The Night of the Hunter

1955

Director: Charles Laughton

Starring: Robert Mitchum, Shelley Winters, Lillian Gish, Billy Chapin

The Night of the Hunter is many things. One of Robert Mitchum’s finest and most iconic performances, the phenomenal sole directorial work of Charles Laughton, some of the best work of cinematographer Stanley Cortez, and a children’s version of a film noir. It is that last point that keeps me coming back to this movie for more.

Preacher Harry Powell (Mitchum) is a serial killer masquerading through 1930s West Virginia as a man of God. After sharing a jail cell with Ben Harper (Peter Graves of Airplane! infamy), he hears of Harper’s hidden $10,000. After Harper is hung, Powell makes a move on the rest of the Harper family, seducing widow Willa Harper (Winters), but he cannot win over young John Harper (Chapin). John knows where his father hid the money, and he’s not telling. He doesn’t trust the preacher. When Powell’s serial killing inevitably claims his mother as his next victim, John grabs his little sister Pearl and runs away down the river, eventually finding their way to the safety of Rachel Cooper (Gish), a woman with a will of steel and a shotgun that she’s not afraid to use. Powell tracks down the children, but must face Rachel first.

In terms of photography, I’m really not certain how this film could be bettered. Some of the most phenomenal work with light and shadow is found within the 93 minute running time. The shot of Willa’s bedroom, illuminated like a chapel with the slanted ceilings, or the underwater beauty of Willa’s hair mingling with the seaweed. Or, then, the careful lighting of Rachel with the shotgun and Harry Powell on the tree stump. Or anything that takes place on the journey of the children. This film is gorgeous. The cinematographer, Stanley Cortez, arguably produces his finest work, and he knew it, too. Cortez said that the only two directors who truly understood light, “that incredible thing that cannot be described,” were Orson Welles (whom Cortez worked with on The Magnificent Ambersons) and Charles Laughton. For Laughton to be mentioned in the same breath as Welles is indicative of just how beautiful this film is, and the fact that I don’t disagree with Cortez’s assessment of Laughton’s skills is significant (all of which makes me mourn the fact that Laughton abandoned directing). This is a stunning film.

The fact that the film has amazing visuals is certainly a huge help, but what keeps me coming back for more is the fairy tale theme of the narrative. The term “fairy tale” has been methodically corrupted in the last seventy years or so to fall in line with the Disney Studio’s concept of pretty pink princesses who do nothing and expect their Prince Charming to appear and shower them with shoes and houses and trust funds galore. As a child, I still distinctly remember reading a hardcover illustrated version of “Snow White” and not understanding why it was different from the Disney movie; I actually believed that Disney had written the story himself. Once I realized my mistake, I started to delve into the classic, original stories by the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen. I had The Red Fairy Book, The Yellow Fairy Book, and The Purple Fairy Book, and I loved Faerie Tale Theatre.

One of the things that attracted me so strongly to fairy tales in my youth was the dark, dangerous quality to them. They were full of beautiful imagery, but this imagery was of both the light and dark quality. There were crystalline trees, but also forbidding forests. There were beautiful princesses, but also stepsisters who cut off their own ankles and toes in order to fit into a shoe (and a prince who was too dumb to notice the bleeding until a little bird drew his attention to it… what a jackass). The melding of such horrid ideas with “happily ever after” was a big draw for me, but Disney has scaled waaaaaaaay back on the “frightening” aspect of the original stories. Ladies and gentlemen, “The Little Mermaid” does not. end. well. Ariel dies and gets turned into sea foam, never living out her life with her prince. Check the story.

|

| Creepiest duet ever? I think so. |

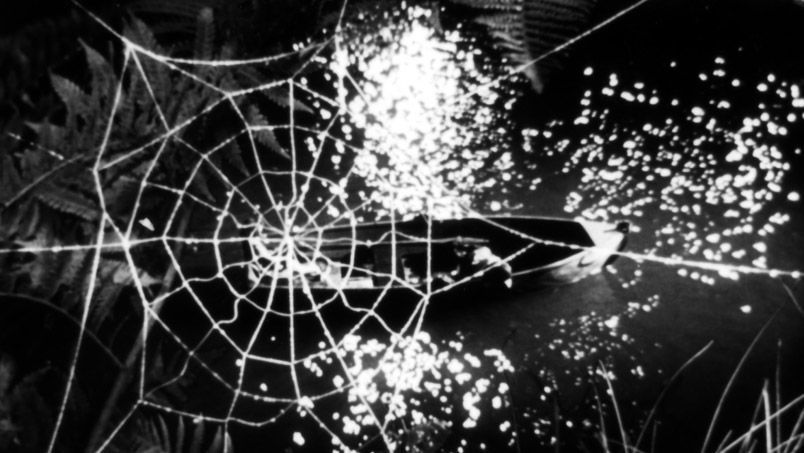

The journey of John and Pearl down the river as they escape Powell is possibly my favorite sequence from the film, mostly because it epitomizes everything that is truly otherworldly about this movie. The photography, often with very large creatures in the foreground with John and Pearl in their boat in the background, draws our attention to the natural world that surrounds the children. We see a huge toad, a spider, and rabbits. I remember reading an article once that mentioned what these specific animals signify, but I can’t find it anymore. The moonlight, brighter than any moonlight I’ve ever seen, sets the river sparkling around them, as if they are completely aglow. When John and Pearl hide in a farm, however, we see a very small Powell on his horse on the horizon; evil is constantly tracking them, never tiring, never sleeping (as John notes).

In addition to the rather childlike quality of the fairy tale, there are many rather blatant references to sex in this movie. Icey Spoon, the old woman who runs the ice cream parlor, is constantly blathering on to Willa about how she needs a husband, and then runs her mouth at the picnic about how no self-respecting wife actually desires sex. Willa shames herself for wanting to sleep with her new husband. One of Rachel’s other charges, the adolescent Ruby, sneaks into town for illicit dates with boys. And Harry himself seems not motivated by greed, but by the incapacity to control his own sexual urges. We see him at a striptease, glacially watching the vulgar dance. He reaches into his pocket to fondle his knife. No, his actual pocket knife, which then thrusts out of his pocket. I mean, how much more obvious can you get?!?!?

I’ve seen this movie several times now, and I’ve stopped seeing it as an attempt to tell a realistic story. It’s not a realistic story. The photography is heightened and exaggerated, the situations become manic and over the top, and everything is played out to the extreme. This is a fable, a fairy tale, not cinéma véritée. And Robert Mitchum – how could I not have mentioned him yet? This is the role of a lifetime for him. He is wonderful, the story is wonderful, the shots are wonderful… this is an amazing film.

Arbitrary Rating: 10/10

For me, there is no better shot and no better moment than when we learn of Willa's fate. It's just so incredibly eerie and strangely beautiful at the same time. For me, you can stop and start any discussion of the genius of this film there.

ReplyDeletePearl drags it down for me--she drives me to distraction. But everything else is basically flawless, particularly the menacing Mitchum.

I love that shot... it's, as you say, strangely beautiful. What a powerful moment.

DeleteYeah, I concede the Pearl point. I liked how, in your review, you called her a Kewpie doll - you're absolutely right. What is it about child actors from the thirties/forties/fifties? I want to punch Margaret O'Brien every time I see her in a movie.

One of the all time great screen villains, clothed in religion, no less.

ReplyDeleteI heartily endorse screen villains being clothed in religion, since it mirrors my worldview that most off-screen villains are similarly attired.

DeleteNot disagreeing with anything being said here! Organized religion has long been problematic to me, so perhaps one of the reasons I respond so well to this movie is, as Chip notes, the showing of evil being perpetrated in the name of religion.

DeleteMitchum is so good and so creepy.

I can't argue with any of your points about the exemplary cinematography, but in the end that wasn't enough to win me over. There were a lot of other things that underwhelmed me and dragged down the whole movie. Mainly the characters and the plot. But I really appreciate your perspective in casting the film in fairytale terms. I hadn't considered that myself but I think it's got some serious merit. Maybe not enough to completely redeem the movie for me, but good food for thought while contemplating the aspects that didn't work for me.

ReplyDeleteSunny D

Hey, fair enough - I think we all have highly touted films that just don't work for us (I have not yet posted my tirade about how Gone With the Wind is four hours of my life I'm never getting back). At the very least, I'm happy I could present a different perspective for the film that gives you something to think about!

Deleteadidas nmd

ReplyDeleteadidas nmd

michael kors handbags

hermes belts for men

http://www.cheapairjordan.uk

nike roshe uk

nfl jerseys from china

kobe shoes

michael kors outlet

fitflops outlet

air jordans

ReplyDeleteyeezys

ferragamo belt

michael kors

balenciaga speed

yeezy boost 350

kyrie 6

timberland

hermes handbags bag

cheap jordans