Taste of Cherry

1997

Director: Abbas Kiarostami

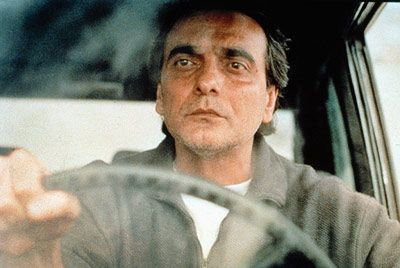

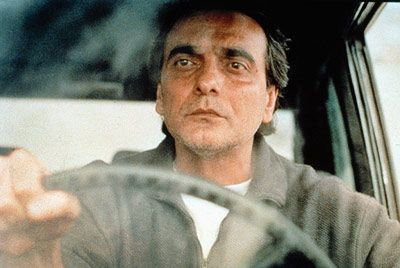

Starring: Homayoun Ershadi

Loud, raucous, and ebullient are NOT words to describe

Taste of Cherry. Philosophical, allegorical, and pondering are FAR better descriptors, as well as it being quietly critical of government and religious institutions. Impressive, especially considering this is an Iranian film.

Mr. Badii (Ershadi) is driving around in his car. He keeps looking at people on the side of the street. Some of them, he appears interested in; others, not so much. Eventually, he takes three strangers, one at a time, for a drive through the rolling dusty hills at the outskirts of Tehran, and offers each of them the same job: to bury him after he commits suicide, or save him if the attempt doesn’t work.

I adore ambiguity in film. I love it when a filmmaker trusts his or her audience well enough to allow them to make up their own mind, to allow them to draw their own conclusions about a film, rather than having to explicitly explain every tiny little thing. And wow, but is this film ambiguous on so many levels. Which, therefore, makes it awesome for me, but which, I will concede, make it incredibly frustrating for others.

No reason is ever given for Mr. Badii’s suicide ideation. I love that. It makes the film less about Mr. Badii’s individual story, and much more about mankind in general. Here is a man who is apparently healthy and wealthy and wants to kill himself. The film is definitely not so concerned with the why, but much more with the implication of the actual act. How the three strangers react to the idea is telling. The soldier, the theology student, and the nature lover – each displays markedly different responses to Badii’s proposition, and these reactions are, to me, more telling than any possible reason for Badii’s suicide in the first place. The government, the church, and nature: how is suicide viewed by these various institutions?

Ershadi’s performance as Mr. Badii is one of the finest restrained performances I have ever seen. He has a Herculean task as an actor: portray a suicidal man to an audience who is never given a reason for it. At the beginning of the film, before we know what this mysterious job entails, he can’t be too desperate in his actions, otherwise he would scare off prospective grave diggers. He seems like an ordinary middle-aged man who, for some reason, keeps inviting strangers to have a ride with him. When the truth comes out, Ershadi gradually makes Mr. Badii more and more desperate, but not in a gratuitous way. He paces, he rubs his hand together, he looks around nervously. We – actually, I’ll rephrase that, because so much of this film is in how you personally read it – I can see him starting to worry about getting someone to take care of him in his final hours, but also start to rethink the whole thing. In his final of the three conversations, with a Turkish taxidermist, Mr. Badii, who has, to this point in the film, dominated the conversations, is significantly suddenly silent. This is the man who has finally agreed to bury him. Why has he stopped talking? Instead, the taxidermist takes control of the situation as Badii silently sits and drives. Through his silence, Ershadi portrays so much emotion. In one of the final scenes of the film, we see Mr. Badii only through his curtained apartment window; even from a distance, Ershadi had me on the edge of my seat. I was drawn in. I was entranced. I really cannot say enough about this performance. It does everything it needs to without ever, EVER being over the top.

I find it incredibly telling about Kiarostami’s philosophy that he has a main character who wants to kill himself, but in order to kill himself, he must make connections with other people. For whatever reason, Mr. Badii wants to die, but he also cannot die without reaching out to the human race first. I interpret this as a profoundly humanist viewpoint from Kiarostami. Badii does not close himself off, but rather opens himself up to others, even in his darkest hours. Is this Kiarostami sharing a story of his past with us? I believe so.

Before writing about a film, I like to research it a bit in various places. To my shock, Roger Ebert gave this film one star when it came out. His critique? Boring. Really, Roger? That’s it? The film was boring? I argue vehemently against this. Although it’s not fast-paced, the film managed to build tension quite effectively through Ershadi’s carefully evolving performance, and at the end, I was on the edge of my seat with concern for Mr. Badii, wondering if he would actually go through with it or not. And a tremendous amount of what a viewer gets from this film is based on how much the viewer puts in; how I read the three passengers might be wholly different from how others read them, and Kiarostami leaves the door open for multiple interpretations. I really wonder if Roger Ebert should watch this film a second time; after all the health issues he’s had in the past ten years, I wonder if he wouldn’t read Badii’s journey a little differently now.

Ultimately, I am cautious about who I recommend this film to. It’s not a typical story, not told in any sort of typical manner, and it’s far more ambiguously allegorical than any standard Hollywood fare. If metaphysical discussions and minimalist cinema are your bag, then I cannot recommend

Taste of Cherry enough. If you think

Inception was a little slow-paced, then dear god, steer clear.

Arbitrary Rating: 9/10

I wrote this review about a month ago. I have since seen a second film of Kiarostami's, and I am even more fascinated by

Taste of Cherry than I was at first.

Taste of Cherry had real staying power with me. It's one of those movies that just wouldn't leave my brain. Made me like it even more. Dare I say that I'm becoming a Kiarostami fan girl? Perhaps!