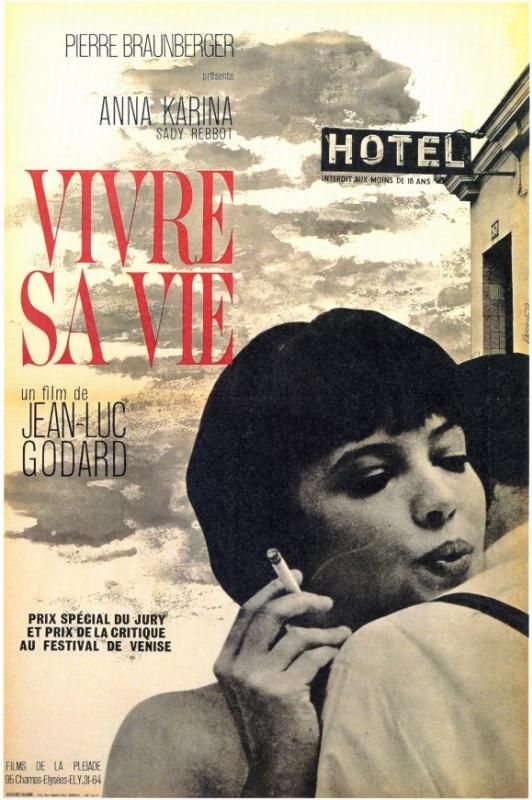

My

Life to Live (Vivre Sa Vie)

1962

Director: Jean-Luc Godard

Starring: Anna Karina, Sady Rebbot

My

Life to Live

is an early yet wholly realized entry by Godard in the French New Wave

style. I’m not really a fan of the

French New Wave, and I’m definitely not really a fan of Godard, but I find My

Life to Live rather captivating.

It’s Godard before Godard went off the cinematic deep end, and honestly,

if I had to recommend a film to start Godard’s repertoire with, it would be

this one.

Told

in twelve distinct tableaux, each with their own oddly antiquated title card, My

Life to Live is about the young Parisian woman Nana, an aspiring

actress. Nana (Karina) opens the film by

breaking up with her boyfriend, Paul, but he was helping to support her; her

job at a record store doesn’t pay her well enough, and on her own, she soon

descends into prostitution. A run-in

with an old friend who is also a prostitute introduces her to a pimp Raoul

(Rebbot) and she all too easily seems to adjust to “The Life” (part of a play

on the title of the film). In parts of

certain episodes, she acts happy, but it doesn’t take a stretch of the imagination

to realize she isn’t, and Nana’s doomed existence seems a matter of fact.

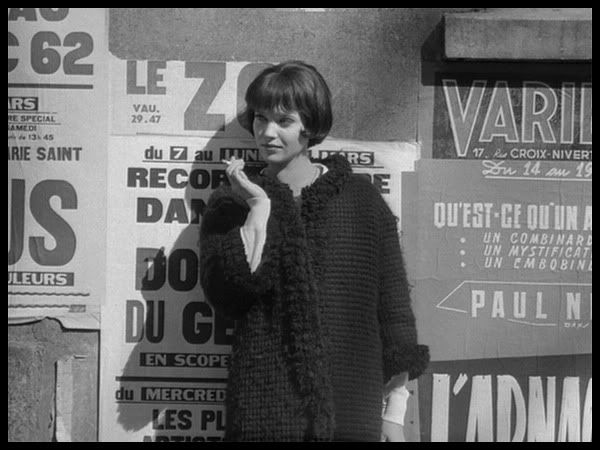

Godard

was married to Karina when he filmed My Life to Live, and I think it

shows. The way the camera moves around

Nana, chronicling her life through her viewpoint, and yet always somehow

exhibiting Karina’s almost alien-esque beauty is a sign of this. We get so many shots of her eyes, her mouth,

her smile, her dark hair, her lithe frame, her profile. Karina is luminous in this film, and I think

I’m a little entranced by her here. The

camera is too, as it slowly pans back and forth, watching her as she talks to

her pimp, or slowly zooms in and out on her face as she is talking to a

friend.

Speaking

of the camera, there is an odd lack of faces in this film. Take the opening scene where Nana breaks up

with Paul. The two are sitting at the

counter in a café, but they are shot from behind. We can see Nana’s face reflected in the

mirror behind the counter only slightly, but we have no such reflection of

Paul. Nana’s head moves, we know she is

speaking, but the voice that answers her is almost disembodied. Other characters in the film get similar

treatment. Nana listens to her friend

recount how she started in prostitution, but it is about Nana listening and not

the friend, as we rarely see her during this conversation. Godard foregoes two-shots in favor of clearly

focusing on Karina as much as possible.

When we do occasionally see the full face of another character, it is

brief and almost surprising because we have gotten used to the backs of

heads.

Significantly,

the one character who gets the most face time in the film is an “extra,” French

philosopher Brice Parain. Nana strikes

up a conversation with him in a café when she is well-ensconced in her career

of prostitution, but she quickly moves from trying to hit on him to simply

discussing life with him. In this

conversation, we focus far more on Parain, who talks about thought and life and

love and age, with Nana only occasionally joining in. Because the camera focuses so much on Parain,

perhaps this is saying that this man, this conversation, is one of the few

moments in her life where Nana can focus on something other than herself. Perhaps the camera focuses so squarely on

Nana, to the extent of even blocking out other characters, in the rest of the

film to show Nana’s self-centered nature.

But here, in this conversation, she is entirely present and paying

attention to what someone else has to say.

It’s a significant moment for both her and the film, as it precipitates a

change in her approach to prostitution.

After this conversation, sad Nana tries to break free from The Life, an

attempt that clearly spells her doom.

The

music is an interesting choice in My Life to Live, and just another

example of Godard’s philosophy that film should be self-aware. There is a beautiful and incredibly sad

sixteen bar theme that was written for the film, but that is the only piece of

soundtrack score we ever hear.

Occasionally it repeats and we hear it for more than a minute or so, but

most of the time it comes in and simply plays the sixteen bars, then stops just

as abruptly as it starts. We expect

more, we want more, but Godard reminds us this is a score and not actually part

of the events taking place on the screen, so why should it extend the length of

the scene? I really hesitate to even

call it a score or soundtrack, but it is a very lovely theme for a film.

Prostitution

is treated with tremendous alienation in My Life to Live, essentially

mirroring how Nana feels about what she’s doing. In the coldest segment of the film, Nana asks

her pimp what “the rules” are regarding rooms, hours, fees, police regulation,

and even abortions. It’s downright clinical,

and through what is easily the shortest of the twelve parts of the film, Nana descends

wholly into her “life.” The sex is

clearly not shown (this is 1962 after all), and there is no glamour. Just as the Paris we see is littered and

cheap, the sex is cold, almost utilitarian.

There is no titillation about Nana’s profession, but neither is there a

sense of yawning depression about her lot.

It’s simply there, a banal, boring fact of Nana’s life.

As

Nana is the clear focal character of the film, it’s odd that although I like

her, I don’t love her, nor do I feel much sympathy for her, and yet that

doesn’t stop me from rooting for her.

Her life descends quickly at the beginning of the film into her

situation, but she is also a bit cold and cruel. When she breaks up with Paul in the opening

scene, she’s downright awful, and it’s a bit disconcerting how quickly she

seems to adjust to prostitution. Is she

likeable? I’m really not sure. And yet, on her side, she is moved to tears

at the cinema by an intense scene from The Passion of Joan of Arc, she is

fascinated with the philosopher, and despite her headstrongness taking her into

the existence it did, she does not deserve her doom. To me, the final two “chapters” of the film

make up its emotional crux. Nana starts

to awaken from her existential stupor, but just as she does, she is stricken

down by the trappings around her, bound to the life she has unwittingly buried

herself in. It’s tragic, it really is.

Accessible

in terms of a straightforward narrative yet inventive in terms of film

philosophy without being absolutely insane, My Life to Live is a good

starting place for Godard.

Arbitrary

Rating: 8/10