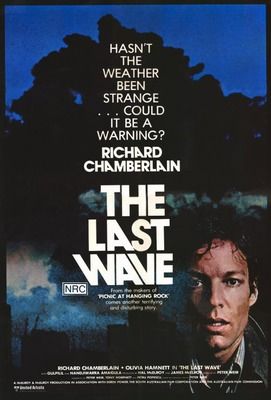

The Last Wave

1977

Director: Peter Weir

I am a ginormous fan of Peter Weir’s early Australian films before he went all Hollywood, before he became predictable. I don’t know how he managed to do it, but he has the dubious honor of being the ONLY director I can think of who made a film that cracks my all-time top ten list (Picnic at Hanging Rock) AND made one of my most hated films of all time (Dead Poets Society, a movie that pushes all the wrong buttons). Luckily, The Last Wave is far closer to the former than the latter, as it is definitely one of his early films. It is a film that has to be Australian, a director exploring his country and its conflicts in one of the only ways he knows how: through mystical film.

David Burton (Chamberlain) is a tax lawyer who gets inexplicably brought on to help defend a case of five Aboriginal men accused of killing another Aboriginal in modern day Sydney. One of the five men, Chris (Gulpilil), is the only one who will talk to David, but he won’t talk about the night of the killing. The more David gets involved with Chris and Chris’ old friend Charlie (Amagula), the deeper he seems to sink into a mystery. Unexplained weather and strange dreams; are these frightening portents of things to come?

For me, this film is all about mood; a fantastic, spiritual, uncertain, threatening mood. What Weir does so well is to create this mood, then let it wane, then bring it back, then ratchet it up. The ever so slight slow motion shot, thrown in when you’re not expecting it, or the ceaseless ping heard on the soundtrack when you expect it to be quiet, or a casual shot of something we've seen before, making it completely unclear as to what we are being shown is fact or fiction. As one of the seminal directors of the Australian New Wave movement of the 1970s, Weir’s most significant contemporary (in my opinion) was Nicolas Roeg. I mention this because I swear, the two of them must have had conversations about this concept of elliptical storytelling and slightly sinister mysticism.

In fact, I find the mood of this film so compelling, I would even say that this film is far more about images and tone than about dialogue. When The Last Wave gets to the point where it is necessary to have characters speak in expository fashion, it is the weakest. Gulpilil is a very fine actor, but his best scenes in this movie are ones of very quiet power and charisma; when he is forced to “explain” what is happening, it drags the movie down. Ditto for Chamberlain; ditto for everyone else. In some scenes, Weir makes it clear that the dialogue is completely irrelevant. The banal conversation at a barbecue or dinner party is hushed and muted, as if Weir is telling us it’s okay not to pay attention to these words. In other scenes, expository scenes, the dialogue tries to explain what is happening, and it all feels so weak. There is so much power in the mysticism and imagery of the film that trying to use mere words to explain it cheapens the experience. I like this movie best in the dream-like sequences, or when the characters speak in terms of symbolic poetry; there, the film is so beautiful and enchanting and thrilling and fascinating. I like it least when the characters feel the need to explain everything.

“What are dreams?” David asks Chris in a dinner conversation (and my favorite scene of the film). Chris ultimately responds that dreams are “a shadow of something real.” So much of the movie is about this concept of dreams and their meaning, and it’s one that is not often committed to film; at least, not quite like this. This is what I like about this movie. Much like dreams, the meanings of many things in this film are left unexplained. There is ambiguity in what is going on. Do you believe that David is actually having dreams that tell the future? The movie makes very little attempt to answer that question, and god bless it for that. I love it when directors have faith in their audience; faith that they are intelligent enough to interpret the film their own way, intelligent enough to extrapolate what they see into a meaning all their own. I don’t like to have every last thing spelled out, least of which in a movie where explanations are cheap. Therefore, for me, this becomes a very personal film. I know how I interpret the movie; I completely buy in to the magic it hints at. Which surprises me, actually, because I am a student of science, a skeptic, and not at all a spiritual person in my real life. I would much more expect to take a hard line on all the funny hand-waving, but Weir’s world is so entrancing, I fall under its spell. He has me; he caught me in his web, and I will buy in to anything he presents me. The dream sequences and their obscure meanings are utterly fascinating.

Apart from the idea of dream states and their meaning, man’s relationship with nature is explored as well. Throughout the whole movie, very strange weather phenomena keep occurring. We open with a small school in remote Australian countryside that gets pummeled with a bizarre thunderstorm; bizarre because there are no clouds or dark skies. The rain seems to come from nowhere. Hail follows, breaking the windows of the school. From this point forward, water is in nearly every scene in the film, making you think about what the title The Last Wave really means. A policeman idly fingers a dripping faucet; a rainstorm follows David home from work; the wall outside the courtroom has a small trickle running down it. It is as if nature is constantly trying to find its way into this nice little civilization we’ve built for ourselves. Our rules and buildings and finery are all very well and good, but nature is so much more powerful, and can – and will – break down the flimsy barriers we have erected against her. David seems to sense this; as the film goes on, he breaks more and more from the societal rules thrust upon him, and seems to become more involved with the odd natural world around him.

I love ambiguous filmmaking. I love filmmaking that poses questions it will not answer; or, at the very least, not answer completely. The Last Wave has moments of terrific beauty and awe and gauzy mysticism. It also has moments that don’t work as well, that feel clunky and unnecessarily expository. I completely admit that; this is not a perfect film. It’s not my favorite film by Weir, nor my favorite Australian New Wave film. For me, though, the good outweighs the bad, and the tone and images and dreamlike world that Weir manages to create here, so much like that he created in Picnic at Hanging Rock, place this film solidly in the top of his filmography for me.

Arbitrary Rating: 8.5/10. Achieves moments of greatness, but is a little unsteady.

Believe it or not, I've actually found a place where we might disagree on something. I like Weir's work a lot more than you (although I agree on the overwrought Dead Poet's Society). I like many of his more recent films.

ReplyDeleteThe connection to Picnic at Hanging Rock is a good one. This film expresses the same sort of inexpressible quality for me. There is something here beyond words, something that is true only in depth of feeling but that cannot be spoken.

Good catch on the sound. I thought it was just me, but I think you're right about it.

I'm bringing this up here because you mentioned it here, but the quote in your review for this film about how Peter Weir has abandoned this moody mystical spirituality in his later films is *really* what I meant about his work. His later work is fine. It's not bad (except Dead Poets Society, a film I hate with the burning of a thousand flames), but it's not... this. So many people make solid compelling dramas. So FEW people dare to make movies like THIS, that dare to delve, without any winking or pandering, into this realm of spirituality. I lament that Weir moved on.

DeleteMe trying to write this review was basically just me flailing wildly about "HOW AWESOME IS THE MOOD OF THIS FILM!!!!" The heart of this film is VERY much beyond words.