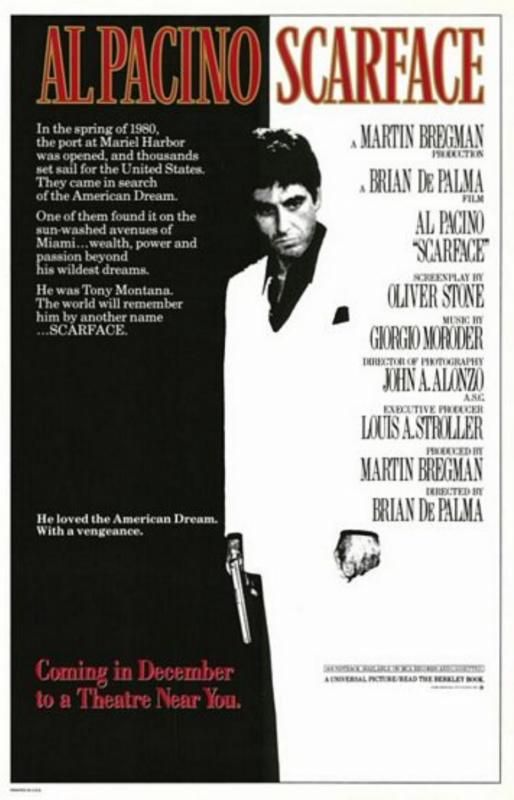

Scarface

1983

Director: Brian De Palma

Starring: Al Pacino, Steven Bauer,

Michelle Pfeiffer, Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio, Robert Loggia

Scarface is one of the more notable

titles on my “List of Shame.” It’s

achieved a definite presence in pop culture that persists to this day, finding

new fans amongst the young all the time.

I ask my students questions about their likes throughout the year (“Favorite

comedy,” “Favorite dessert,” “Favorite author”) and nearly every year, Scarface

will get a few mentions in various categories.

While it feels good to be able to check this film off, I’ll say right

here, right now, it was a film that was precisely what I thought it would be,

and I didn’t think it would be for me.

Tony

Montana (Pacino) arrives in Miami from Cuba in the late seventies after

essentially being told to leave his homeland by Castro, who purged his land of

political dissidents and a fair share of criminals. Montana falls in the latter category. He and his friend Manny (Bauer) work their

way into Miami’s drug syndicate by catching the attention of boss Frank Lopez

(Loggia). Montana, for his part, pays

attention to Frank’s girl, Elvira (Pfeiffer), a woman who doesn’t exactly

follow the rule of “Don’t get high on your own stash.” Tony is cruel, hard, and ruthlessly

ambitious, so it is inevitable that his climb to the top of the drug power ring

comes at a cost. When his beloved sister

Gina (Mastrantonio) becomes drawn into this world, however, Tony’s problems

push him over the edge.

While

not the start of Pacino’s acting career, I will make the case that Scarface

was the start of Pacino’s overacting career.

Pacino’s work in the seventies was phenomenal. I think of The Godfather and its

first sequel, Serpico, and Dog Day Afternoon, and Pacino

delivers intense yet fairly subdued performances that rise when they need to,

but also fall when they need to. But in

Scarface, we have the start of the Pacino that has now become a caricature, a

performance that is nothing but highs and yelling and shouting and

craziness. To be fair, from what I’ve

seen of his filmography, this was the first time he turned in a character whose

volume is set at eleven throughout the entire performance, and people were

obviously impressed. If I hadn’t known

Pacino for such a type of character, I’d have been far more impressed with his

turn as Tony Montana. But the problem

with seeing iconic films after you’ve already seen a metric ton of other films,

though, is that you lack this historical perspective. To me, this is just another example of Pacino

being over the top, crazy Pacino. It

felt like a Pacino caricature. It felt

like I had seen it all before during skits on Saturday Night Live. And

personally, I’d rather have the seventies Pacino.

Scarface is so eighties, it hurts. It physically hurts me. Which, of course, is fitting, because Scarface

is all about excesses, and so were the eighties. As this film came out early on in the

eighties, it is also easy for me to see how Scarface’s success could have

shaped and defined this sort of celebration of immoderation throughout the rest

of the decade. The sets are utterly ridiculous,

reeking of gilded age glitz and spending money like it’s going out of

fashion. Tony’s estate in the second

half is painfully eighties. Then there’s

the montage sequence halfway through that separates Tony’s rise from his

fall. Shown with the requisite synthesizer

music in the background, it was so stereotypically eighties, it actually made

me laugh. I threw my hands up in the air

and bent over, I was laughing so hard. I

suppose there’s little else for me to do than embrace all the ridiculous

eighties trademarks in Scarface, though.

I

was irrationally bothered by the – hm, do I actually call it racist? Yes, I’ll call it racist – racist casting in Scarface. Almost the entire cast of characters, with

only a few exceptions (the most notable being the fact that Manny, a

significant character, is actually played by a Cuban), are meant to be Hispanic

– Cuban, Colombian, Bolivian – but only the minor characters and extras were

actually played by Hispanic actors. What

was most galling was the decision that Italians = Cubans. Pacino, Loggia, Mastrantonio. This really, REALLY bothered me, and although

this sounds odd, I’m not entirely sure why.

It’s certainly nothing new in film; look at the movies from the twenties,

thirties, forties, etc, and just how much blatant racism they contain. White actors playing black characters, white

actors playing Hispanics, white actors playing Asians. I tend to forgive this when I come across it

as a “sign of the times.” Unfortunate

and ugly, yes, most definitely, but, well, it was how Hollywood used to

operate. I find myself willing to

overlook it. Why, then, am I so bothered

by the exact same idea in Scarface? The only possible answer I can come up with

is that I had hoped that by 1983, we would have known better. By 1983, I think I was hoping I wouldn’t have

to sit through the painful experience of watching Robert Loggia, an actor who

celebrates his Italian roots, ridiculously try to pull off a Cuban accent. I didn’t buy it, not for one damn second. I didn’t buy Mastrantonio, I didn’t buy the

actor who played Sosa. I marginally

bought into Pacino as Tony, but that was the only one. Am I being irrational here? I might be, and I completely own up to

that, and on reflection, I don't expect ALL of the actors to be of Cuban descent. And yet, there's something that gets under my skin about seeing actors who are not only not Cuban, but AGGRESSIVELY Italian (for the most part) playing Cubans. It reeks of blackface to me. As I said, I know that I am

willing to forgive similar faults in older movies. Why can’t I forgive it here? I'm not entirely sure, but it was a major block to my involvement in the

film.

|

| She's all, "Bitch please, you ain't even CLOSE to Cuban." |

One

thing I will definitely say Scarface got right is knowing

precisely how to pull off a remake. As

readers of this blog undoubtedly know, this Scarface is a remake of Scarface,

sometimes subtitled “The Shame of the Nation,” from 1932 starring Paul

Muni. Both films follow the same general

plot structure – aspiring mobster rises then falls from power – but feel worlds

apart. And that right there is precisely

what a smart remake ought to be. Scarface,

the remake, doesn’t try to pull off a thirties gangster picture, but instead

introduces the drug syndicate angle, something that would have resonated far

more with modern audiences. It feels

current and slick and stylish, and not at all like it’s trying to simply copy a

film that came before. What’s more,

there are several reverent touches in Scarface, the remake, alluding to

the original, to show that De Palma and producers really do respect their

predecessor. The message “The World Is

Yours” is significant in both films, and De Palma actually dedicates his Scarface

to the writer and director of the original Scarface.

Scarface is a fairly straightforward

story of someone’s rise and fall from grace.

Nearly every plot device it employs was telegraphed to me miles in

advance, so absolutely nothing came as a surprise. Then again, I am most definitely not the

film’s intended audience. Ultimately,

though, it is nice to have seen this film, even if I have zero compunction to

see it again; it is a film that survives, it is still seen and loved and quoted

by today’s youth, and if nothing else, I can now laugh at Kendra’s obsession

with it when I guiltily watch reruns of Girls

Next Door.

Arbitrary

Rating: 5/10.