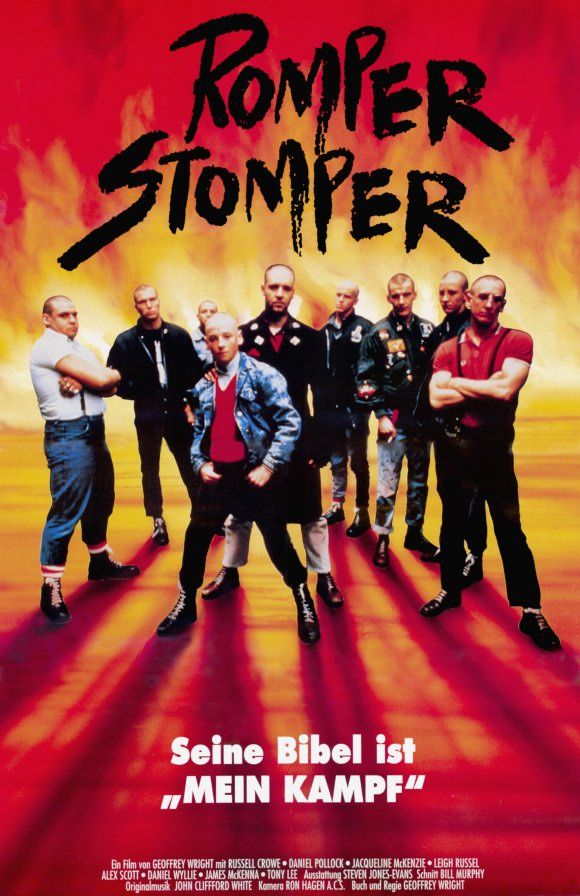

Romper

Stomper

1992

Director: Geoffrey Wright

Starring: Russell Crowe, Daniel

Pollock, Jacqueline McKenzie

Romper

Stomper is

many things, but one thing it is not is apologetic. “Unflinching.” “Gritty”

“Intense.” Yes, yes, and

yes. It’s also rather unpleasant. That’s not a bad thing per se, but the scant

90 minutes that you spend with this movie will not be the happiest of your

life. It’s perhaps most famous as the

film that put Russell Crowe on the map, and although I’m not the biggest

Russell Crowe fan in the world, it’s easy to see why he became a star after his

turn here. What I ultimately take from Romper

Stomper, though, is a bromance flick found in a rather unexpected

place.

Hando

(Crowe) is the de facto leader of a group of neo-Nazi skinheads living in

Melbourne. Davey (Pollock) is his best

mate and right hand man. Enraged at what

they perceive to be an encroaching Vietnamese population, the gang enacts

brutal retribution on local Asian innocents.

Epileptic and drug-addicted waif Gabe (McKenzie) catches Hando’s eye,

and she begins accompanying the gang on their beatings. One day, the Asians start to fight back

against the gang in a brutally lethal manner, and this triggers the slow

disintegration of the group that plays out for the rest of the film. Eventually, we are left only with Hando,

Davey, and Gabe, and the inevitable violent love triangle.

|

| Hando's insane. Seriously. Insane. |

There

is a lot of hate in this movie. Hi, it’s

about neo-Nazis. You can’t expect

heaping loads of tolerance and love.

Even knowing this in advance, it’s still very hard for me to stomach

this type of cruel bigotry. Hando’s gang

is as brutal as a bunch of thugs can get without guns. Watching them beat the crap out of random

people for no sane reason at all is a challenge. But much in the same way that A

Clockwork Orange starts with several ruthlessly cold fights then shifts

its focus, Romper Stomper does as well.

(In fact, there are many parallels between these two films.) After a long and chaotic fight where the

Asian community fights back and fights back hard, the skinheads are no longer

all-powerful. They are beaten, bloody,

and they have been forced into a humiliating retreat. For me, it helped me to watch the rest of the

film knowing that this group was not invincible. Knowing that such hateful speech and cruel,

unnecessary actions would ultimately have to be paid for made the bitter pill a

little easier to swallow. There is still

controversy to this day as to whether this film glorified the skinheads or was

a testimonial against them. I see

nothing about any kind of glory in this movie; it is particularly

unglamorous.

After

the turning point fight, the movie changes its momentum. The gang is on the run and they are breaking

down. The story shifts from being about

skinheads to being about Hando, Davey, and Gabe. This is a much more typical and common movie

story – two guys and one girl – but I was intrigued and invested in it. What really helps to set apart this

particular love triangle, because criminy we’ve seen a billion love triangles

before, is that it plays up all three angles of the triangle instead of just

two. This is not merely a story about

Gabe and Hando versus Gabe and Davey.

Hando and Davey’s relationship is just as important, if not more so,

than either of their interactions with Gabe.

Skinheads are hardly gentle people, but watching Hando put a makeshift

pillow under Davey’s head when Davey is passed out drunk is surprising in its

kindness. Hando kisses Davey several times,

and Davey seems to be the only one in the group who can exert any sort of

control over Hando. Hando may be having

sex with Gabe, but he loves Davey. Even

Gabe herself notes to Davey, “Hando doesn’t act like he likes me. He likes you, though, doesn’t he.” Indeed, when I first smelled the triangle in

the air of the film, I wasn’t entirely certain if it was because Davey wanted

Gabe for himself, or whether Davey wanted Hando for himself.

How

strongly is the male love angle played up in Romper Stomper? Well, I’ll put it this way. In an extended home invasion sequence

(another massively huge tip of the hat to A Clockwork Orange there), the piece

of classical music heard in the background is Bizet’s “Au fond du temple saint”

from the opera The Pearl Fishers. “Au fond du temple saint” is one of the more

famous pieces from all of opera. It’s a

duet between a tenor and a baritone, and in it, the two men sing about how they

both fell in love with the same priestess, but that they decided to give up their

love of her because of their friendship with one another. This song was not chosen randomly. Any piece of classical music may have

sufficed, but no, Wright picks one that specifically mirrors the plight of

Hando, Davey, and Gabe. This is total

and full-on bromance, albeit of the psychotic variety.

Additionally,

the performances of all three players in the triangle are very strong. Russell Crowe as Hando embraces his inner

psychotic, playing him with a frighteningly quiet power. The characters I fear the most are those who

do not shout and make lots of unnecessary noise, and this is Hando. Crowe is great in Hando’s physicality. Again, it’s easy to see why this movie was

the first step in propelling him to stardom.

As for Davey, Pollock is all shyness and unassuming gentle nature. He’s even likeable! Well, as much as a skinhead could be. Pollock manages to play the harder role of the

quiet sidekick who secretly, and maybe even unknowingly, wields power over the

leader. As the girl who comes between

them, McKenzie is the Australian drug-addled gang version of a manic pixie

dream girl. I like that McKenzie gives

Gabe her own strength, making her no one’s victim and not in need of any man to

take care of her. I like the touch of

Gabe’s wardrobe changing as she became more entrenched in Hando’s gang; she

goes from girlie frocks to a military style sweater and boots, but then back to

her original frock when she strikes out again on her own.

Perhaps

the reason this triangle works so well on screen is because, unnerving as it

may sound, there were apparently real life parallels. While filming, McKenzie and Pollock were

romantically involved. For his part,

Crowe had made a film prior to this with Pollock (Proof) so the two had

clearly worked together before and formed a bond. Sadly – very sadly – Pollock, himself a heroin

addict, committed suicide weeks after Romper Stomper wrapped filming by

throwing himself under a train. Russell

Crowe’s band wrote a song about it, called “The Night That Davey Hit the

Train.” This kind of awful true story

gives the tale that’s played out in Romper Stomper an extra dose of

tragic pathos.

The

sound choices are very good. The score

is full of very hollow effects, lots of echoes, and a great deal of sounds that

remind me of metal on metal. It gives

the film a vicious, biting feeling, but also one that underlines the emotional

emptiness of the skinhead lifestyle. The

only thing most of the gang members feel is blind hate. What sort of existence is that, to be

compelled by such an empty feeling?

It

took two days and two viewings of Romper Stomper for me to finally

decide where I stand on it. Watching the

first half is difficult, because that is when the neo-Nazi skinhead mentality

is presented most fully, and neo-Nazi skinhead philosophy is not pleasant. However, I think the triangle of Hando,

Davey, and Gabe that takes center stage in the second half is one of the most

intriguing, intense, and oddly enough, emotionally compelling relationships

I’ve seen in some time. The final beach

scene is one that sticks to my ribs, infects my brain, and refuses to let me

forget it.

Hando

and Davey: psychotic skinhead bromance, for real, yo. Hando + Davey 4-eva.

Arbitrary

Rating: 8/10. As distasteful as it first

seemed to me, I really like this one.

It’s not pleasant, oh no, but it’s intense and compelling.