Internet has been incredibly spotty and out for the past few days. We need a new modem, but can't get one until Monday. Ugh. Also - who gets a cold in June? Apparently I do. What the hell, body?

A

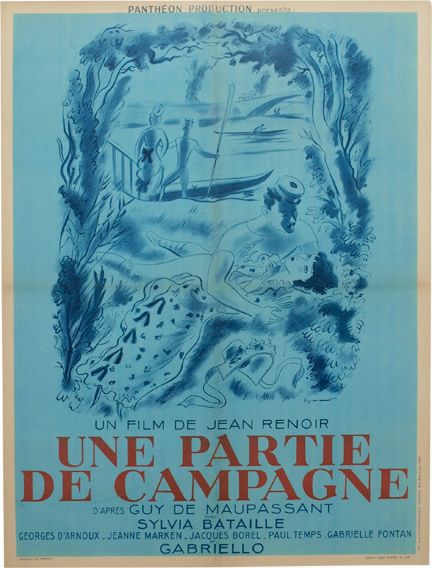

Day in the Country

1936

Director: Jean Renoir

Starring: Sylvia Bataille, Georges

D’Arnoux, Jacques B. Brunius, Jane Marken

What

is it about Jean Renoir that he can, even with an unfinished film, so deftly

strike at such powerful, soulful poignancies?

A Day in the Country was abandoned by Renoir and is clearly

incomplete, but he manages to still stir feelings of passion and tragedy in a

simple story.

Henriette

(Bataille), a young shopkeeper’s daughter from Paris, accompanies her parents,

grandmother, and, we learn, her future husband Anatole, for a day in the

countryside. Her family picnics under a

cherry tree where they are spied upon by Rodolphe (Brunius) and Henri

(D’Arnoux), two young boaters. Rodolphe

and his crazy moustache sets his sights on seducing Henriette and her mother

(Marken) by luring them away from the others, and Henri, rolling his eyes at

his friend’s antics, comes along for the ride.

But soon Henri and Henriette cannot deny their attraction for one

another, and a boat ride alone leads to romance. These are only moments of happiness, however,

as Fate has other plans for Henri and Henriette.

It’s

remarkable how in a brief, unfinished film of only 40 minutes, Renoir manages

to make me care far more about his leading couple than any romantic comedy from

the last 15 years has done. Undoubtedly

Renoir makes me care so much because of who he surrounds Henri and Henriette

with; namely, some of the silliest characters to ever grace the screen. Everyone except these two are essentially

cartoon characters. Henriette’s father

and Anatole look like Laurel and Hardy, as dad is a blundering buffoon and

Anatole is a pasty incompetent.

Henriette’s mother isn’t any better, fluttering around and having fits

and flirting with anything that crosses her path. Rodolphe’s personality is made infinitely

clear by the fact that he wears a mask to protect his moustache while he’s

eating. After that, it’s no wonder that

all he can think of is having a “bit of fun” with Henriette.

With

so much cartoon silliness around her, Henriette immediately stands apart from

her family. Her wide-eyed joy with which

she greets the country is different than her mother’s simpering. She is drinking the country in, overwhelmed

at its juxtaposition with the urban life she knows. The happiness she exudes while playing on the

swings is not the same as her mother’s fussy giggling, this much is clear. The same goes for Henri. I get the feeling he’s only friends with

Rodolphe because it’s convenient, and not because he likes him at all. Henri listens to his friend talk about

conquests and ignores it. When Rodolphe

suggests Henri distract Henriette’s mother so he, Rodolphe, can make time with

Henriette, Henri goes along with it more to shut him up than anything

else. Henri is serious, the antithesis

of the superficiality of everyone around him.

But as soon as we see Henri and Henriette side by side, it is clear that

they belong together. They have to be

together. It’s utterly necessary.

And

herein lies the tragedy of the film. We

learn right from the very beginning of the film that Henriette will eventually

marry Anatole. That’s important, because

there is a sense of sadness right from the beginning, knowing that her fate is

not with Henri. When Anatole is quickly

shown to be a useless clown, the happiness that we see in Henriette’s face

takes on a different tone. Rather than

being happy for her for having this day in the country, I felt immensely sad

that this was a one-off occasion, a day of bliss not likely to be repeated. With a few brief scenes of Anatole being

idiotic, it is all too clear what Henriette’s future will be.

And

this makes Henri and Henriette finding one another for the briefest of moments

so important and so romantic and so tragic.

Normally I am not a huge fan of tragic romances – I prefer my romances

to end happily, thank you very much – but Henri and Henriette were too soulful,

too perfect for me to not fall in love with myself. Renoir has this effect on me. He goes to a similar place, although not with

romantic lovers, in The Rules of the Game, by so tragically speaking of unrequited

love and class differences. A Day

in the Country is similar in terms of his ability to uncannily peel

back the outer layers of a story to get at an incredibly sad universal

truth.

In

terms of the filmmaking, although I cannot be certain, the beginning of the

film feels far more finished than the end.

I wouldn’t be surprised if the unfinished portion is the second

half. The opening is full of joy and

happiness and bright sunlight. A nice

moment is when Rodolphe throws open the shutters of a window to see Henriette

playing on the swings. Music erupts from

nowhere, and it’s pure joy – and pure Renoir.

The finale, full of wistful regrets and what might have been, feels far

too hasty and slapped together, and here is where it’s clear the film is

unfinished. However, this fact doesn’t

keep the story from being any less powerful.

I

like romantic movies, but my taste in them is a little different from

most. To me, A Day in the Country hits

an almost perfect note of brief joy and lifelong sadness. I admit right now, I find it utterly romantic. Oh, Henri and Henriette, why couldn’t Renoir

have found a way to give you a proper length film? I so badly want to see more of them, more of

their day together, or more of their brief reunion. But I can’t.

I only have this, and it’s not even available on DVD. Something’s better than nothing, I

suppose. I’ll choose Renoir’s take on

romance any day.

|

| The second meeting. |

Arbitrary

Rating: 9/10. High? Yes.

But that is how strongly I fell for Renoir’s story of Henri and

Henriette. It’s a fragment of a tale,

but when it’s got the goods, it works for me.