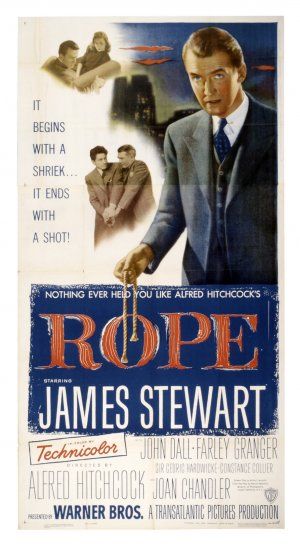

Rope

1948

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Starring: James Stewart, Farley Granger, John Dall

Rope is alternately absolute classic Hitchcock, and very novel Hitchcock. Famous (or, perhaps, infamous) as being shot in only ten takes, this is a fact that sometimes seems to overwhelm the story itself. While being an exercise in a novel technique for presenting the story, Hitchcock plays with his classic themes of suspense and psychological battles, all while peppering black humor throughout.

The film opens with the murder by strangulation (using rope, of course) of David (Dick Hogan) by Phillip (Granger) and Brandon (Dall), David’s school friends. Phillip is horrified by what he’s done, but Brandon is pleased. It appears they committed the murder in order to see if they could, and David was deemed disposable. After hiding David’s body in a large chest, they begin to prepare for a dinner party attended by David’s friends and family. Brandon is so smug, he even serves the food off of the chest in question. But when Rupert Cadell (Stewart), an old teacher of theirs, shows up at the party as well, he shrewdly starts to deduce what Phillip and Brandon have done.

The story, a fictionalized version of the infamous Leopold and Loeb murder, clearly would have appealed to Hitchcock. Considering the main running gag in Hitchcock’s earlier Shadow of a Doubt (1943) concerns two men constantly babbling about how they could commit the “perfect murder,” we seem to have a natural evolution in Hitch’s work. Instead of merely talking about it, Brandon and Phillip actually perform it, and Hitchcock examines the fallout of committing the “perfect murder.”

|

| Jimmy knows what's going on. He always knows. |

About half of the narrative is concerned with the dinner party thrown just above David’s corpse, and Hitchcock manages to keep David front and center, despite his absence. Characters constantly discuss his absence, and when they’re not talking about David, they are making allusions to death and murder. “I could strangle you,” quips David’s fiancée to Brandon. Brandon tells an anecdote about Phillip strangling chickens in the country. Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment is referenced by a guest. In fact, the discussion seems so casually morbid that by the time Rupert Cadell has a monologue about the usefulness of “controlled” murder of others by the Nietzchean supermen, it seems to fit perfectly within the conversation we have hitherto observed. Brandon’s glee in committing a murder and arrogantly throwing a dinner party before disposing of the body echoes Hitchcock’s giddiness in constantly ramping up the tension and gallows humor of the film.

The best part of the narrative, however, is the relationship and conversation between the three leads. Phillip’s nervous unraveling, Brandon’s arrogance, and Rupert’s shrewd deductive reasoning is where the film is most successful. It’s delightful, watching Stewart as Rupert slowly piece it all together, but then again, Jimmy Stewart is delightful in pretty much anything. Although I’ve never thought Farley Granger was a particularly gifted actor, he reasonably carries his role as weakling Phillip, getting more and more high strung as the story progresses. John Dall is pitch perfect as arrogant Brandon, trying to control everything and everyone around him, taking the idea of the Super Man a bit too seriously. When the film isn’t focused on these three, it is less successful. A side story involves David’s fiancée Janet and her former boyfriend Kenneth. These conversations, although keeping the focus on David and his absence, nonetheless drag the film down. David’s father and his especially silly aunt are amusing, but cheapen the overall effect.

The film is sly in its sexuality, calmly and quietly insinuating a fairly clear relationship between Phillip and Brandon. They live in the same apartment, discuss vacations from their past that they took together, and mention several times their plans to go away for the weekend to a place upstate. Furthermore, there is a marked physicality between them; they stand very close to one another, mirror each other’s movements (especially noticeable in a scene at the beginning of the dinner party where each are half seated in the same peculiar manner), and feel very comfortable touching one another. You can ignore it if you want to, but don’t tell me that the noises of relief and triumph that Brandon makes after killing David, and then later at the end of his dinner party, don’t sound more than vaguely orgasmic to you. Furthermore, Rupert Cadell seems not so sexually innocent himself. He jokes about marrying the maid, but seems to have an almost preternatural understanding of both Phillip and Brandon. Just what was his relationship with these two when they were all under the same roof at prep school together? I wonder.

I’ll now turn over to the technical aspects of Rope, those which make it famous. Hitchcock wanted to experiment with long takes, and what I find most impressive is that he produced a completely commercial and entertaining movie using avant garde cinematic techniques. Honestly, if you didn’t know that this film was shot in only ten takes, you might not even notice. That, to me, is the genius of the technique in Rope. Hitchcock doesn’t draw any gaudy attention to his long takes. They seamlessly melt away. By blending close-ups, zooms, and tracking shots into the film, we are never watching one long, boring, static take. The camera is fluid and mobile, albeit it slightly awkward when it has to traverse three rooms quickly (Steadicam had yet to be invented, and, well, it shows). The slow dimming of the lights outside the window, the entry and exit of the guests, all serve as essentially detractors from the flashy technique. Which amazes me, frankly, because Hitchcock loved flashy. You’d think that if he brazenly shot a film in as few takes as possible (they were limited by how much film stock could fit in the camera), he’d want to draw attention to the long takes. I don’t think he does.

The finale of the film is perhaps, technically speaking, the best part of the film. Hitchcock dims the lights outside, making it night in the city, and we suddenly have the appearance of the flashing neon sign next door to Phillip and Brandon’s apartment. It alternately flashes white, red, and green. When the emotions are all coming to a head, when Rupert finally makes his move, the apartment is bathed in angry red, sickly green, and illuminating white. The final shot of the film uses sound effects, and sound effects only, to signal the end of the evening, in a remarkably effective manner. Hitchcock wasn’t just a great storyteller, he also completely understood the technical tools at his disposal to tell his story in the most captivating way possible. He really plays with traditional film techniques, and it’s so much fun to watch.

Is Rope my favorite Hitchcock movie? No, and I’m not sure if it would quite make a top 5. But it’s a great deal of fun, contains some brilliant technique, and manages to be both experimental and extremely commercial, all at once. Plus Jimmy Stewart is always watchable - always.

Arbitrary Rating: 8/10

My opinion on this one is about the same as yours. Rope is a technical marvel and vastly entertaining. It might sneak into my top-5 for him, but if it did, it would be at the bottom. That says more about how good Hitchcock was when he was really on then it does about this film, though. Done by most other directors, it would be at or near the top for them.

ReplyDeleteI love both John Dall and Farley Granger in this. They're such a great counterpoint to each other, and their relationship is one of the best things about it.

Oh, Dall and Granger (and Stewart) make the film work. And Hitchcock had to have known that, that he couldn't experiment so successfully unless he had slam dunk performances from his actors.

DeleteReally good point about Hitchcock. Something else indeed.

Good review, especially the points about directors sometimes overwhelming the movie with their attempts to call attention to themselves through the use of various techniques. My personal most-hated one is Shakycam. I agree that Hitchcock does not do this. I did know of the long takes before watching it, and it first I *was* paying attention to it, but after 2-3 takes I finally stopped doing that and got caught up in the movie. Honestly, if I find myself watching things other than the story and characters then it usually means that the movie is not that good to me, no matter how great the filming techniques may be.

ReplyDeleteShakycam is really obnoxious, I agree. Not all ostentation is bad, but when the story/entertainment value suffers because of it, then, well, perhaps the filmmaker should have focused on other things.

DeleteI do not think this was a movie about the "perfect murder". Oh, it is morbid alright, but I see it as a homosexual love triangle. The entire affair this evening is Brandon's attempt at impressing Rupert that he is sufficiently übermench for him. It is subtle and subversive to use a murder mystery as a surface to this story, but otherwise he probably could not get away with it.

ReplyDeleteI agree that Hitchcock is rather subdued about his technique in this film. The objective is clearly to make us feel as if we are there, forced to watch this story in realtime and in that I think he is successful. I am just sorry that the technique after all ran away with all the attention. It is merely a tool to tell an extraordinary story.

authentic jordans

ReplyDeletehttp://www.raybanglasses.in.net

http://www.cheapauthenticjordans.us.com

longchamp uk

http://www.tiffanyandcojewellery.us.com

cheap mlb jerseys

adidas neo shoes

longchamp bags

http://www.kobebasketballshoes.us.com

jordans for cheap