To

Kill a Mockingbird

1962

Director: Robert Mulligan

Starring: Gregory Peck, Brock Peters,

Mary Badham, Philip Alford

I’ll

start this one with a bit of a shocker: I’ve never read the novel To Kill a

Mockingbird. Somehow, in my high

school years, I managed to miss that one particular piece of definitive

American fiction. Perhaps that helps me,

though, in examining the film; I’m untainted by what is usually perceived as a

negative experience of “having to read” something for school.

Atticus

Finch (Peck) is a small town country lawyer in 1930s Alabama. His two young children, Jem (Alford) and

Scout (Badham) watch their father with reverence and awe as they go about their

typical childhood shenanigans. Things

get serious, though, when Atticus is brought on to defend Tom Robinson

(Peters), a black man, against an unfounded rape charge of a white woman,

bringing in issues of race, class, and justice.

Although

I haven’t read the book, I can say that the film of To Kill a Mockingbird

seems a very potent adaptation. It works

well onscreen, with clearly drawn characters and a distinct narrative structure

to the story, along with some fairly heavy-hitting social issues that manage to

sneak in after the movie has lulled you into a sense of complacency. As is the case with most films that focus on

childhood recollections, there are many small episodes and no real overarching

narrative thread to the film; however, the characters, especially Atticus, are

strong enough to tie everything together in a satisfactory manner.

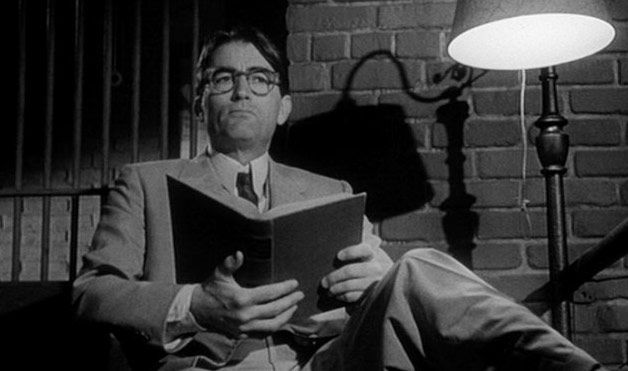

Atticus

Finch, as portrayed by Peck, is easily the bedrock of the film. It’s easy to see why the AFI named Finch the

number one Movie Hero of all time.

Finch’s heroism is made all the more powerful by the fact that it’s less

blatant and more troubled than most typical do-gooders. Peck, as Finch, is quiet but self-assured,

calm but passionate, and he even he can be pushed too far as seen in an utterly

wrenching scene late in the film. My

favorite aspect of his performance is how understated it is; there’s a lot of

subtlety in Atticus. I haven’t exactly

exhausted all of Gregory Peck’s filmography, but after revisiting him in this

film, I’d be hard-pressed to name a better performance of his. Unlike many other actors of his generation,

(like Cary Grant) I don’t see this role as Peck simply playing some aspect of

Peck. No, this is a fully realized

performance; this is not Gregory Peck, this is Atticus Finch.

Movies

that focus on child actors tend to live or die by the performances of the

children. Scout and Jem are solid

performances; not the best child actors I’ve ever seen, but solid. Alford as Jem is fairly typical child actor

performance, solid but not amazing, but Badham as Scout was very good. In terms of speaking the lines, she was

essentially like any other child actor (re: acceptable), but it was her

physicality that set her apart. Badham’s

Scout is all tetchy movements, elbows and knees, squints and sly smiles that

she can’t seem to help. The scene where

Scout is reading in bed with Atticus is a perfect example; Badham doesn’t have

extensive lines, but it’s the way she handles the book, the way she stretches,

the way she touches the watch with eager, awkward fingers that just feels

perfect. Intentional or not, these are

the marks of reality and helped make her performance in particular work so well

for me.

To

Kill a Mockingbird

has been described as a gothic film in terms of its approach to the mysterious

beliefs that children concoct for themselves.

Removing the courthouse drama episode from the film (which is discussed

below), there is definitely a dark fairy tale tone to the story that puts To

Kill a Mockingbird in the same family as Night of the Hunter. The difference of the father figure sets

these two films apart – one pure evil, one pure goodness – but the tones are

similar. The fright of Boo Radley’s

house, the wonder at discovering the trinkets in the tree, the invented

stories, and the terror of the final battle in the woods; they all have an air

of surrealism to them, a dark magic that nicely coincides with traditional (re:

not Disney) fairy tales, one often helped along by terrific camerawork.

To

Kill a Mockingbird

seems to me to represent a fundamental shift in American filmmaking. Although the late sixties are typically seen as

the focal point for the change from “Classic Hollywood” to “Modern Hollywood,”

due to, in no small part, the eventual influence of the French New Wave, the

pumps had to be primed in order to accept that change. To Kill a Mockingbird is a film that

got Hollywood ready to change. The

episodes that deal with the gothic children’s tales of the original story are

presented in a typical “Classic Hollywood” manner, but it is the sneakiness of

the story suddenly warping into a wretched one of racism, bigotry, and

intolerance, one that has more than one powerful punch to the stomach in store

for you, that provides glimpses into the “Modern Hollywood” that would come a

few years down the road. The courthouse

drama episode, easily the most memorable one of the film, stands head and

shoulders above the rest of the story and is surprisingly fresh and gripping. It doesn’t feel outdated in the least. It is still potent and, unfortunately, still relevant. There are certain expectations from a

courthouse drama, and To Kill a Mockingbird manages to

throw most of them on their head, a major reason why this film works as well as

it does and why it sets the path for the new means of filmmaking that

followed. This aspect of the story is

incredibly courageous in what it dared to do and show in 1960s America, a

culture in the midst of a civil rights flashpoint.

Distinctly

episodic in nature, To Kill a Mockingbird is defined by its characters and its

performances, and it is strong in both.

Although not a particular favorite of mine, Peck as Finch is fantastic

and in my recent rewatch, I found myself rather unexpectedly in tears several

times. This is a film that rightly

deserves to be remembered and passed on.

Arbitrary

Rating: 8/10

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteI was assigned To Kill a Mockingbird to read in eighth grade. It's pretty brilliant - Harper Lee is a national treasure. To this day I can remember how my English teacher used to gush about the novel: "Not a word is wasted." It's interesting to me that the movie feels so episodic to you when I consider To Kill a Mockingbird a pretty unified story about Scout making the transition from being a little girl to beginning the painful process of growing up. The plot might be all over the place but the thematic throughline is strong. Of course, I watched the movie in class right after we had all finished reading and discussing the novel, so maybe I was guided toward seeing things that way.

ReplyDeleteAnyway, if you can make the time, read it! I can't possibly recommend the original novel enough.

- Sunny D

It's one of those books that I look back on my [very good] public school education and wonder how on EARTH I never read it for a class. It definitely feels like a gap to me. I suppose there's only one way for me to fix that, huh - get off my butt and get to my library and check out a book (rather than a DVD) for a change!

DeleteI see the film as episodic, definitely, but as you mention, with themes that run consistently throughout.

adidas nmd uk

ReplyDeleteskechers shoes

air jordan retro

ralph lauren online

yeezy shoes

michael kors uk

ralph lauren online,cheap ralph lauren

adidas tubular runner

adidas tubular sale

hermes belt for sale