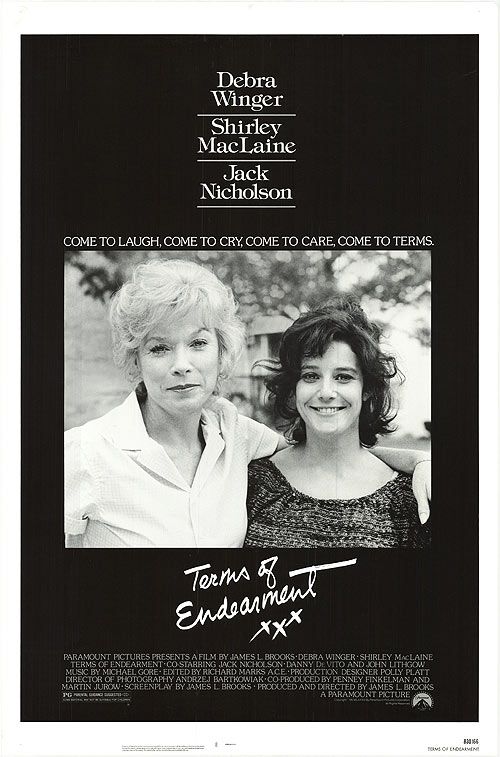

Terms

of Endearment

1983

Director: James L. Brooks

Starring: Shirley Maclaine, Debra

Winger, Jeff Daniels, Jack Nicholson

I

don’t think it’s possible to be a consumer of popular culture and not have some

concept of what Terms of Endearment is all about. The driving on the beach scene is the most

famous cinematic moment from the film, but everyone seems to know the basics of

the plot and how it ends. So really, I

shan’t be terribly careful about keeping the ending a secret; I don’t consider

it a spoiler in the least (it certainly wasn’t for me). You have now been warned.

Aurora

Greenway (Maclaine) was widowed as a young mother. Living in Houston in a very nice house, she

is anxious and overprotective of her young daughter Emma (Winger). When Emma grows up, Aurora disapproves of her

husband, Flap Horton (Daniels), a young English professor. Emma and Flap have children and move away, but

Emma and Aurora maintain their relationship through long distance phone calls. Eventually, Aurora starts to take up with the

next door neighbor, ex-astronaut Garrett Breedlove (Nicholson), while Flap and

Emma both engage in extramarital affairs of their own. And then Emma’s doctor discovers a couple of

lumps in Emma’s armpit, and cue the hospital sequences.

The

basic plot outline of “mother-daughter relationship through the years

culminating in untimely death of daughter” sounds exactly like the kind of

melodramatic claptrap I desperately avoid.

But Terms of Endearment manages to transcend its Lifetime:

Television For Women trappings for two reasons.

One: the movie is based on a novel by Larry McMurtry, he whose previous

written work lead to The Last Picture Show, Hud,

and most recently, Brokeback Mountain. Two:

James L. Brooks, he who helped unleash The

Simpsons onto an unwitting populace.

The

way I see it, were it not for these two men (men in a women’s picture!), I

would be writing a much angrier review right now. Both of them supply a very distinct and

necessary counterweight to the saccharine story this film could easily devolve

into.

For

McMurtry’s part, he writes tales that have great and profound emotional

resonance to them, but with a very flinty edge.

He is not scared to thrust the knife in the gut when he must. Consider the cow slaughter sequence in Hud,

and the bit with the tire iron in Brokeback Mountain. While there is no similar violence in this

film, there is a similar dash of cold cruelty every now and then, a fact which

offsets the story just when it was feeling too sweet. Perhaps it is in the way that Emma so

blithely cheats on her husband, or how her oldest son Tommy still pulls away

from her on her deathbed, or how Aurora flatly tells her daughter she won’t be

attending her wedding. These moments,

and their repercussions, help keep the film moving along a solid

trajectory. In a Lifetime Movie of the

Week, the last action in particular would be followed by scene upon scene of

histrionic wailing and arguing. Not so

in Terms

of Endearment. Emma is upset

with her mother, but doesn’t yell. She

just walks out of the room. Although

Aurora misses the wedding, the two are back speaking to one another in a matter

of weeks. This is a very different tone

from what I was expecting.

In

terms of James L. Brooks, he takes these life events and injects a heaping dose

of what has now become his trademark gentle comedy. I don’t think anyone does gentle comedy like

Brooks. As Good As It Gets and Spanglish,

two of his more recent directorial films, had that humor in spades, and I

confess, I really like both of those movies.

Terms of Endearment opens with a shot of baby Emma sleeping in

her crib. Aurora peeks her head in the

room while her husband yells at her from the next room to leave her alone. Aurora, however, is insistent that because

her daughter is sleeping silently, it means her daughter has died, and is not

content until she wakes Emma and Emma starts to cry. At this point, Aurora leaves the room

happy. That scene immediately made me

laugh, while remembering that this, after all, is James L. Brooks. So many of these moments throughout the film

make you laugh or giggle while something life-changing is happening.

Both

Maclaine and Nicholson won Oscars for their roles in this film. Both are very good, but not

career-defining. For his part, this

feels like the first film Nicholson made that was the Nicholson we have today:

that older man with the creepy smile grabbing life by the ping pongs. In 1983, Nicholson was probably playing older

than he actually was, and he gained weight to make himself seem more like a

former superstar gone to promiscuous seed.

At the time, it was probably a new Jack.

Now, it’s lost its novelty; it’s the Jack who keeps making movies like The

Bucket List. Hey, at least this

flick is pretty good.

The

central relationship that drives the film is that of mother and daughter. While not a perfect match, I kept being

reminded of Gilmore Girls (only one

of my favorite TV shows ever).

Especially in the second half of the film, Aurora and Emma talk to one

another more as friends than as mother and daughter, which is probably which I

kept on thinking of Lorelai and Rory (it also didn’t hurt that Gilmore Girls references Terms

of Endearment a couple times). I

liked seeing that. But what confused me

was how the movie, the entry in 1001 Movies, and pretty much every other

review I read of this film talked about how Aurora and Emma have a strained

relationship. I saw no such strain. When Aurora says to Emma that they fight all

the time, Emma is surprised. “That’s

just how you see it.” I can’t help but

agree with Emma on this one. I honestly

do not get how this is a tempestuous relationship. I saw a mother and daughter who clearly love

each other, are very close, and occasionally piss each other off but never for

long. How on earth is that a strained

relationship?

Despite

using too much soft-focus (waaaaaaaaaaaaaay too much soft-focus) and dragging every now and again, there was enough

bite in the story to keep it moving forward without getting bogged down. Sappy clichés can’t quite help from creeping

in every now and then, but the film does its best to beat them back. And although it has certainly aged and dated

itself (really, who hears they have two lumps in their armpits and doesn’t

immediately want to get it checked out for cancer?!?), it’s still a nice little

story. A little predictable and not

exactly challenging, but every movie cannot – and should not – be a surrealist

experiment.

Arbitrary

Rating: 7.5/10.