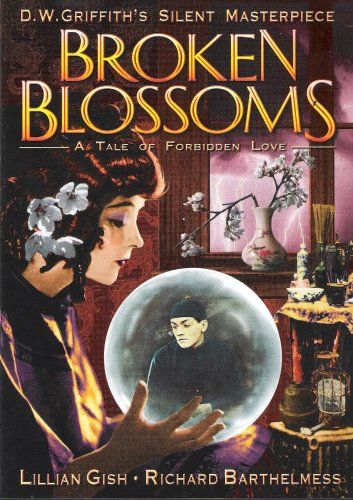

Broken

Blossoms

1919

Director: D.W. Griffith

Starring: Lillian Gish, Richard

Barthelmess

Silent

films are curious. They are so far

removed from the cinema we know today that it can be difficult acclimating to

their distinctly separate style. There

are certainly exceptions to this rule; great films are great films regardless,

but only a handful of the silents I’ve seen have managed to break through their

constrictions of time and place and really, truly impress me. Films like Keaton’s comedies, City

Lights, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, or The Unknown are examples

of this. Unfortunately, Broken

Blossoms does NOT fall into that category, feeling instead like a film

ridiculous in how utterly out of date it is.

Cheng

Huan (Barthelmess) starts off in China as a well-intentioned missionary who

means to go to London to spread the word of the peace of Buddha. Once there, however, he becomes addicted to

opium and winds up tending a grubby little shop in the Limehouse district. Lucy (Gish) is a waif who shuffles to and fro

in between beatings by her cruel boxer of a father. Cheng falls in love with Lucy from afar, and

one night, when Lucy is left on the streets, he takes her in, feeds her, and

nurses her back to health in the most chaste way possible. Of course everyone will pay for this act of

kindness.

Let’s

deal with the obvious first, shall we? This

being 1919, Hollywood (and America) wasn’t nearly as progressive as it is today

(and frankly, I’m not so sure it’s terribly progressive today). We have, in Broken Blossoms, a

thoroughly American actor playing a Chinese character, complete with squinty

eyes and everything. Oddly enough, this

doesn’t completely bother me. I know

it’s repugnant by today’s standards, but is it fair to hold Broken

Blossoms up to today’s standards?

I tend to be pretty tolerant to issues like this in very old films, and

when you look at the characterization of Cheng Huan in Broken Blossoms rather

than simply the outward caricature, he actually becomes the kindest character

in the film. I don’t like watching

Barthelmess play an Asian any more than the next blogger, but I have to hand it

to Griffith for making the Chinese character the closest thing the film has to

a hero, and this in the middle of a phase in American culture called “Yellow

Peril” where the fear of Chinese immigrants was reaching a peak. It’s an odd feeling, really; I very much wish

that white actors weren’t playing people of color in Broken Blossoms, but at

the same time, I respect the presentation of Cheng Huan in a positive light and

understand that the film is ultimately a product of its time.

No,

far more than the whitewashing in Broken Blossoms, the thing that

turns me off about the film is the unrepentant Melodrama with a capital

“M.” Melodrama, as a genre, has never

sat well with me. Even as a young teen

Siobhan, I cringed when having to read books in school like Sister Carrie

or any of the “young adult” fiction foisted upon me. When I was in middle school, I remember being

agog at all my classmates who insisted on writing the most utterly ridiculous

short stories and poems about drugs, abuse, suicide and the like, none of which

were realistic, and all of which ended badly.

Consequently, I dislike films where I have to watch things go badly in

the most predictable way possible and with as little nuance as can be

managed. And Broken Blossoms is

definitely that film. Lucy’s father is

evil for no other point than to be evil and brutish because the plot demands

it. Oh, okay, sure, I don’t need any

kind of believability there, go right ahead.

Gish’s Lucy is so tortured in her childhood that she cannot physically

smile and must actually use her fingers to curve her mouth upwards. To pull out a phrase from my youth, gag me

with a spoon. This style of filmmaking,

so popular in the early days and certainly around albeit a bit evolved today,

does less than nothing for me. I really

dislike melodrama. So Broken

Blossoms never stood much of a chance.

A

few comments on Lillian Gish in this film.

In general, I am a fan of La Gish; it’s difficult not to be, considering

she’s one of the pioneers of cinema. I’m

not sure how much I like this particular performance, however. For one thing, there is the age of her

Lucy. In 1919, Ms. Gish would have been

26 or 27 years old. I cannot for the

life of me figure out how old the character of Lucy is supposed to be. In some scenes, it appears as if she’s meant

to be late teens; in others, more like 13 or 14. For her part, Gish plays Lucy on the immature

and infantile side, having her entranced with a simple doll and completely

unaware of the feeling of love directed at her from Cheng Huan. Frankly, skewing Lucy so young, even if it’s

only emotionally that young, makes things a bit… squicky. It’s a bit worrisome already that I’m trying

to overlook historical whitewashing, but now I have to watch an older man fall

in love with a woman who has the mental capacity of a 12 year old girl. This does not for fun times make.

But

there is one scene in particular where Gish shines, and that is the scene where

she has locked herself in a closet to escape the temper of her father, who has

just discovered that she had been inside Cheng Huan’s shop. Here is where we really see Ms. Gish’s acting

prowess, as she convincingly gives us a performance of a frightened and

cornered animal incapable of seeing a way out.

The naked fear on her face is staggering, and she is sole reason why I

found this scene the most emotionally affecting of the entire film. Her face, her body language, everything is

committed to the feeling of true dread.

I

suppose I need films like Broken Blossoms every now and then

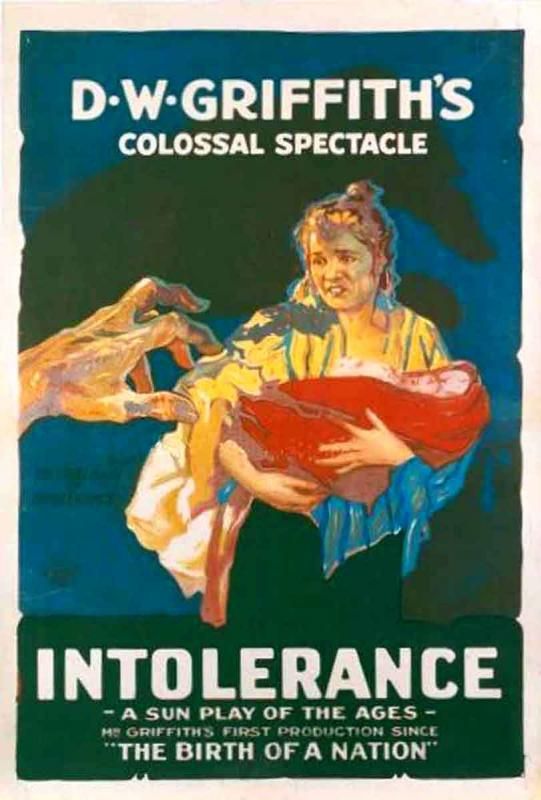

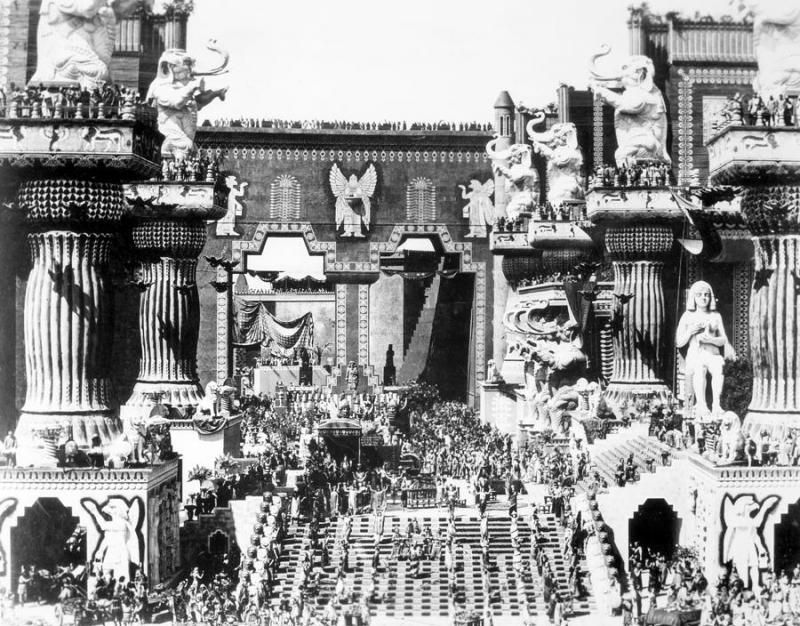

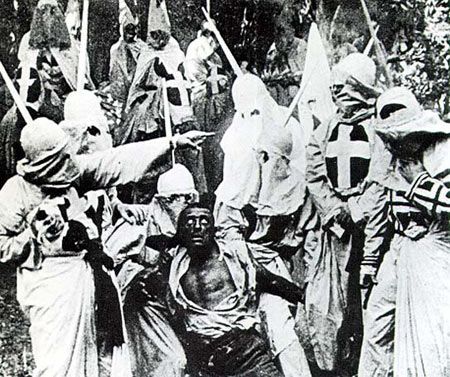

to remind me just how amazing other silent films are by comparison. It’s not nearly as preachy as Intolerance

or as hateful as The Birth of a Nation, but I’m still not a fan. Melodrama’s not for me, thanks.

Arbitrary

Rating: 5/10