Thursday, November 15, 2012

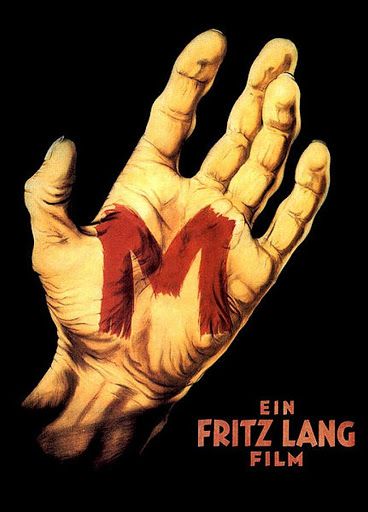

M

M

1931

Director: Fritz Lang

Starring: Peter Lorre, Otto Wernicke, Gustaf Grundgens

It took a few years for sound technology to really find its footing. While talking (and singing) in films hit the big time with The Jazz Singer in 1927, other common sound uses that we expect today – like soundtrack music – would take several years to catch on. It’s interesting watching movies from the first seven or eight years of sound technology because of this; what they use, what they lack, primitive sound technology. At the same time, films were still relatively young, and the stories they were telling were not always the most sophisticated. Each of these considerations makes M stand out that much more from its early sound counterparts. It tells a gripping and morally layered story, using sound in a smart way to further the narrative through the use of voice over for one of the first times in film, and using a piece of music to signify a certain act.

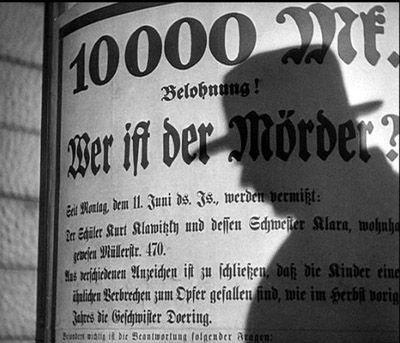

A murderer is on the loose in a German city. He kidnaps young children off the street, molests them, then kills them. The police, headed by Inspector Lohmann (Wernicke) are flabbergasted and frustrated; their investigations are proving fruitless, so they decide to perform a massive crackdown on all criminal activity. This causes the criminal underworld a great deal of inconvenience, so they, headed by mastermind Schranker (Grundgens) decide to take matters into their own hands. Just as the police begin to hone in on our psychopath (Lorre), the criminals too discover his identity. Getting their hands on him first, Hans Beckert is put on trial by the criminal underworld to answer for his sins.

The thought that was constantly racing through my head when I watched M again recently was just how much better it is than the early gangster film counterparts made in America at the same time period. Sure, Cagney and Robinson are great in The Public Enemy and Little Caesar, also made in 1931, but the previous films are overly simplistic of the criminal life. They feel tired and dated, although they are buoyed by iconic performances. Meanwhile, Lang tackles a similar genre but manages to find lasting success with how he approaches his tale. Interestingly, he goes with not a gangster but a psychopath, and a pretty terrible psychopath at that. A monster who kidnaps, molests, and kills little kids? Christ almighty, that’s horrible!

I always feel hesitant declaring that any film is “the first” to do something, mostly because I am well aware that my film education is sorely lacking and I expect someone to come at me with “didn’t you know about this earlier movie that did this too?” But I will go out on a limb and say that M is the *best* early example of a police procedural. M is divided into two distinct halves. In the first hour of the film, we follow the police in their investigation; in the second, we follow the criminals as they trap Beckert and try him. The first hour of the film is so well done, so gripping in its portrayal of the search for the killer, that I attest it could be easily adapted to any episode of any one of the tens of police procedural shows that are on the air on television right now. Make a few small changes, and this could be an episode of CSI that you’re watching. Or Bones, or NCIS, or Castle. The only major difference is the lack of computers; other than that, we have the same sort of careful attention to forensic details, the questioning of everyone who could possibly be involved, the investigation of the living quarters but missing the key clue, then the return to the living quarters and finding the key clue. There are so many classic procedural tropes established in M, it’s almost unfair to realize that in one fell swoop, the stereotypical scenario of a good chunk of the scripted dramas on television today was established.

Fritz Lang’s directing is amazing; I suppose it’s to be expected from such a famous director. He cleverly intercuts scenes of the police tracking down Beckert with the criminals also tracking down Beckert, drawing clear parallels between “regular” society and the criminal shadow society. In a staggering tracking shot that isn’t discussed nearly as much as it deserves, Lang moves the camera through windows, doors, and walls as we go through the criminal hideout. It’s a very early precursor of the Goodfellas Copacabana shot, but all that much more impressive when you consider the technology that Lang was lacking. I’m still not entirely certain how he did it.

All of this, however, deals with the first half of the film. It is the second half where we are treated to a wonderfully complex sociological debate. Beckert begins to make more appearances in the second half – he is notably absent from the first hour of the film, appearing in only a handful of scenes and never speaking any lines. We know, however, that he is our killer. Lorre’s performance is sad and frightening and horrible and pathetic; a real career defining turn. He is constantly battling with himself and his impulses. His Beckert does not want to kill, but he is too compelled to do it. He has to give in. In one of the saddest sequences of the film, we watch Beckert try to control his urges and fail miserably. It is this that makes M stand apart from a psychological angle. As awful as it is, we sympathize, even just a little, with Beckert. We don’t want him to do it, he doesn’t want to do it, and when he fails to fight his urges, we weep for him. It is this argument that is Beckert’s pathetic defense against the criminal tribune. He cries out at them that while they have chosen a life of crime, he never had such a choice; he MUST commit his acts. Lorre is so sad, so animalistic in his yells of agony here, it’s mesmerizing. Yes indeed, Lang has created a sympathetic child molester. What the hell?!?!?

Flat out, M stands up. It has legs. The forensic investigation is fascinating and well done, and will connect with modern TV audiences. Lorre’s performance is striking and sad and incredibly memorable. And really, you won’t ever hear Grieg’s “In the Hall of the Mountain King” in the same way again.

Arbitrary Rating: 9/10

Labels:

1001 movies,

1930s,

1931,

9 out of 10,

foreign,

german,

lang,

M

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

You hit the nail on the head in regards to Lorre's character being simultaneously horrible and somewhat sympathetic.

ReplyDeleteI *will* go out on a limb and say that this film has the most smoking in it. :-)

Yeah, you start coughing just watching it :-)

DeleteY'know, I didn't even notice the smoking. I guess I just take it for granted that older movies have more smoking than a Wednesday night bingo parlor.

DeleteLorre makes the film for me, taking it from "standard" to "extraordinary."

I entirely agree with you. Add colours and this could be a recent movie. I love your comparison to CSI and the likes, but this story is far ahead of those generic episodials in complexity. For all the zillions of crime shows I have seen I have never seen anything like M elsewhere.

ReplyDeleteAnd goddammit this is from 1931!!!

You're absolutely right - the police procedural bit is standard, but you're right, the story - the sympathy towards Peter Lorre - is far more complex than we ever get on those shows.

DeleteI know, I can't believe this movie was made in 1931 either. It's years ahead of its contemporaries, that's for sure!