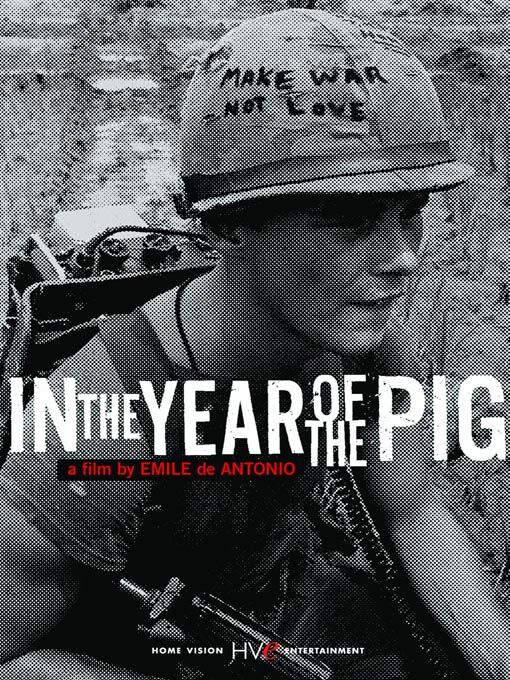

In

the Year of the Pig

1968

Director: Emile de Antonio

Starring: the politicians, soldiers,

and Vietnamese of the sixties

I

was not alive for the Vietnam War, but my parents were. More than that, my father was of draft-able

age during the Vietnam War. I did not

live through these years myself, but my parents have talked at length about

what it was like for them in the late sixties and early seventies. And yet, despite these discussions and two

years of US History classes in high school, the Vietnam War still remains a

political quagmire to me, full of unclear intentions. It’s very easy for me to understand why the

US was split in terms of supporting and protesting this war, but understanding

the war itself is much more complicated.

This

documentary uses footage from various sources – newsreels, shot footage,

photographs, interviews – along with audio of interviews from mainly Western

politicians to track through the history of conflict in Vietnam in the fifties

and sixties. de Antonio starts with an

examination of French involvement in Indochina and from there, discusses how

the various factions came to power in Vietnam and how the US came to be

involved.

In

the Year of the Pig

is a very powerful anti-war documentary, but its potency is increased because

of when it was made – 1968 – and how it was made. de Antonio was ballsy enough to make this

during the war, not after. The Vietnam

War would still persist for several more years.

This was an ongoing war when this film was released. The subject material is not being treated

with 20/20 vision of history looking back on what has happened, this is what

WAS happening. There is an immediacy,

therefore, to In the Year of the Pig that all other films about the Vietnam

War, even the narrative films, lack. Outcome was uncertain. Everything was uncertain.

The

style of the documentary works as well.

What makes the film powerful is the hands-off approach by the

filmmakers. I tend to find that

documentaries where we never see or hear the filmmakers more effective. Perhaps that’s simply a personal preference,

and I’m certainly no expert on documentaries, but messages tend to be stronger

if an audience can discover them for themselves rather than have them spoon-fed

down their throat. But de Antonio’s hand

is all over the film despite his visual and audio absence. He is clever, very clever, with the

editing. For example, he takes an

interview conducted with a nuclear officer on a destroyer who says that their

ship was never attacked by enemy torpedoes and splices it together with a press

conference by a politician who rails about how said ship WAS attacked by

torpedoes. Not much later, we hear a

politician make a statement that the prisoners the US have taken are being

treated fairly while we watch footage of a Vietnamese man being beaten by US

soldiers.

This

sort of careful and deliberate editing is hardly objective, and that’s the

point. This is an incredibly subjective

documentary that does not attempt to present both sides of the issue fairly and

without comment. Oh no, de Antonio is

commenting most vociferously (all from offscreen, of course) in order to combat

what he presents as equally subjective messages coming from the US

politicians. It’s as if de Antonio is

showing us the “other side” of the story, the one the government “doesn’t want

you to see.” At the very least,

regardless of your personal feelings about politics, de Antonio should make you

question the veracity of the message that came out of the politicians’

mouths. He makes a decently strong point

about the disconnect between what was said back in America and what was

happening on the ground in Vietnam.

A

poetic and rather sad speech by a member of the clergy who had visited Vietnam

on several occasions is part of what closes the film. It’s a plaintive cry for peace. This is intercut with journalists describing,

a bit coldly but heck, they’re journalists, the power they had witnessed of the

North Vietnamese. Although de Antonio

certainly didn’t know exactly how the Vietnam War would end, the end of the

film has a frightening sort of foresight, one that seems to suggest at what

would eventually happen.

If

anything, In the Year of the Pig, although not the most gripping film

ever made, is a way to attempt to immerse oneself in the era in which it was made. By watching a product of the sixties about

the seminal event from the sixties, we have, in essence, an important

historical artifact. Just as watching

all the films from the 1930s that deal with the Great Depression in some way

helped me to understand the implications of that event in a way no history

class ever could, In the Year of the Pig gives me an artistic way to experience

the incredibly muddied politics of the Vietnam War.

Arbitrary

Rating: 7.5/10