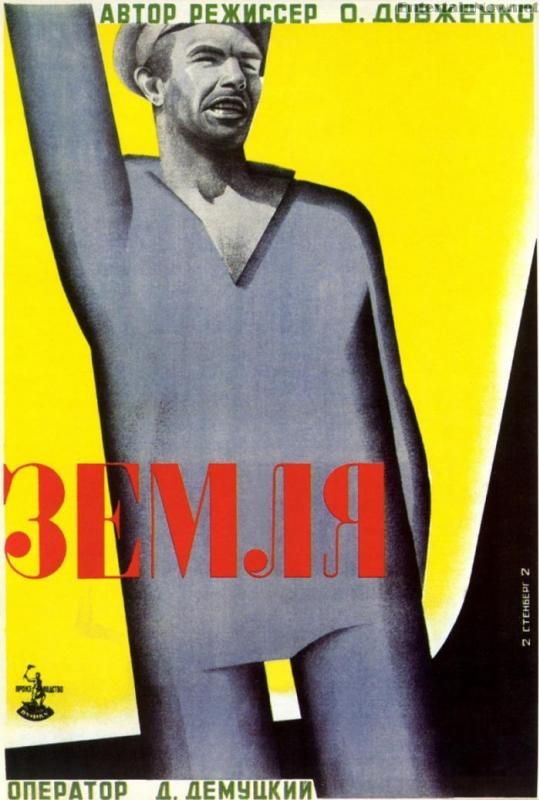

Earth

(Zemlya)

1930

Director: Aleksandr Dovzhenko

Starring: Nature and a tractor and

Ukrainian farmers, in that order.

I

don’t know. I just don’t know about this

movie. It’s… I don’t know. According to 1001 Movies, this is

Dovzhenko’s “ode” (their word, not mine) to the beginning of collectivization

in Russia. Sure it is, that’s totally

the message I got from this one, whatever you say.

So

this is what I could make of the plot: a small village of Ukrainian farmers

celebrates life and death and tractors.

People die, babies eat watermelons, the rich farmers battle it out with

the poor farmers, and tractors.

Something about a son dying, which is different from the old guy dying

at the beginning of the film, and there naturally is a scene where the men are

rallied into a political frenzy. And

then tractors. And awesome Russian

beards. And apples. Because, y’know, they’re apples.

My

favorite parts of this movie were, in no particular order:

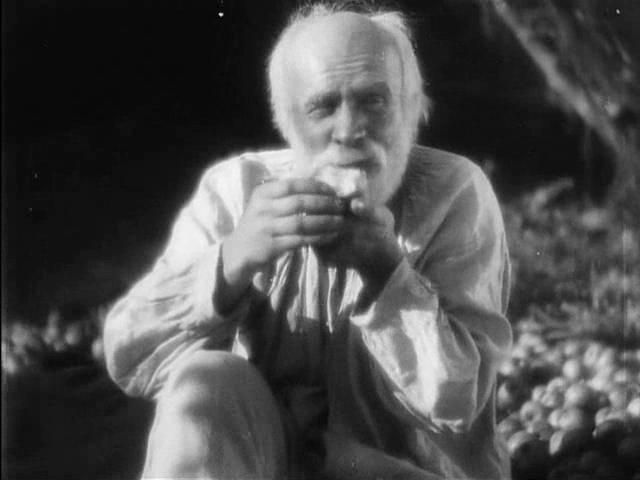

- How Simon, apparently on his deathbed, sits up with zero effort, demands something to eat, has an apple, then says “Well goodbye, I’m dyin’.” And then lays down and dies. That was awesome.

- How a man is argued to about politics for five minutes, but we have no intertitles about what the political guys are saying. They just yell and yell and yell and he listens. Then they leave, and he says, with intertitles, “Well I’ll be a sonuvabitch, them fellows are real class!” I bet they were, after yelling at you for five minutes straight.

- Simon’s epitaph. Right after Simon dies, the only thing anyone says about him is “He liked pears.” That’s a good epitaph. I want my epitaph to be “She liked pears.”

- The utterly ridiculous “bumpkin-izing” of the English translation of the intertitles. I watched this off of Netflix streaming, and Kino popped up at the beginning of the film, so I imagine this is the Kino edition. That being said, great effort was made to turn the Russian intertitles into country rube speech. “Let ‘er fly,” “There ain’t no god,” “You dyin’ Simon?” “Where ye be down there?” Nothing like silly intertitles to make you laugh.

- The apology that came at the beginning of the film. Before the movie even started, I had to sit through several minutes of an onscreen essay explaining why this was an “important film.” Here’s a hint: this does not bode well for me if the distributors of the film feel the need to justify the film’s place in history. The film should speak for itself. If I want to research the history and politics that surround this film, which I usually will to some extent, then I will do so on my own. The essay felt like a thinly veiled apology for the silliness of the movie, a weak attempt at justification.

- How the filmmaker actually got a horse to nod his head in agreement with the farmers. That’s doesn’t feel like Mr. Ed at all, oh no, and it certainly helps make the movie more serious.

- The tractor is the real star of the film. People talk about it with the same verve and excitement as the Wonderful Wizard of Oz. So when the tractor goes kaput on the way to the village, the men naturally piss on it to make it go. And then it does. That was awesome.

- The five-minute long walk this guy takes down a dirt road and then he randomly breaks out in a dance. And then he gets shot or something. The best part was I wasn’t able to tell which character he was for his long, slow, and ridiculously drawn out nighttime stroll. You want me to feel sympathy for this, Dovzhenko? Then you need to do a much better job making it clear exactly who it is walking down the road.

- The never-ending funeral dirge. That was fun. Because I need to see every step of a five-mile-long march played out in real time. That makes for good cinema, oh most definitely.

|

| I like apples. |

The

theme of life and death and nature is clearly Dovzhenko’s main point, pouring

on a little bit of politics as well.

When Simon dies at the beginning, he is (rather inexplicably) surrounded

by piles of apples, and we keep on cutting to blowing fields of wheat. Dovzhenko is definitely making the point that

death is simply a part of nature. We get

similar cuts to nature throughout the film, always reminding us that we’re part

of the great Circle of Life.

The

politicking, though, is a bit odd, especially as everyone in the film are

farmers. There are good farmers and bad

farmers, and little reason given for their differences. I will give the film the benefit of the doubt

and lay it on my ignorance. I am willing

to bet that if I was watching this movie as a member of 1930s Russia, I would

have a much better idea what was going on with the politics of the time. All I get from this go around, however, is

that the rich farmers are evil bastards because they’re evil. And that’s about it.

The

sequence where wheat is harvested was actually the most exciting part of the

film, and where Dovzhenko managed to make a pretty darn good montage. Helped along (greatly) by a frenetic

soundtrack, we follow along from the beloved tractor pulling up the wheat to it

being carted off to a factory and eventually turned into loaves of bread. It wasn’t a story, per se, but it was a neat

little bit to the film. And god help me,

it honestly was more exciting than anything else in the movie. Isn’t that a little sad.

|

| Yay wheat! |

Quite

frankly, if I’m going to submit myself to a Russian propaganda film, I’d pick

something else entirely. I’d want

Eisenstein. At least Eisenstein has the

ability to conjure up some propaganda-fueled anger. This film is curiously emotion-free. It’s just trees and fields and villagers

running and tractors. And because it’s

emotion-free, holy crap but it feels long, which is a very bad sign because

it’s not long, not at all.

Should

you watch it? Sure, if you like

tractors. Or wheat. If not, though, take a pass.

Arbitrary

Rating: 3/10.