Monday, November 5, 2012

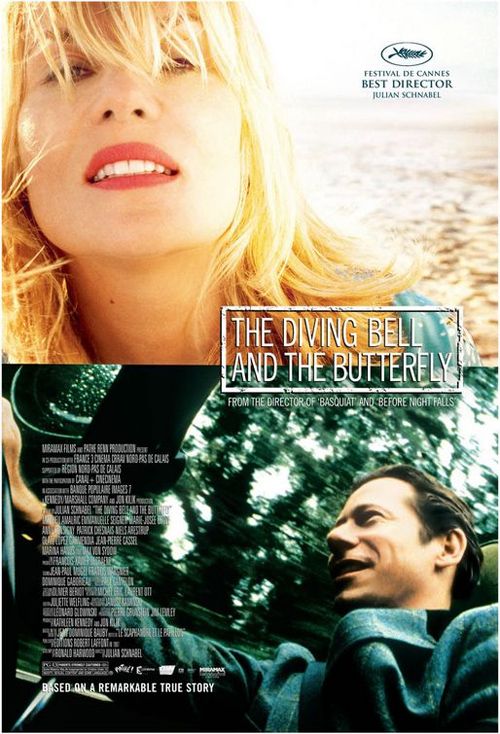

The Diving Bell and the Butterfly

The Diving Bell and the Butterfly

2007

Director: Julian Schnabel

Starring: Mathieu Amalric, Emmanuelle Seigner, Marie-Josée Croze

Jean-Dominique Bauby (Amalric), or Jean-Do to his friends, is a highly successful editor at French Elle. The film opens when he wakes up from a stroke, completely paralyzed from head to toe, save for his left eye. Jean-Do, after running the gamut of emotions about how completely his life has changed, starts working with a therapist (Croze) to learn to communicate again. She reads him the letters of the alphabet and he blinks when she gets to the one he wants to use. He decides to dictate a book using this method about his experience as a man trapped in his own body.

The first half hour of the film is entirely from the point of view of Jean-Do. As the film opens, we see a hazy, foggy, slanted view of a hospital room. The camera goes in and out of focus repeatedly. We are seeing through Jean-Do’s functioning eye, and it is tired. We are disoriented and confused because he is disoriented and confused. We continue to experience exactly what he does as a string of doctors and specialists come in to see him. The camera continues to be blurry and at odd angles. The first time we actually see Jean-Do in his stricken state is as he sees himself in a reflection along a shiny wall. He shudders at his reflection, and frankly, I did too. When a friend visits him and puts a fuzzy hat on his head, part of the camera shot is blocked by the hat because part of his vision was blocked by the hat. Both Schnabel and Janusz Kaminski, the cinematographer, did an amazing job in creating the first-person camerawork. I’ve never really seen anything else like it.

Just as I was starting to feel that the blurry, jittery first-person camerawork, as great as it is at helping me understand as much as possible what Jean-Do is going through, was getting tiresome, the camera starts to pull back. We start seeing wider shots, and seeing Jean-Do from a distance. The reason for this change appeared to be increasing acceptance by Jean-Do of his condition. As soon as he stops pitying himself, the camera widens. Schnabel is making the point that his very limited world became much larger as soon as he started to make some sort of peace with new body.

All of the characters in the film are blessedly real. Jean-Do, as the protagonist, is not a hero or a saint, simply a real man who is trying to come to terms with the blow that life has dealt him. We gradually learn of his life prior to his stroke, and while he isn’t evil, he is clearly egotistical, arrogant, and a womanizer. But he also loves his children, loves his father, and, after his stroke, greatly appreciates those around him. He is human, plain and simple. It was refreshing, quite frankly, to see a flawed human being in a human tragedy. Nor does Jean-Do’s stroke suddenly turn him into an angel. He still expresses that he wants to see his girlfriend, despite the fact that his ex-wife (Seigner) has visited him frequently but his girlfriend has never come to the hospital. The stroke does, however, give him a determination and a clearer outlook on life. A very well developed main character.

The way Schnabel weaves Jean-Do’s memories, fantasies, and dreams into the film is gorgeous. Just as if Jean-Do suddenly nodded off in the middle of a visit, we might be thrown into a recollection of his out of the blue. Both the fantasies and the memories are awash in color and grandeur, beautifully presented. What’s more, I greatly appreciated that the memories we saw were not just “the lead-up to the stroke.” Some memories were significant, and some were not. Many were out of order with one another. But isn’t that how we ourselves go through our memories? When I’m thinking back on my life, I don’t go through it chronologically. I pick one day or event and think about that. Then I think about something completely different. Schnabel’s direction is truly a tour de force.

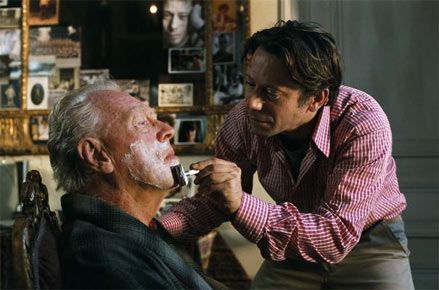

The two most touching scenes in the film to me were the two that involved Jean-Do’s relationship with his father, portrayed by Max von Sydow (seriously, that dude’s in everything). In the first, a memory, Jean-Do visits his elderly father, who is stuck in his apartment because he cannot climb stairs anymore, and shaves him. It’s a great example of a minor event from one’s life that had wound up having tremendous meaning. As the father and son talk to one another, it becomes clear that there is great love between the two. Although neither expresses it in an overt way, the feelings are there. I found out from the special features that in that scene, Mathieu Amalric asked the propmen to use a real razor, so yes, he is actually shaving Max von Sydow.

The second scene between Jean-Do and his father is after his stroke. His father calls the hospital and speaks to Jean-Do over the speaker phone. Not gonna lie, as soon as Jean-Do heard his father’s voice and his left eye went into convulsions, I started bawling like a little baby. I really resent overt melodramatic sentimentalism in film, but this scene is the complete antithesis of that. It has a ton of heart without beating you over the head with the tragedy of the situation. It’s a perfect little film moment. Jean-Do’s father is beside himself, clearly frustrated that he cannot visit his son, nor can he hear his son’s voice answer his questions. Sydow had me in absolute tears, and Amalric’s clear emotional reaction despite Jean-Do’s paralysis is heartbreaking. And, to be honest, it was such an affecting scene that remembering it while writing this last paragraph had me in tears again.

The story of The Diving Bell and the Butterfly is true; Jean-Do was a real person who really did blink out his memoirs using only his left eye. My favorite thing about this movie, though, is how it completely bucks the typical presentation of a biographical inspirational movie. It is thoughtful, elliptical, and beautiful. There is a distinct poignancy throughout the film, and yet it never got bogged down in mires of depression. This is probably due to Jean-Do’s optimism. Both a sad movie and a feel-good movie, it’s also very unique in its photography. Easy to understand why Schnabel was nominated for Best Director.

Arbitrary Rating: 8.5/10

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Very good review. I liked this movie, but I didn't love it. The scene where he shaves his father was a highlight for me. Believe it or not, another is seeing Marie-Josee Croze recite the alphabet.

ReplyDeleteIf you'd told me I could remain engaged for something like that I would have laughed, but she's so damn gorgeous that I was willing to watch her face when all she was doing was forming letters.

I agree that I didn't wholly love it... somehow, I was taken to the edge but not pushed over it.

DeleteLike you, I was never disengaged from the recitation of the alphabet - which is unexpected! Croze was fantastic. Pretty much everyone in the film was fantastic.