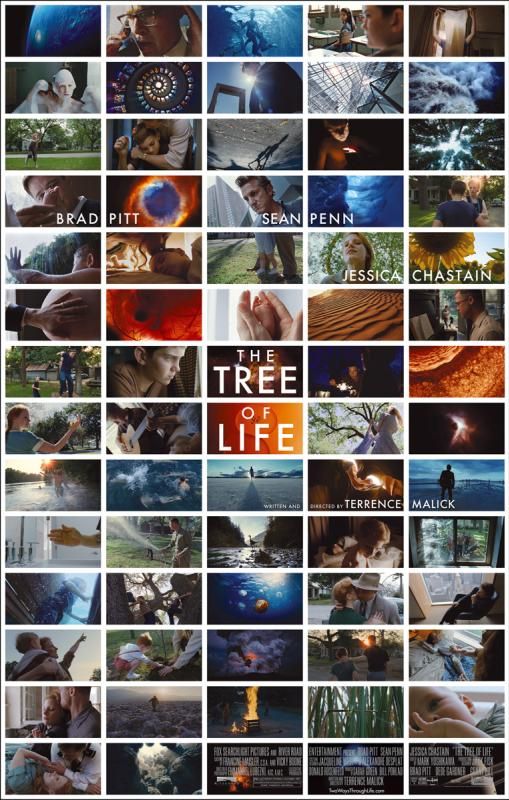

The Tree

of Life

2011

Director: Terrence Malick

Starring: Brad Pitt, Jessica Chastain,

Sean Penn, Hunter McCracken

Oh,

Terrence Malick. Malick, Malick,

Malick. With The Tree of Life, you finally

said “FUCK YOU” to the concept of “narrative” that had been plaguing you most

of your career and just did whatever the hell you wanted, didn’t you. No more mucking around with pesky plot when

all you really want to do is shoot pretty pictures.

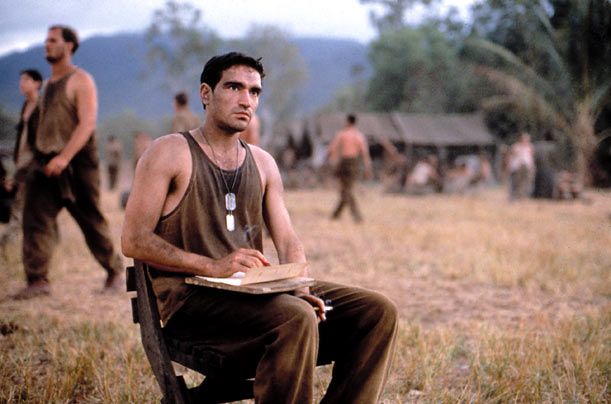

Tree

of Life is

“about” (yes, the quotation marks are warranted) a boy named Jack (Penn as

grown man in modern times, McCracken as an adolescent in the 1960s) who has a

difficult relationship with his strict father (Pitt). His mother (Chastain), on the other hand, is

all softness and tenderness. Through

this loose set up, we examine the concept of tension throughout all time, the

birth of the universe, the concept of how to live life, and questions of

faith. That is, I think that’s what’s

supposed to be going on.

I

will say this flat out from the start: there is good stuff here in Tree

of Life. There were parts of it

that I found pretty damn awesome. In

fact, for the first half of the two hour plus run time, I was on board with

this movie, prepared to write it a glowing review. But then… then Malick lost me, and he never

really got me back on board.

So. Let’s take these two halves of the film

separately, shall we?

The

first half starts with some non-linear flashbacks of our main character Jack

remembering some stories of his parents, of the death of his brother, and we

meet him as the man he is today. The

only way I can describe the opening introduction of these people is dizzyingly

exciting. The camerawork is amazing,

especially in the early Sean Penn modern sequences. It’s all tall, bright lines, gleaming silver,

and vertigo-inducing spins. I don’t mean

that as a knock; on the contrary, I was enthralled. Sure, there’s little (re: nothing) in the way

of traditional story here, but I actually didn’t care. I’ll repeat that: this section was so

imaginative, I didn’t care I wasn’t being told a regular story. I felt, rather than followed. This was about emotion, not plot, and I was

connecting with the emotion. Sure, I

didn’t know the particulars of Penn’s apparent existential angst, but Malick

was more than able to convince me of it nonetheless with absolutely amazing

photography.

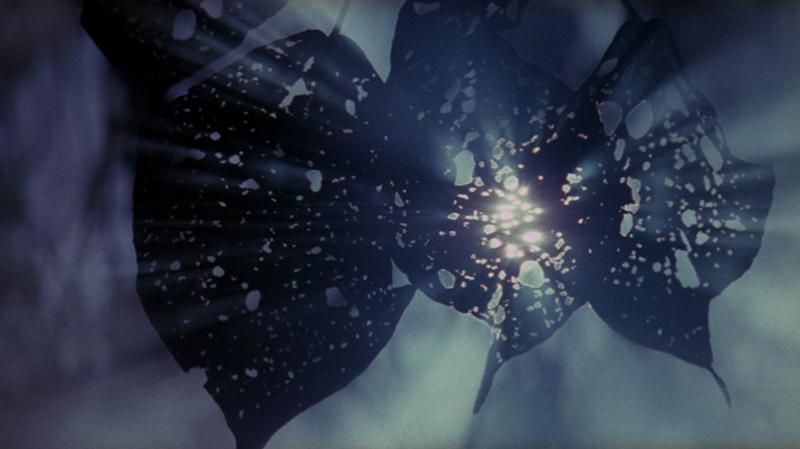

And

then we move into what Chip from Tips From Chip calls “The 50 minute long music

video,” a not unfitting description.

After this initial establishment of the fundamentals (angst-ridden grown

son with father issues, brother who died while young, Jessica Chastain is a

soulful mother, Brad Pitt is a strict father), we go into Malick’s treatise on

the concept of tension throughout the ages, going back to the very origins of

the universe. The film I have heard most

frequently referenced when discussing this section of the film is Kubrick’s 2001:

A Space Odyssey. There are

certainly parallels here, especially when considering the similarities in space

shots (one at the end is basically Malick re-enacting Kubrick) and a focus on

aggression, but that was not the movie I thought of. Instead, I read this segment of the movie as

Malick’s version of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring segment from Fantasia. In both of these, we move from the formation of

the universe to the formation of the planets to the appearance of the oceans

and single celled organisms, even dinosaur sequences and the destruction of the

dinosaurs. While the Fantasia

segment is easily more brash and audacious while Malick’s version is more soft

and contemplative, they share a great deal in common. After this pretty darn fantastic series of

scenes, Malick then does a fast-forward to the mother and father of the opening

as we watch them establish their family.

This is still in what I call “the first half” of the film, and it is

absolutely full of joy. We get snapshots

of Jack’s early life as a baby and a toddler, scenes of his life with his

mother, of playing with blocks and no small amount of billowing window curtains

(I think Malick must have wet dreams about billowing window curtains, he loves

them so much in his films). Just like

the opening, this is not really about characters or stories but about emotions,

the love and openness of family and childhood.

And although the jump from the destruction of the dinosaurs to Jack’s

early childhood is certainly a pretty big leap, chronologically speaking, I

accepted it. The film was still working

for me.

Until

we get to what looks like thirteen year old Jack.

And

then we move into the second half.

How

long does Malick need to convince me that Jack hates his dad? Because holy fuck on a stick, I GET IT. JACK HATES HIS DAD. You don’t need over an hour of tiresome,

repetitive, and not at all magical or glorious segments to make me understand

this. The second half of the film loses

nearly everything that made the first half special and interesting. I do think, as I said before, that this is a

film more about certain emotions than a definitive story, which is why,

perhaps, the portion of the film that is most clearly story-driven worked so

incredibly little for me. I actually

wish that Malick had cut off the film after the first half, making instead an

odd little movie that’s just over an hour long that has modern building shots,

sixties-era neighborhood shots, and dinosaurs.

Because that would have been way better.

The

second half drags on interminably. The

message that Malick is trying to say is that Brad Pitt is kind of a shitty dad

despite the fact that he thinks he’s being a good dad. Over and over again. Beating you over the head. I just… OMG MALICK I GET IT. I FUCKING GET IT. And it’s not nearly as profound as you think

it is. Boy hates dad. Dad is mean to family due to a variety of

reasons.

Who

the hell cares.

Not

me.

See,

I’m not even capable of intelligently tearing down this second half of the

movie because it pissed me off so much.

And

then there’s the ending of the film. The

whole “Bad Dad” story wraps up, and I thought to myself, “hey this feels like

the end of the movie, this would make a nice end.” But then it wasn’t. There was more. And I thought again, “hey, THIS feels like a

good end of the movie.” But then it

wasn’t. There was still more. And now I was thinking, “OK, this feels

weird, but I guess it COULD BE the end of the movie.”

And

then it wasn’t.

By

the time Malick actually got around to REALLY finishing the film, I was foaming

at the mouth. END THIS GODDMAN THING

ALREADY. The second half of the movie

was so stale that Malick’s attempt to recapture the magic of the imagery of the

first half fell completely flat. It felt

pretentious and self-indulgent and utterly stupid. Which is interesting, because I suppose it

wasn’t nearly so different from the stuff at the opening of the film, yet I was

much more accepting of Malick’s “high art” style at the beginning of the movie

than I was at the end. He had overdrawn

his account, and I was no longer tolerant.

I saw this at the Dryden, so I was in a movie theater, and I was so

fucking ready to leave, I couldn’t wait for the final fade-to-black. I practically ran out of the theater to my

car. And that’s not good.

There

were, however, two aspects of the film that were superb from start to

finish. The cinematography throughout is

just stunning. Frankly, I’ve come to

expect that of Malick, so it wasn’t really a surprise, more a

confirmation. Malick makes damn pretty

movies, and Tree of Life is no exception.

He can make anything look good, be it volcano sequences, CGI dinos, DDT

smoke, or the twilight hours of neighborhood playing. The other aspect of the film that was

excellent was the soundtrack. I honestly

cannot think of a better classical music soundtrack than that which he uses in Tree

of Life. Every piece feels perfect,

absolutely perfect. Every piece smartly

underscores a very particular emotion, and as this is a film about emotion, not

plot, that’s necessary. I LOVED the

soundtrack. I honestly can’t remember

the last time I was so impressed with a classical music soundtrack. I want to own it, and I rarely want to

purchase a film’s soundtrack. It was

perfect. It was sublime. It was heavenly. Malick furthers his comparison with 2001

in this respect; Kubrick was Da Bomb in terms of being able to uncannily pick the

perfect piece to accompany his films, and Malick, with Tree of Life, is the only

other director I’ve seen who comes close to Kubrick’s skill in this

respect. Given the little Kubrick

fangirl that I am, that is high praise.

It’s

hard for me to decide where to come down on The Tree of Life, really

hard. The first half is very good. Not for everyone, not at all, but it worked

for me. The second half was tedious and,

by the end, infuriating. Where do I

land, then, on a movie that I myself am so split on? Right in the middle, I guess.

Arbitrary

Rating: 6/10. OK, it’s not right in the

middle – the strong first half, soundtrack, and cinematography bolster up the

utterly inane second half to a passing score.

Recommended only for the self-avowed cinephile, and even then, with some

reservations.