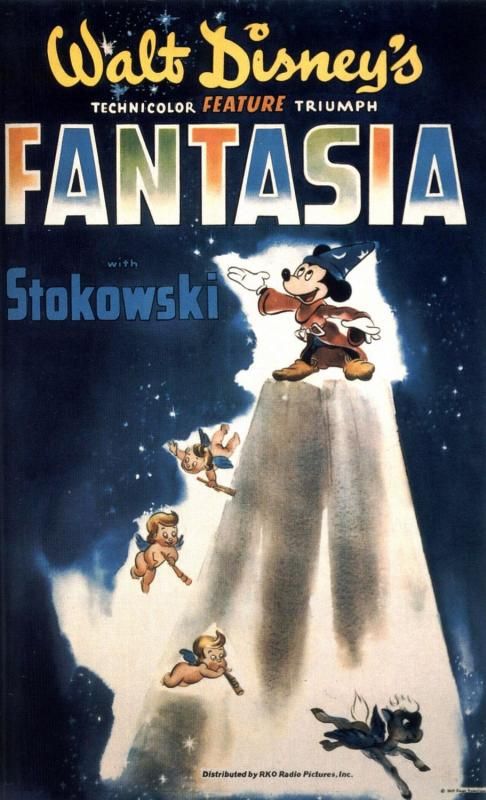

Fantasia

1940

Producer: Walt Disney

Starring: Leopold Stokowski, Disney

animators

Fantasia is wholly unlike any other

movie out there, excepting, of course, Fantasia 2000. Its entire premise is completely different

from a typical film. It is about

music. Any sort of narrative in the film

is derived entirely from the music, and not the other way around. Any sort of image in the film is derived from

the music, not the other way around. The

music was not implemented after the fact, meant to accompany what had already

been committed to screen; the music came first, and the screen came

second. This is avant-garde filmmaking,

but made by Walt Disney, of all people.

We tend not to think of Fantasia as experimental because it

comes with the Disney tag, but you better believe this is out there in terms of

basic structural design.

Because

this is a movie entirely about music, and classical music no less, most of my

review is going to focus on just that. I

am a classical musician. I have decades

of experience performing in groups, and I listen almost exclusively to

classical music of one type or another.

In

case you want to skip to the punchline, I’ll say this right now: I love Fantasia. Why?

Because it’s entirely and exclusively about the music that I adore. How awesome is that?

There

are seven distinct pieces of music in Fantasia, and given that the entire

film is “about” them, in a sense, I am going to discuss each one. We have J.S. Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D

Minor (which I’ve played), selections from Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker ballet

(which I’ve played), Dukas’ The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, Stravinsky’s Rite of

Spring, Beethoven’s entire Symphony No. 6 (played it), Ponchielli’s Dance of

the Hours, and Mussorgsky’s Night on Bald Mountain (played it) smashed together

with Schubert’s Ave Maria. I’m going to

discuss each one because you have to consider this film. These distinct seven pieces were chosen from

all of classical music to BE Fantasia. They were not picked because they would make

a good soundtrack accompaniment to whatever action Disney had already put to

film; they were chosen FIRST, and THEN Disney created images to match.

We

start with Bach’s Toccata and Fugue.

It’s the only baroque selection of music in the film, but it’s fitting

to open the piece. Baroque was one of

the earliest styles of classical music.

In my head, I call it a very “up and down” style of classical music, in

that the focus is mostly on music theory and technique, and not on evocation of

emotion or even imagery. Now, I’m sure

some will argue that last point, but really, when you compare baroque to

romanticism, there IS no comparison about which style is more emotive. Given that, of all the styles of music, I

find baroque to be LEAST emotional, I also think it’s incredibly fitting that

in Fantasia,

this is the one piece that is the most abstract in terms of the animation. There are no recognizable characters, let

alone anything resembling a story. It is

purely impressionistic, which is dead on, spot on perfect for a baroque

piece. The picking of Bach’s Toccata and

Fugue is a fine representation of baroque music, and one that audiences at the

time would have been familiar with. The

iconic work had already been used in horror films (starting with The

Black Cat in 1934).

The

next selections are pieces from Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker ballet. Now, in order to explain why this is an

interesting selection, I have to give you some history about the Nutcracker

ballet. Nowadays, everyone is familiar

with the Nutcracker. It’s a Christmas

staple, performed in every major city in December, and in many more small towns

as well. You cannot get through a

Christmas season without the music from the Nutcracker being used in multiple

television commercials or piped endlessly through shopping malls.

In

1940, when Fantasia was made, this was not the case.

The

tradition of annually performing The Nutcracker at Christmas is a wholly

American one. When it originally premiered

in Russia in the 1890s, the ballet was not successful. It languished for about half a century, until

it gradually started being performed again in the 1940s. It wasn’t until the 1950s that it got its big

break. George Balanchine started

performing The Nutcracker with the New York City ballet in the mid-1950s. In 1958, CBS television approached him about

airing a live broadcast of the show. It

was a huge hit for CBS, and they started airing it annually at Christmas. Thus was born the completely American

tradition of staging the Nutcracker ballet at Christmastime.

Having

said all of that, let’s go back to Fantasia. How Disney animators picked this particular

piece, given that it held little cultural touchstone appeal for society at the

time, is beyond my comprehension. Surely

Swan Lake would have been a more

famous piece of Tchaikovsky’s at the time, or even his Symphony No. 5. But no, they picked The Nutcracker, and I’m

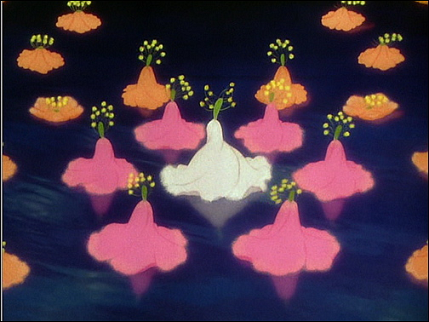

glad they did. What we have, therefore,

is an interpretation of Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker that is wholly freed from the

story of the ballet. It is focused

entirely on the MUSIC. While there isn’t

a story associated with the Nutcracker segment in Fantasia, it is not

nearly as impressionistic as the first segment, containing distinct and

recognizable images. The images are

essentially scenes from nature.

I

adore the Nutcracker ballet. I have

either been in it or been to see it every year since I was three. I know the music by heart. And I really love this segment of Fantasia. I love the alternate interpretation of the

pieces, and they are lovely interpretations.

Tchaikovsky,

in terms of musical style, falls squarely within the Romantic era of classical

music, characterized by highly emotional, even melodramatic musical gestures

and pieces. Personally, I love

Tchaikovsky – he has such a distinctive compositional style, I could easily

pick a piece of his out of a lineup – and I think it’s entirely fitting that he

be included in Fantasia.

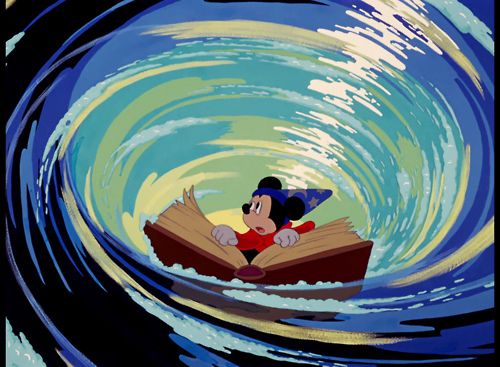

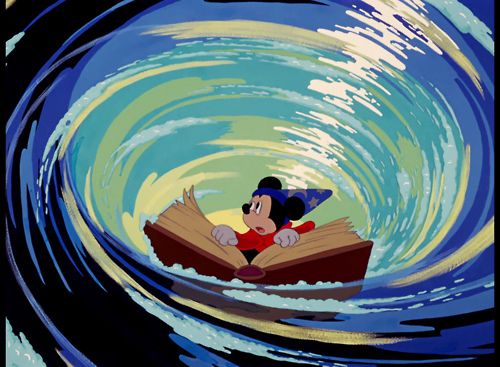

The

next segment is the most iconic one in Fantasia, Dukas’ Sorcerer’s

Apprentice. This is a terrific piece of

classical music, telling a very definite story, and like Tchaikovsky, falling

squarely in the Romantic era. I like the

animation in this section, and it has, in large part, defined the film as a

whole. How many times have you seen it

parodied on other animated shows like The

Simpsons? From a music standpoint, I

think this is an absolutely stellar interpretation of the piece. There is a moment – a trumpet fanfare – at

the climax of the piece that just makes the entire recording for me. Most recordings of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice

gloss over this very brief fanfare, but Stokowski ever so slightly slows down

the orchestra for this moment. It makes

the entire thing for me. It sends chills

up down the back of my neck. I’ll put it

this way – I never listen to any other recording of Sorcerer’s Apprentice than

the one from Fantasia, because I have yet to find a better one.

The

next segment in Fantasia is easily the most courageous musical choice in the

film. Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring is also

the most musically different piece from all the rest in the film. It debuted in 1913, a mere 27 years before Fantasia,

making it the most modern piece in the film as well. It is a glorious work, immensely complicated,

dissonant, and it freely plays with rhythms and time signatures; yet, unlike so

many of its twentieth century progenitors, there is a definite musical theme

and melody. I have never played The Rite

of Spring, but I have been to two live performances of it, and I’ve seen the

score. It’s fiendishly difficult. The entire Rite of Spring is more than half

an hour long; the Rite of Spring that’s in Fantasia is truncated and

reorganized. I’m alright with that; I

understand that, in order to create a film, some editing needed to take

place.

The

animation accompanying it is sometimes cited as the most exciting segment in Fantasia. It tells of the evolution of the universe, of

our planet, of early life, then of the dinosaurs – the dinosaur segment usually

being the bit that people remember. Rite

of Spring was originally composed to represent a primitive, tribal ceremony,

and I think Disney’s reinterpretation works well. While not depicting an actual tribe or actual

people, the idea, the intent is there.

In terms of violence, this is the most aggressive section of the film,

and to me, that makes absolute perfect sense in terms of Stravinsky’s piece. Rite of Spring is a boldly aggressive piece

of music. Seeing volcanoes erupting and

dinosaurs killing one another just makes inherent sense when listening to

something as deliciously dissonant as Stravinsky.

Next

up is the big one. The central rock of Fantasia,

at least to me. Beethoven’s Sixth

Symphony. I love Beethoven. I’m going to repeat that, because it bears

repeating. I love Beethoven

hardcore. He is my favorite

composer. You might think it a bit

cliché to pick Beethoven as your favorite composer, but trust me, this comes

from years of exposure to many composers’ work.

I keep coming back to Beethoven.

I have an intense emotional connection with Beethoven’s work. He is the only composer whose pieces have

moved me to tears. I don’t think there are

any other composers capable of such painful beauty as Beethoven. In his music, I see such loveliness, but

under it, there is often a melancholy air.

His Sixth Symphony typifies this.

I will never get tired of listening to the Sixth. As a symphony as a whole, it’s my favorite. And trust me, I know Beethoven’s

symphonies. The only item on my bucket

list is to either perform live or see performed live all nine of Beethoven’s

symphonies. I’m missing three: the

second, the third, and the fourth. I’ve

either performed or been to see all the others.

Sure, there are individual movements of his other symphonies that I

think are stronger or more emotional than those in the Sixth, but in terms of

the symphony as an entire work, the Sixth is unbeatable. Yes, more than the Ninth. Yes, I love the Ninth. Yes, I still prefer the Sixth. (Perhaps I am slightly biased – I am a

clarinetist, and the clarinet part in the Sixth is just amazing.)

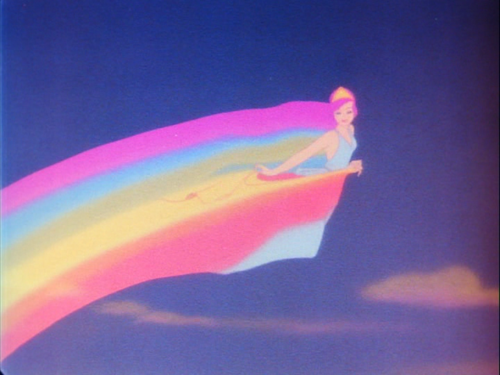

When

I was a young girl, I loved this section of Fantasia because it was

basically a half hour episode of My

Little Pony. Having grown up now, I

find it to be a little immature for my taste.

Basically, I love Beethoven’s Sixth so much that I don’t like seeing

silly little animal creatures being played for laughs in a piece in which I

find so much emotional profundity.

Having said that, though, I have to go back to my original statement –

when I was little, I loved this section.

And isn’t that huge? I mean, this

part of the movie was instrumental (ha! Get it?) in nurturing my love and

adoration of classical music. So what if

there’s a little bit of silliness or commercialism mixed in there? If it can help youngsters of today get into

classical music as well, then I’m okay with it.

Disney certainly got the “pastoral” part of the piece right,

though. I like the bright pastel color

scheme; I think that fits with the piece very well. I just picture something different than

Disney when I hear the Sixth. Not so

many naked cherub butts.

This

is not my favorite recording of the Sixth symphony. I think the second movement is a little too

slow, the third movement not quite jovial enough and lacking in life, and the

final movement a little lacking in grandeur, plus the whole symphony is truncated. In terms of that last point, again, I

understand why it was truncated, this being a feature film after all. I do not argue the right of the editors to

edit. However, I will argue that if you

wanted Beethoven and you wanted pastoral AND you wanted something shorter, why

didn’t you use the first movement of the Seventh symphony? It’s much shorter and just as “romp in the

countryside” as this. Or, for that

matter, the third movement of his violin concerto. Ah well.

In

terms of musical style, there is a bit of argument as to where Beethoven

belongs, so I’ll just tell you where I think he belongs. Beethoven was the crossover composer; he

ended the Classical era in classical music and issued in the Romantic era. If you listen to Beethoven’s First and then

listen to Beethoven’s Ninth, they are worlds apart. His First Symphony is highly derivative of

Mozart, the king of the Classical era.

By Beethoven’s Ninth, he had fundamentally shifted how he wrote music,

using far more emotional motifs and much less emphasis on technique or

precision. In terms of Beethoven’s

career, I firmly place the Sixth Symphony in the Romantic era.

Man,

I love Beethoven.

Ponchielli’s

Dance of the Hours is the penultimate selection in Fantasia. The piece itself very clearly depicts the

passing of the hours of the day, starting in the morning, then having a sleepy

afternoon nap, then a wild evening party.

Dance of the Hours is by no means the only classical music piece to do

this; von Suppe’s Morning, Noon, and Night in Vienna overture follows a similar

structure. But Dance of the Hours is a

great piece, highly evocative of its title, clearly containing distinct

imagery. This is the also the goofiest

of all the segments in Fantasia, what with ostriches in

pointe shoes, fat dancing hippos, and alligators sadly unable to catch said

hippos. To reiterate some of my comments

about the Sixth, I don’t really like this segment NOW, but when I was young, I

loved it. I feel I’ve somewhat outgrown

this particular animation, but I wouldn’t cast it aside. It’s important to have some kiddie appeal –

this is Disney, after all. I also think

this is the funniest of the segments.

Again, I don’t know how much I personally like it, but I do think it’s

important to have some broad comedy in there.

It helps coat the pill of classical music, making it go down much easier

with little ones.

In

terms of musical style, Dance of the Hours is much akin to Tchaikovsky’s work,

being written within about fifteen years of the Nutcracker ballet. As such, it is also firmly Romantic in its

style. Are we noticing a pattern

here? I hope so.

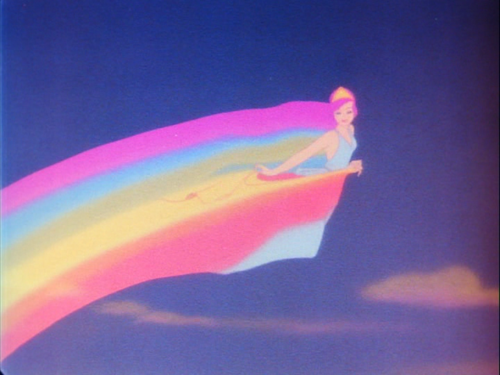

The

final segment is Mussorgsky’s A Night on Bald Mountain mashed up with

Schubert’s Ave Maria. A Night on Bald

Mountain is an effing creepy piece of classical music. Stephen King is said to have seen Fantasia

and been terrified by this particular segment.

I find that those of my high school students who have seen this film

remember this segment the best. It’s a

towering piece of infernal music, incredibly frightening at its core. The animation that accompanies is absolutely

perfect in its ghoulish splendor. There

seems to be a bit of experimentation with animation techniques to achieve the

ghost effects. The dance of death is so

frightening, perhaps one of the most supernaturally frightening scenes that

Disney ever put to film. In terms of the

animation, it’s probably my favorite part of Fantasia.

All

of which makes me sad that Disney basically took a butcher knife to the piece,

picking and choosing what they wanted, and then discarding the ending. Instead of using the actual ending of A Night

on Bald Mountain, which has a definite Ave Maria sacrosanct feel to it, they

feel the need discard most of it and tack on Schubert’s actual Ave Maria, one

of the most sinfully boring pieces of classical music ever. A Night on Bald Mountain has everything

Disney wanted for this final piece. Why

the hell did they have to mess with it, cut it up, and throw in that damn

Schubert piece? That bugs me.

Again,

going back to musical style, both Mussorgsky and Schubert were Romantic era

composers. So we have seven sections of Fantasia,

and of them, one is baroque, one is twentieth-century, and the other five are

Romantic. Personally, the Romantic era

is my favorite era in classical music, so I suppose I shouldn’t complain, and I

can understand from a storytelling point of view why choosing Romantic pieces

was the easiest as many of them already have distinct emotions or even stories

built it, but I highly question their omission of the Classical era. I mean, Mozart is the behemoth of classical

music, and his work does not appear in either Fantasia or its

sequel. What gives? In my opinion, this is a glaring omission

that should never have gotten past the initial discussion of what this movie

would be.

In

many ways, I wish Disney Studios would return to the studio that produced this

film. Today, Disney is synonymous with

Cash Cow, merely existing to sell little girls the Princess Dream and bank off

whatever Pixar produces. But back in 1940,

when Disney produced Fantasia and then Pinocchio,

it was a much different studio. Artistic

experimentation and expression were more important (or, at least, just as

important) than making money. To this

day, Fantasia

remains the single best classical music movie ever made because it is wholly

about the classical music. The classical

music does not take a back seat to any sort of contrived plot line about

struggling musicians or some other nonsense.

The classical music came first, and the images followed. How brave of the studio, how incredible a

film, and how wonderful for someone like me.

It’s the perfect marriage of two of my greatest passions: classical

music and film coming together.

Arbitrary

Rating: 8.5/10. There are moments of

pure perfection, but also moments that are not so perfect. And this is a hugely significant film for me.