven years after talkies hit Hollywood, Hitchcock

produced a truly riveting, suspenseful film that nonetheless contains a sense

of fun comedy as well. That is, classic

Hitchcock.

Our

main character is Hannay (Donat), a Canadian vacationing in England, who goes

out to the music hall one night. A

gunshot rings out through the crowded hall.

In the mad rush out, a mysterious, beautiful woman with an accent asks

him to take her home. She’s a spy, and

when she is murdered in his apartment in the middle of the night, he is blamed

for her murder. He takes on her mission

for the good of England while trying to evade both enemy spies and omnipresent

policemen. What emerges is a mad chase

from London to Scotland and back again, during the course of which he falls in

with cool blonde Pamela (Carroll) who makes things infinitely more difficult.

The

39 Steps

is first and foremost a suspense film, and it’s very well done in this

regard. Hitchcock is clever in how he

ratchets up the tension throughout the film.

In the first half, when Hannay is running to Scotland, the sense of him

being pursued is derived from the major forms of mass communication, mostly the

newspaper. Hannay is constantly trying

to evade newspapers. At first, some

silly lingerie salesmen he shares a train compartment with are nattering about

the murder of the lady spy because they have read it in the paper. Do they suspect him? Suddenly their silliness seems menacing. Hannay escapes to a country croft in

Scotland, but the crofter takes the paper, and he worries again; will they turn

him in? Friends become foes, and police

are always nipping at Hannay’s heels.

There are more close scrapes than you can shake a stick at. It’s a tremendously suspenseful film; not,

perhaps, in the modern cinematic sense, but for a film from the 1930s, it’s

absolutely crackerjack.

The

39 Steps

is also significant in establishing so many traits we associate with

Hitchcock. It’s the first time Hitchcock

fully delved into a story about “The Wrong Man,” a theme he returned to again

and again in his later works. Hannay has

to be clever in order to fight against his unjust persecution. We also have the police as enemies, not as

friends, another major Hitchcockian thematic element. This is played out so fully in The 39 Steps

that you’ll worry far less about the bad guys catching Hannay than the cops

catching Hannay. Hitchcock even gives us

cops flat out lying to Hannay, pretending to believe his story of innocence

then turning around and arresting him.

While the police are not evil in the traditional sense, they clearly

cannot be trusted either. The plot

device that drives the film – seeking out “the 39 steps” because it’s some

impressive spy secret that’s necessary to save England – is a huge MacGuffin. It hardly matters by the end of the film what

“the 39 steps” are; all that matters is that it caused our hero to go on the

run. We even have our blonde female,

cold, a little cruel and a little sexy all at once. I know Hitchcock made a fairly large number

of films before this one, and I’ve seen some of them, but in my rather

uneducated opinion, this is the first Hitchcock movie that is thoroughly and

completely Hitchcockian in nature. It’s

the first time he fully realized what he was all about in terms of story,

devices, cinematography, and dialogue.

In fact, an argument could be made that North by Northwest, when

you boil it down, is essentially a remake of The 39 Steps but with a

bigger budget and better technology.

This is not a knock at North by Northwest, not at all, but

the same ideas that course through its veins are here in The 39 Steps as well.

Hitchcock

was always an innovator, but he concealed it by producing films with mass

market appeal. Throughout his career,

however, he would always dabble with the experimental, finding ways to make his

films using alternate techniques. The

39 Steps is a classic example of this.

Sound was still relatively new, so there is no traditional music

soundtrack in The 39 Steps, but Hitchcock is smart in his use of sound

effects. Just after our mysterious lady

spy has been killed, the phone rings.

There is no swelling of violins in the background (Bernard Herrmann

would come later), but it’s not needed, not with the incessant ringing of the

phone. The ring takes on a sinister

sound as we start to believe it’s the bad guys come to finish off Hannay as

well. When we later see the mysterious

spy’s face superimposed over a shot of the men we think are after her, again we

have Hitchcock playing around with film techniques. Furthermore, there is definitely a play of light

and shadow, perhaps from the influence of German Expressionism, that later

turned into the films from Hitchcock’s oeuvre that are most definitely films

noir.

There

is a sly sense of sexiness that makes The 39 Steps still feel juicy

today. The film was made in England so

there was no Hays Code, but Hitchcock would have still had to play by its rules

in order to get distribution in the States.

That being said, like so many films of the time, Hitchcock found a way

around its strictures to get a little racy.

There are the obvious aforementioned lingerie salesmen who unblushingly

produce undergarments from their briefcase, right before they start telling

dirty limericks. A priest glances a

little too long at said some lingerie.

Hannay has to pretend to be having an illicit affair in order to sneak

out of his flat, and later, throws the police off his track by making out with

Pamela by means of an introduction. The

country crofter who gives Hannay a bed immediately suspects that he is making

eyes at his young pretty wife. And

lastly, much of Hannay and Pamela’s interaction comes with the two of them

being literally handcuffed to each other, so the sly, tongue-in-cheek

suggestions as to how they spent the night together become a bit salacious

(watch how she takes her stockings off, then go get a glass of ice water),

despite the fact that nothing is shown.

It’s all about hinting at all the sexuality without really seeing

anything.

I

love the chemistry between Madeleine Carroll, the cool blonde, and Robert

Donnat. Pamela wholly believes that

Hannay is a murderer, and when she winds up handcuffed to him, things get

interesting. It’s at this point that the

picture turns from a nonstop thrill ride to a romance under unlikely

circumstances. The formula of a

bickering pair turned romantic pair is one of which I will never tire when done

well, and Hitchcock does it well. A

particular favorite scene of mine is when Donnat, tired of trying to convince

her of his innocence, starts to tell Carroll the tall tales of his “life as a

murderer.” He rattles it off with such

an exasperated coolness that she starts giggling. Who wouldn’t?

There

is a delicious sense of a full-circle in this film with Hannay’s game of cat

and mouse taking him from a music hall in London to the moors of Scotland, then

back to a crowded hall in London. It

gives a sense of completeness that is very satisfying. Overall, The 39 Steps is a wonderful romantic

romp, a suspenseful thriller, and a great adventure. For me, I have a soft spot for it because I

saw it in my first month of watching films from the 1001 Movies list,

and it truly impressed me. I still

remember watching it for the first time and getting completely caught up in the

suspenseful adventure, literally dropping my jaw on more than one

occasion. It’s a little primitive, but

no more so than any other film from the thirties, and more advanced than most

of its counterparts. Most of all,

though, this is a fully realized Hitchcock film.

Arbitrary

Rating: 9/10. A sentimental favorite.