The

Thin Red Line

1998

Director: Terrence Malick

Starring: Jim Caviezel, Sean Penn, Ben

Chaplin, Nick Nolte

When

watching this film at the Dryden last night, I came to the realization that

despite the fact that I’ve written over 200 reviews for movies from 1001

Movies, I have yet to review a modern war movie. What fits the criteria of “modern war

movie?” Simple: made in the 1970s or

later, after the Hays Code was lifted and films could be a lot more graphic

about everything. And the reason I

haven’t yet reviewed a modern war movie is because they are, quite possibly, my

least favorite genre of films ever, maybe even less liked by me than

experimental films.

In

The

Thin Red Line, Malick follows the men from C Company as they fight the

battle for Guadalcanal in World War II.

We get inner monologues of many of the men, including

hungry-for-a-promotion Tall (Nolte), desperately missing his wife Bell

(Chaplin), and stoic and cynical Welsh (Penn), but we focus mostly on Whit

(Caviezel). Whit is first seen AWOL,

living an idyllic existence with a tribe on an island in the South

Pacific. He sees the beauty in everything,

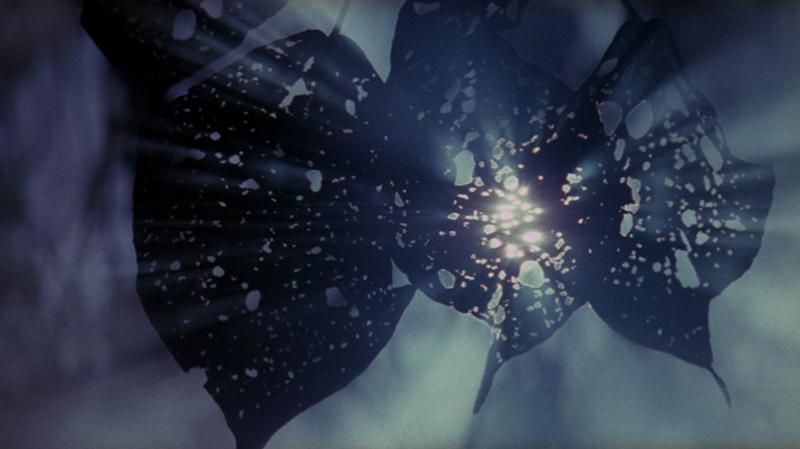

and ruminates on man’s purpose amidst all the chaos of war. There are the requisite battle scenes,

burning scenes, death scenes, fight scenes, bomb scenes, but also Malick’s

characteristic lilting shots of nature.

There isn’t so much a plot as there is an examination of the mentality

of a soldier in war time.

I

think the only fair place for me to start is to explain just why I cannot bear

modern war movies. I can’t take

them. I just can’t. And it all goes back to Saving Private Ryan,

which is a little ironic, considering that was in direct competition with The

Thin Red Line during awards season 1998. Me being a college freshman, who thought I

could handle anything thrown my way, went to go see Ryan in theaters, and I

left the theater traumatized. I don’t

want to go into too much detail (that’ll be for my review of THAT movie), but

suffice it to say there are still scenes from that film that stick in my head

and only come up in nightmares. My

threshold for movie violence, which had gotten higher as I got older, was

utterly crumbled by that film, and I haven’t been able to stomach much violence

ever since.

Which

makes me wonder: what’s the difference between a powerful film and one that

simply hurts the viewer? Because I’ve

seen powerful films that rejoice me, that lead to a grand catharsis and that

ultimately elevate in spite of their crushing power. Those are the powerful films I love. I’ve also seen films like Saving

Private Ryan that beat me over the head and punch me in the stomach for

hours with no intent other than beating me over the head and punching me in the

stomach. Those are the powerful films I

can’t abide. I don’t want to use the

word “hate,” it’s not what I intend, but I cannot stomach them. I cannot deal with them. They hurt me too much without giving me

anything other than pain in return. I

understand that war is hell, I understand the point those directors of modern

war movies are trying to make, but I just can’t take it. Guns terrify me, and war, especially,

terrifies me. Utterly terrifies me. A war movie is like torture for me.

So,

onto The

Thin Red Line in particular, yeah?

Given

everything I said above, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that I rather enjoyed

the first 45 minutes of The Thin Red Line, because it’s the

bit of the film that has the least to do with war. This is where we open with Whit’s new home on

a tropical island, see him swimming with the natives, singing, smiling,

enjoying nature. Even when he has to rejoin

his ship and we start meeting a cast the size of my high school, Malick

maintained the careful rhythm he had established when Whit was on the

island. It was a nice rhythm, a hypnotic

rhythm, and I was fairly well engrossed.

But then, of course, this is a war movie, and when the bombs started

going off, Siobhan’s eyes shut tight, she grit her teeth, she grabbed her arm,

and tried desperately not to give herself new fodder for future

nightmares. There was honestly a full

five minutes where I was resolutely not watching the film. And shots of animals in pain and/or dying

were just as bad – I peaked open my eyes for a second to see a baby bird

flopping around on the ground and then squeezed my eyes shut again in horror,

peaking again to make sure it was over, but it wasn’t. Most of the remainder of the film followed

this path, which is bad for Siobhan. All

the magic of the opening was lost, and although I sensed that Malick *thought*

he reclaimed it, that he *thought* he was once again giving me that lyrical

loveliness of the opening, it never really came back. Now it just felt tedious and pretentious,

quite frankly, as if he was trying too hard.

But then again, maybe his point was you can never go back. Hard to tell with Malick, really.

Of

the myriad of characters in the film, I responded best to Bell and Whit. To be honest, however, one of the reasons I

responded so well to Bell was because I spent the first hour of the film trying

to figure out what I knew Ben Chaplin from, and then, about halfway through the

movie, I remembered – The Truth About Cats and Dogs –

which made the game less fun, having solved the puzzle. Chaplin’s character, Bell, is deeply in love

with his wife (played by Miranda Otto) and thinks of her often. I liked these flashbacks, but Malick,

interestingly enough, begins to question the veracity of these flashbacks. Were these real events, or is Bell simply

dreaming? Has it been so long since he’s

seen his wife that his memory is starting to play tricks on him? I like the suggestion about the fallibility

of memory, especially for a soldier in wartime.

When do memories become dreams, or dreams become memories? It’s an interesting point, and I can see

Malick going to town on this concept.

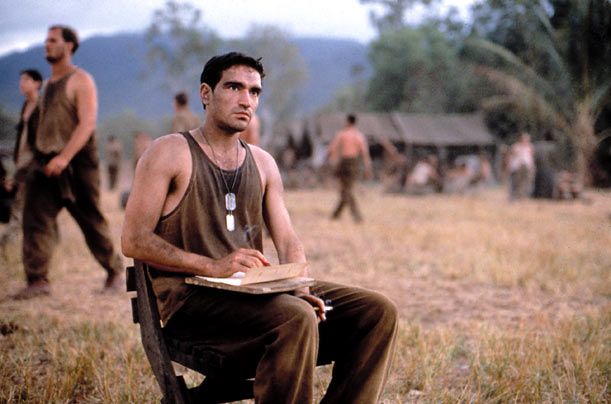

|

| Seriously, once I placed him, all I could think of was Truth About Cats and Dogs. |

Whit,

even amongst a huge cast of mostly anonymous soldiers, is definitely the most

stand-alone character in the film.

There’s a voiceover about three quarters of the way through the film

that talks about the two ways to interpret death, one being either the

inevitability of the event and the sadness, the other being as a means of seeing

a glory, a higher power. Malick is

careful never to reference God specifically, instead implying the sheer power

of Nature on its own, perhaps. Whit, as

a character, is the embodiment of this second philosophy. He insists on being with men when they die in

order to comfort them and pass them on to this higher power. He’s almost Christ-like; actually, perhaps a

bit too Christ-like (especially considering Caviezel would go on to play Christ

in Gibson’s little flick). Given Whit’s

obvious difference in philosophy from his other soldiers, there are too many

questions about him that the film never gets around to answering, at least not

in a satisfactory manner for me. You

really want to delve into this question, Malick? I’d love to hear more about it, rather than

indulging in too many other tangents to keep straight.

The

cast is preposterously large and filled with famous actors, to the point of

actually hurting the movie. There’s

nothing that jars me out of the sort of contemplative mood Malick is so

desperately trying to cast than seeing John Travolta pop up with an ugly

moustache and horrid acting abilities.

Later on, just as I feel I’m getting into the groove of the movie, it’s

“Holy shit, that’s John Cusack! Hey,

right on, John Cusack! Oh. Right.

Movie. Supposed to be paying

attention. Crap, what’s happening now?” And then, in the denouement, where I am

supposed to be contemplating everything I’ve just seen, I’m not, actually,

reflecting on the film, but instead thinking, “Hey, George Clooney! Alright, I like George Clooney! Oh wait, no, I’m supposed to be all sad

now. Ah, who cares, go Clooney!” People talk about how characters breaking

spontaneously into song and dance distracts them in a movie musical, removes

them from the film, as it were. I know

how they feel now, because every time there was a cameo – and there are LOADS

of cameos – I fell completely out of the film.

Ultimately,

I can’t come down with a positive assessment of The Thin Red Line for

various reasons. Yes, I liked some

questions that Malick touched on, and as always, his photography of nature was

stunning (I can understand why Malick, doing WWII, would choose the South

Pacific battles over the European battles, that’s more than obvious given his

propensity for grass and forests), but it has too many marks against it. Malick is incomplete in developing his

philosophical questions because there are simply too many characters, the film

feels pretentious on more than one occasion, and, the biggest mark against it

for me, it is a Modern War Movie (honestly not sure how I'll ever make it through Platoon). And,

though no fault of Malick’s, I just cannot stomach such films. Do I think The Thin Red Line a bad

film? No, I don’t think so, I think

there’s some good stuff there. But it is

so phenomenally NOT FOR ME that my rating cannot help but reflect my personal

tastes and peculiar issues.

Arbitrary

Rating: 5/10, mostly because, as I’ve said, I have almost no ability to sit

through graphic scenes of war violence.

I want to reiterate that this is not the same as me hating, or even

disliking, a film. I just can’t watch

it. There’s a difference.

I don't specifically remember any war scenes that bothered me, but I don't think that's because I am numb to them, but rather that I don't remember much about this film at all - and I saw it only 6-8 years ago. I might have also tuned the movie out by the war scenes because I remember being with it for the first hour, but then getting impatient with it, wanting it to go someplace.

ReplyDeleteI had to smile at your comment about the cast being as big as your high school.

Hee hee, thanks.

DeleteAs soon as I saw Woody Harrelson pull the pin out of the grenade, but then the grenade broke somehow, my eyes widened for a split second, then my brain went "SHUT YOUR EYES NOW!!!!! NOW NOW NOW NOW NOW YOU DO NOT WANT TO SEE WHATEVER IS COMING!!!"

There was an extensive bombing sequence too that I just plain didn't see. No thanks, not for me.

That's the thing about this whole 1001 movies journey. I'm going to be forced to watch films that will hurt me. If closing my eyes for a fraction of the film helps me get through the movie, then I'm willing to lose that fraction in order to see the flick.

It's definitely a bit meandering. I was ready for it to be over by the end of the evening, for sure.

Apocalypse Now is a really good philosophical war movie.

ReplyDeleteover here replica louis vuitton bags these details gucci replica handbags pop over to this web-site bags replica gucci

ReplyDelete