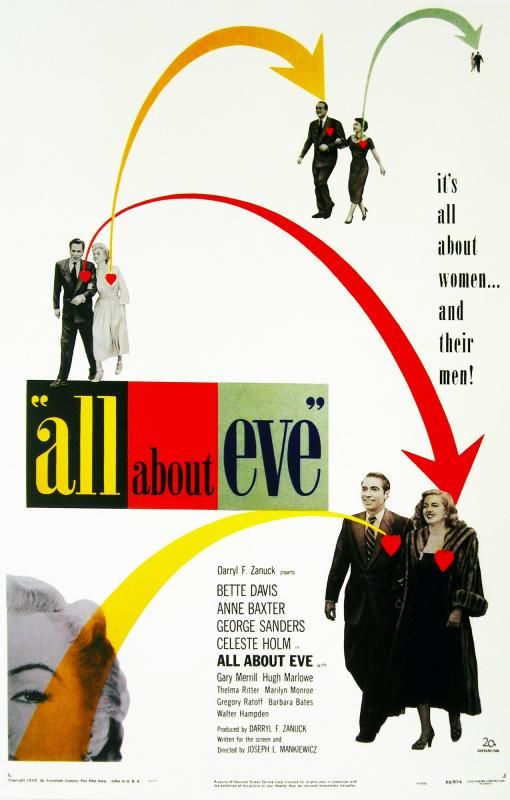

All

About Eve

1950

Director: Joseph L. Mankiewicz

Starring: Bette Davis, Anne Baxter,

George Sanders, Celeste Holm, Thelma Ritter

Some

movies are famous because they come from a certain director. Some are famous because they tell a

fascinating story, and others are famous because of gorgeous

cinematography. While All

About Eve’s director is certainly famous enough, and it’s story interesting

enough, I don’t think this is where it gets its power from. No, All About Eve’s power comes directly

from two sources: smart writing and wicked acting, and here, the two go hand in

hand. This entire movie is about

characters, about winding them up and watching them interact with each

other. And it’s just phenomenal on that

score.

Margo

(Davis) is a famous theater actress with a tight knit group of friends,

including Karen (Holm), and her assistant Birdie (Ritter). One night, Karen sees a young woman, Eve

(Baxter), who has never missed a performance of Margo’s latest show and takes

her backstage to meet her idol. What

inevitably unfolds is Eve’s wrangling her way into Margo’s life, slowly and

insidiously trying to not merely follow in Margo’s footsteps, but actually take

over her life. She takes Margo’s place

on the stage and tries to steal her boyfriend away. But even Eve meets her match as soon as she

comes up against oily theater critic Addison DeWitt (Sanders).

The

opening scene sets up the entire plot, even letting us know, more or less, what

will happen, and certainly establishes the vicious attitude of the film. We are treated to George Sanders’ biting voiceover

as he sarcastically points out, as only Sanders can, the foibles of nearly

every character in the room. Our first

major character introduction, besides Addison DeWitt, is Karen, and Holm is

ever so good in keeping a placid façade that nonetheless cannot hide her

disgust. We then have a close up on

Margo, and here, even more so than Holm, Davis is barely containing a sense of

hatred. Right from the moment the flag

drops, All About Eve is vicious and underhanded, and it’s bloody

fantastic. Although I wouldn’t call All

About Eve a film noir, it may be likened to a female noir, at least in

terms of character interaction. There

are no guns and no death and certainly no shadowy lighting, but it has a bit of

noir attitude. It’s transplanted from

the world of crime to the world of the theater; we get to watch people tear

each other apart not with bullets but words and attitudes. Again, I would never classify All

About Eve as a film noir, but I do believe my attraction to this film

is related to my attraction for classic noir.

|

| Plus Marilyn Monroe. What more could you need? |

What’s

key here is that we know from the get go, from before the first backstage scene

with Margo’s crew, that Eve is acting.

We can tell from how Eve bows sycophantically when she is accepting the

Sarah Siddons award in the opening scene that nothing about her is genuine. The fact that Karen and Margo do not applaud

is merely confirmation, not a revelation.

When, ten minutes later, she is regaling us with her tale of hard luck

and woe, we don’t buy it for a second.

This turns the focus in this scene not to Eve, but to Margo. We watch with disbelief as Margo swallows

every damn word Eve feeds her.

Personally, I love it when Birdie immediately calls Eve out, how Birdie

can see through her shenanigans immediately.

That’s key, because it gets us thinking about the distinctions between

Margo and Birdie, why Margo buys it but Birdie doesn’t. Eve’s ploy would never work were it not for

Margo and her ego, and this first meeting sets that up perfectly. Birdie is utterly without ego, a sharpshooter

who simply calls it like she sees it. Margo,

on the other hand, while kind and loyal, is also full of herself, and her ego

is too well-stroked by Eve to allow her to see clearly, and that is her

downfall.

Davis

is, naturally, fantastic in this, one of her most iconic roles. If it were any other actress playing Margo, I

would use the term “brave” to characterize this performance, but because it is

Davis I will say it is “par for the course.”

“Brave” becomes a redundant term when discussing La Davis; she was an

actress full of fearlessness. In

particular, I am astounded at the continual references to age in All

About Eve. Margo seems to

comment nearly continually about the age of people around her, knowing full

well how young Eve is compared to her.

Margo makes jokes about her age, which is never explicitly revealed, but

these jokes always betray a sensitivity towards aging. Margo realizes that she is too old to play

the romantic heroine anymore, and as an actress, what is she now to do? Her role is changing and she does not want to

simply accept her movement to less gracious roles, but sadly, she is forced to

do exactly that. For Davis’ part, she

was 42 when she played Margo, and she looks every day of it, perhaps even

older. There are bags under her eyes and

creases in her forehead, and her jaw sags ever so slightly. How sad that I find this unusual, to see a

middle-aged woman playing a middle-aged woman and looking exactly like a

middle-aged woman, and what a comment on Hollywood. What roles are there for an actress above a

certain age? With that in mind, it’s

stunning that both All About Eve and Sunset Boulevard were released in

the same year, as both films tackle the issue of the marginality of the aging

woman, but not men. As Margo says,

“Bill’s thirty-two. He looks thirty-two. He looked it five years ago, he’ll look it

twenty years from now. I hate men.” I get the feeling that if we locked both

Margo Channing and Norma Desmond in a room together, they would either claw

each other’s eyes out or get massively drunk together while swapping anti-aging

tips.

Several

years ago, I saw All About Eve at the Dryden.

I had seen it before on DVD, but I rarely pass up the chance to see a

film on the big screen, as I am all too aware that the right (or wrong) setting

can alter the effect of a film. What I

did not know, as I settled into my regular seat, was that All About Eve is an

iconic film in the gay community. My

ignorance was quickly wiped away, as it became very apparent very fast that

there a large number of, how shall I say this, vocal fans of the film in the

audience. What resulted from this was an

absolutely uproarious evening, with booing and hissing at Eve and cheers

aplenty for Margo’s bitchiness. The

experience gave me an entirely new respect for the sheer entertainment factor

of this film, and it was one I’m glad I got to experience.

I’ve

returned every year or so to All About Eve, and every time I do,

it keeps getting better. As I age,

although I don’t consider myself old, I find myself enjoying it more. There’s a great deal going on in All

About Eve (and I didn’t even get to mention how much I adore George

Sanders!), and multiple watches simply give me more to think about. The great films bear up to repeated

viewings. All About Eve is

undoubtedly a great film.

Arbitrary

Rating: 9/10