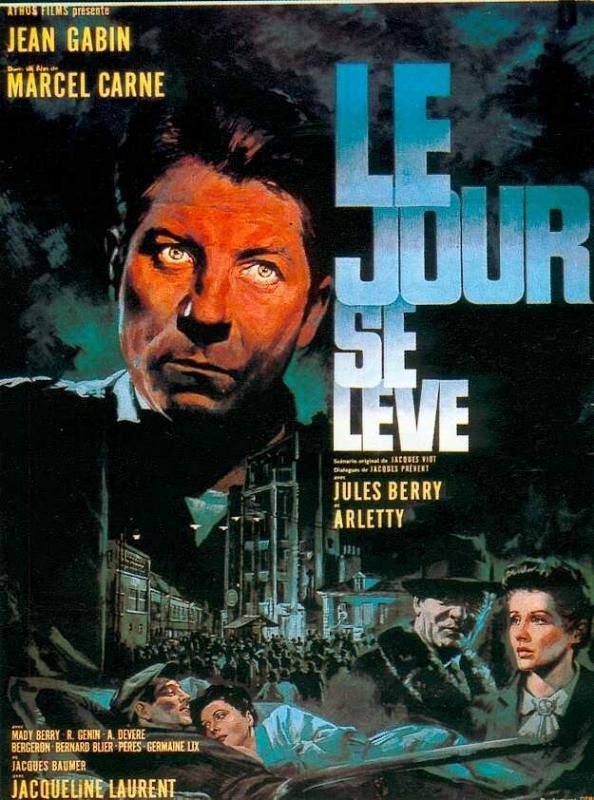

Le

Jour se Lève (Daybreak)

1939

Director: Marcel Carné

Starring: Jean “Studmuffin” Gabin,

Jacqueline Laurent, Arletty, Jules Berry

Film

noir, as a genre, is most definitely considered an American creation. French film critics of the 1950s and 1960s

noticed that certain American films from the forties and fifties had developed

a distinct tone, look, and shared thematic elements, and they coined the phrase

“film noir” to describe it. In spite of

the French name, though, they were talking about American films, and most will

agree that film noir really started in the early forties. But I really start to question all of that –

that noir is an American cinematic invention, that it started in the early

1940s – when I watch Le Jour se Lève. I suppose it doesn’t fall as neat and tidily

into the film noir category as other classic noirs, but it’s so damn

close. It must have been influential in

helping develop the genre.

The

film opens as François (Gabin) shoots a man (Berry) in his apartment building,

then barricades himself in his room, refusing to open up to the police. He flashes back to how he wound up in such a

situation, starting with meeting pretty Françoise (Laurent), with whom he fell

deeply in love. But Françoise is not as

innocent as she looks, and soon we learn of her history with Monsieur Valentin,

a dog trainer, circus performer, general con man, and, coincidentally, the man

that François shoots. In between spats

of jealousy over Françoise and the lies that Valentin feeds him, François also

meets Clara (Arletty), Valentin’s assistant, who knows all Valentin’s tricks

and isn’t nearly the picture of innocence that Françoise is. His life with these two very different women

who share him and the dastardly Valentin in common flashes before him and leads

him up to the night of the shooting.

Although

Le

Jour se Lève is definitely dark, even nihilistic, Carné is smart and

doesn’t take us there right away. He

lets the doom and gloom build slowly, and when we see François’ first

flashback, he’s positively beaming with happiness. To me, this is where the film hooks me. I buy François and Françoise so implicitly as

a couple, and I so adore their early scene of pretend homemaking together, that

I become emotionally invested in both their fates. This scene is so important in the film as it

points out with humor but also pathos just how desperately François longs for

normality in his life. Growing up an

orphan, he feels a connection to Françoise because she was also raised in an

orphanage. As the two of them potter

around her landlord’s house at night while the landlord is out, they play act a

fantasy where it is THEIR house, THEIR ironing, THEIR children who left the toys

out. This dream of mundane domesticity

is everything to François, and he speaks sincerely of marriage and a future

with Françoise, and I’m just putty in his hands. I’m all in.

I want everything for François. I

have bought into the central relationship and the central character of the

film, and everything that happens afterward will be that much sadder because of

it.

|

| Um, yes please. |

Clara

and Françoise are an interesting pair of women to involve François with, as

they are so much opposites. At first

glance, Françoise is the girl you take home to your parents, all innocence and

sweetness and light, and Clara is the girl you ring up for a booty call because

you know she’ll oblige. What I like

about Le Jour se Lève is how it subverts these expectations. Françoise is not nearly as innocent as she

looks (a revelation that eats away at François as he contemplates the fact that

his darling Françoise is still in love with her shady ex), and Clara has hidden

emotional depth. Every time François

thinks he has everything sorted out, every time he thinks he has a handle on

one or perhaps both of these women, something new comes to light and once again

he realizes he is wrong. I like these

women. They are more than caricatures. As the film hurtles towards its gloomy

finale, these two opposites are even revealed to have so much more in common

than we ever could have thought. Rather

than resigning them to broad strokes, they have depth.

|

| You have no idea how much I want to be Arletty in this scene. |

Shall

I go on my typical “Jean Gabin = sex god” rant?

Sure, why not, it’s my review.

Jesus Christ, but Gabin is MY KIND OF MOVIE STAR. The male actors I find most attractive

definitely share certain traits, and Gabin has them in spades. First of all, he can act. If an actor is ridiculously awful, no amount

of good looks will sway a damn thing for me.

He’s excellent in Le Jour se Lève at detailing

François’ increasing desperation as he falls deeper in love yet is stymied too

many times by Valentin and his awful hold over Françoise and Clara. Gabin has to take François from very cheery

guy to someone who, whether he meant to or not, shot a man at point blank

range, and he has the range to do it.

Not only is he good at showing François’ emotional journey, but he also

has the task of bringing François through the standoff with the cops, a

harrowing process indeed. When you add

on to all of this the sort of rugged, everyman quality I *really* like in an

actor, I’m hooked. I don’t like my

Hollywood hunks to be prettier than me.

I like some rugged, dirty sex appeal, something less dressed up and more

organic. Let’s put it this way – Marlon

Brando in A Streetcar Named Desire makes my ovaries explode, while

Orlando Bloom does absolutely nothing for me.

Gabin has that same sort of Brando-esque appeal. I can’t help it – I’m crushing on him

hardcore. He acts, he broods, he swoons,

he goes crazy, and (shoutout to Movie Guy Steve) his hair is fantastic. And yes, I'm using this review to shamelessly post sexy pictures of him.

|

| Jesus effing Christ, slice me off a piece of that. |

When

you take all these elements and add on the noir-in-training of the film, how

could this not be a hit with me? It

really shouldn’t be a secret that this film ends badly; when it opens with

François shooting someone, you can just sense it’s all going to cascade

downhill at some point. I love the

plodding of the soundtrack, moving, unrelentingly, toward the film’s conclusion. There are drumbeats, like a funeral dirge, punctuating

the soundtrack frequently, as François knows only too well what waits for

him. Carné’s photography transitions

from brighter lights in the first half of the film to the significant darkness

of the second half as the desperation ratchets up to the brink of no return.

I

wonder, a bit, at this film being made in France in 1939 with WWII breaking out

in Europe. The sense of fatalism, of

moving toward a foregone conclusion, of being unable or unwilling to fight any

longer, is this what some people in France felt? It must have colored the filmmaking; how

could it not? I believe wholeheartedly

that those American filmmakers who would go on to create the iconic noir of the

next decade must have taken a heavy cue from Le Jour se Lève.

Arbitrary

Rating: 9/10. And one additional note:

when I first started watching films from 1001 Movies, this one was

unavailable anywhere. I am very pleased

to see that in the years since, it has been given the Criterion treatment

(“Essential Art House”) as it deserves to be preserved and seen. Also, I smell a Jean Gabin movie marathon in

my future.