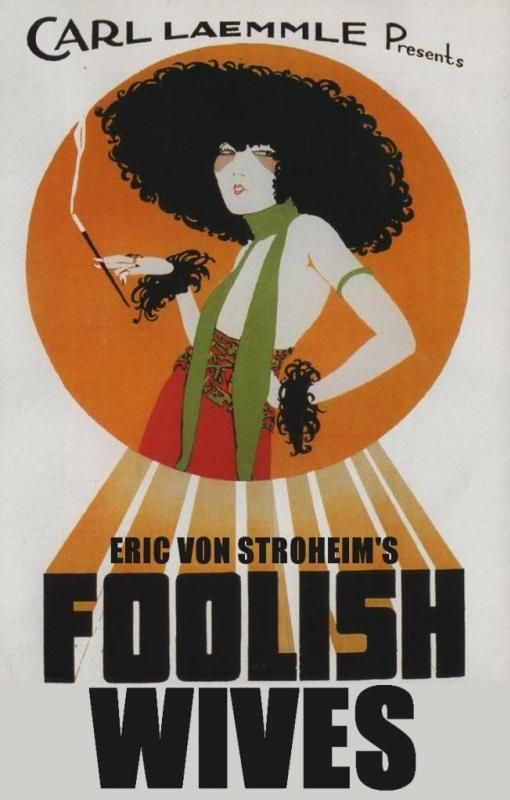

Foolish

Wives

1922

Director: Erich von Stroheim

Starring: Erich von Stroheim, Miss

Dupont, Maude George, Rudolph Christians

Erich

von Stroheim has done it again! Jump

with joy for the anticipation of an overlong, completely over the top morality

play! Oh thank goodness, because there

really isn’t enough of that in my life at the moment.

“Count”

Sergius Karamzin (von Stroheim) is a con artist masquerading as an aristocrat,

preying off of the gullible upper class in Monte Carlo with the aid of his

“cousin,” Princess Olga Petchnikoff (George).

When an American dignitary (Christians) and his much younger wife Helen

(Dupont) arrive, the tricksters immediately set their sights on fleecing the

couple for everything they have. Sergius

sets to work charming Helen, slowly, of course, and trying to keep the husband

relatively unaware. Ultimately, however,

Sergius’ womanizing ways catch up with him.

As

I watched Foolish Wives for a second time, I kept on trying to put my

finger on what the story reminded me of.

Was it soap opera? No, soap opera

moves slower than this. Was it crappy

romance novels? No, crappy romance

novels have a hero, and Foolish Wives has no hero, just

ridiculous naïve characters and Evil Villains of Evil. And then it finally hit me. I thought to myself, “Sergius is Don

Juan.” Which then made me think Don Giovanni, (in particular, Mariusz

Kwiecien in Don Giovanni… mmm,

Mariusz Kwiecien…) Mozart’s operatic reimagining of Don Juan. And that’s precisely what Foolish

Wives is: it’s an opera plot without the actual, y’know, opera.

Now,

I am a definite fan of opera. Like,

pretty darn big time. All my students

know it. All my friends know it. Opera rocks, man. I will preach this from the highest hilltop.

But

Foolish

Wives does NOT rock, despite this association I made. Why?

The last thing I’m looking for from my opera is plot, and that’s ALL

that Foolish

Wives has going for it.

The

plots of operas are not the point of the opera itself. If you wanted interesting story development,

no one in their right mind would think, “I know! Let’s all hit up Il Barbiere di Siviglia tonight!

That’s got one crackerjack plot!”

The operatic plots are mere scaffolds on which fantastic music is

hung. What’s more, they are usually

simple to their core. Any opera I’m

familiar with can be summed up in two sentences, three at the most. If it’s a comedy, it’s “mistaken identities

prevent the hero and heroine from proclaiming their love for one another while

a baritone gets in the way.” If it’s a

tragedy, “everyone makes bad decisions then dies.” Yes, I’m oversimplifying, but not by

much. And opera plots are notoriously

slow to progress. Because the plots are

so simple, there isn’t a tremendous amount of plot progression, and the story

can move rather slowly. The arias are

rarely about plot progression in an opera, instead being about the fabulous

music. Even my mother, whose only

experience with opera is when I’ve tied her down and shoved some Juan Diego

Florez in her eyeballs, noticed that “everyone tends to repeat themselves in

the songs, just singing the same thing over and over.” Yes, exactly.

And what they’re repeating is usually something straightforward, like “I

love her.” Or “I hate him.” Or “Wow, I’m

so happy.”

To

bring this back to Foolish Wives, imagine now that simplistic plot that operas

have, where everyone says the same thing over and over again, where the plot is

ridiculously slow to progress, and then remove the awesome music from it, and

you have this movie. A plot so utterly

simple – con man corrupts gullible wife – and a story that moves so damn slowly

– I don’t understand why this has to be two and a half hours – that is

absolutely full of the characters doing or saying the same thing over and over

again – how many scenes do we need of Sergius being a smarmy bastard to

Helen? Add them all together, and you

get Foolish

Wives, the non-opera opera story.

I don’t watch opera for plot, I watch it for tremendous singing and

amazing music, both of which Foolish Wives lacks, making the whole

movie rather dull.

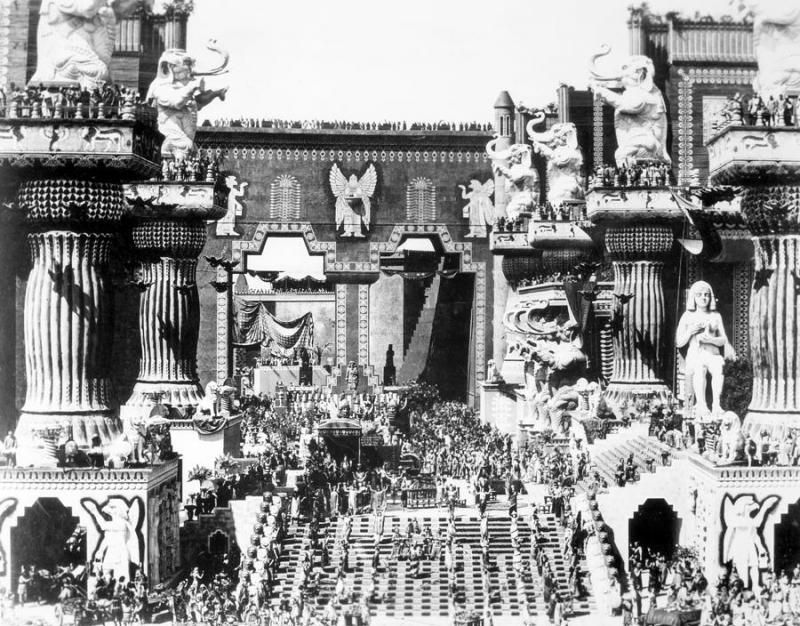

What

is impressive about Foolish Wives are the sets.

Watching this through, I assumed it was partially shot on location

somewhere; if not Monte Carlo itself, then a spot that looks like Monte

Carlo. But no, it wasn’t. Nope, von Stroheim being the egotistical

bastard he was, he built Monte Carlo, complete with a fake lake, in studio

backlots. Alright, von Stroheim, I’ll

give you your due, that’s rather amazing.

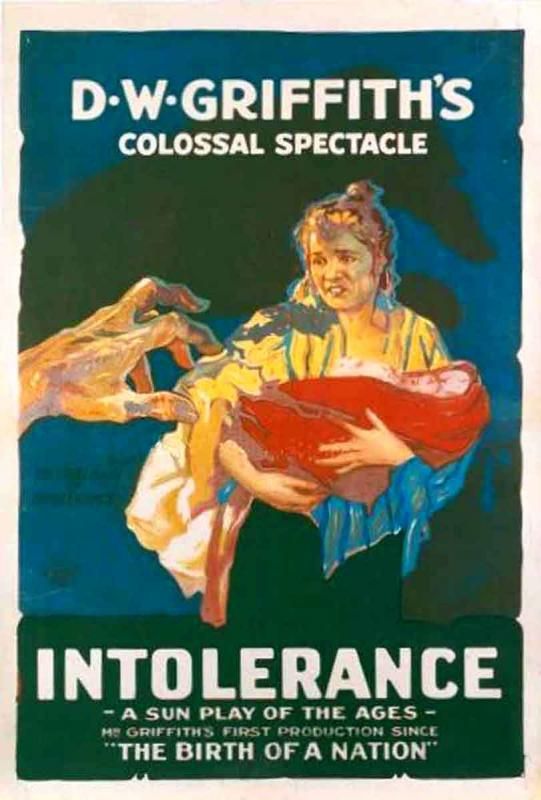

Although not perhaps as grand as some of the set work in Intolerance,

it’s pretty close.

Many

silent films do not translate well with modern audiences. There are some that do, and some that are

still spectacular today, but most feel dated in many ways. Time has not been kind to Foolish

Wives. The story is one that modern

audiences would barely register an interest in, and when you throw on von

Stroheim’s ego in insisting this be an “epic” in terms of length, what results

is a product few would find compelling.

Arbitrary

Rating: 4/10