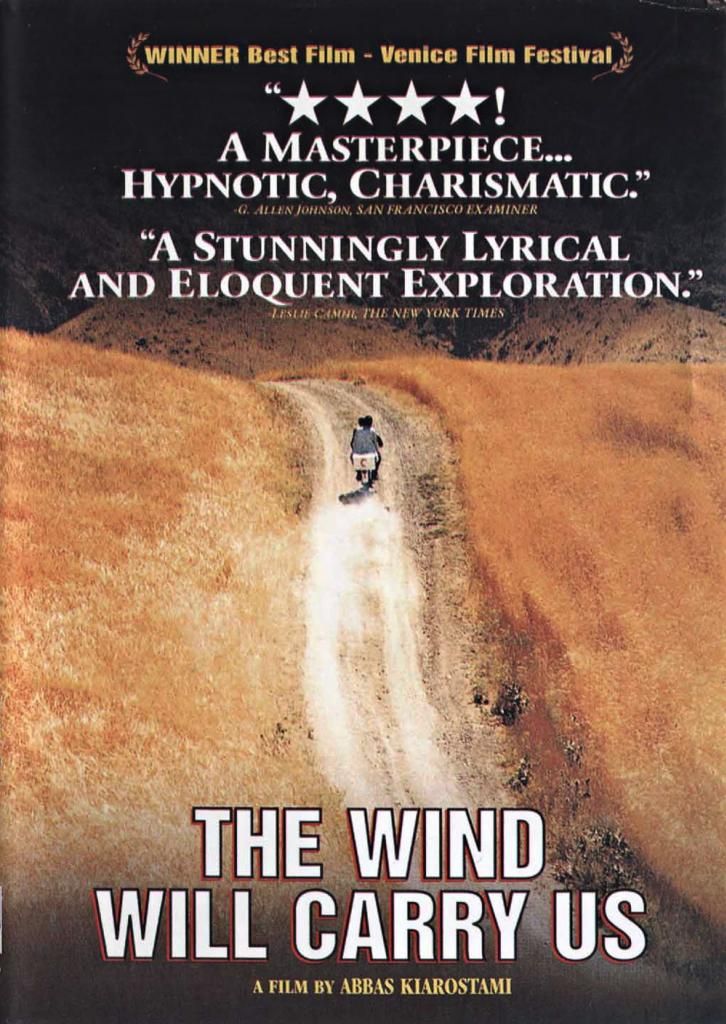

The

Wind Will Carry Us

1999

Director: Abbas Kiarostami

Starring: Behzad Dorani

I

can’t help myself – the more I see Kiarostami’s work, the more I’m fascinated

by it. Part of me doesn’t really

understand why. The latest of his I’ve

seen, The Wind Will Carry Us is, on the surface, frustratingly

meandering, with no clear sense of purpose – or, for that matter, narrative. Usually that sort of movie drives me

nuts. But my goodness, take a moment to

peel back the outer layer, and suddenly this new world opens before your eyes,

one with meaning and poignancy and symbolism and, well, just so much more to

offer than simple “plot.”

The

story – which is not the focus of the film, to be very clear – is about a man

from the city (Dorani) who comes with a small crew to a small village in the

country. His purpose there is a bit of a

mystery, and he tells everyone he is an engineer. He befriends a small boy and keeps asking him

questions about the boy’s dying grandmother.

He keeps getting cell phone calls, but has to drive his Jeep up the side

of a hill in order to answer the call.

He drinks tea, borrows milk, chats with his neighbor, enjoys the

hospitality of the townspeople… and, well, that’s about it.

Usually

films like this infuriate me. Nothing

happens. If anyone reading this is

stunned by my enjoyment of such a film, trust me, I’m a little in shock myself. But with Kiarostami, he does it in such a way

as to draw me in, to hypnotize me, to get me thinking about, well, lots of

stuff.

The

incredibly simple story raises big questions: city/technology versus country,

the ethics of being a “good” person, life and death, and even gender

issues. Behzad Dorani, who I’m certain

follows in the Kiarostami tradition of being a non-professional actor, is the

vessel through which nearly all of these questions are explored. There is not a single scene he isn’t in, and

very few shots in which he doesn’t appear.

Life

and death are examined on several levels, the most obvious of which is through

Behzad’s constant questioning about the health of the ill grandmother. He seems rather obsessed with her condition,

and is, in fact, anxiously awaiting her death.

He and his crew have several conversations about it, frustratingly

saying they wish they could speed up the Angel of Death. We see death fleetingly appear again towards

the end of the film when a man digging a ditch is in the hole when rocks fall

in on him. Curiously, Behzad, who seems

so obsessed with waiting for the death of sickly grandmother, rushes to the

man’s aid, calling for help from nearby visitors; his actions spare the man his

life. We hear Behzad console his parents

in a phone conversation early on; apparently, a friend of theirs has died, but

Behzad won’t be able to make it home for the funeral. The hilltop to which Behzad must drive to in

order to receive cell phone calls from his employers in the Big City is also the

village’s cemetery. He walks amongst the

grave, completely unaware that the spot that connects him to his “life” is the

same one the villagers have chosen for “death,” comically yelling at his boss

over the phone in frustration. It’s a

fascinating juxtaposition. Meanwhile,

Kiarostami shows us many depictions of the perseverance of life to contrast

with this death imagery. Behzad, in a

cruel act of irate boredom, purposely flips over a tortoise, leaving the animal

apparently helpless on its back. Behzad

walks off, angrily pleased in causing pain; however, we immediately cut back to

the tortoise to see it righting itself. Behzad’s

neighbor is a very pregnant woman; he jokes with her about how produce sown in

winter ripens in the summer. The next

scene we see, the woman is no longer pregnant, but right back to work around

the house, just carrying a small child.

The sickly grandmother remains completely offscreen, but we learn

through the film that her condition is actually improving. Farm animals run joyously rampant throughout

the village, and Kiarostami freely shows us the gorgeous landscapes that

surround the village, constantly connecting us back to nature, that ultimate

life-giver. In a significant

conversation at the end of the film, Behzad talks with a doctor who has so

little to do, he admits that he spends most of his time simply observing

nature. Behzad says that the beauty of

the next world, Heaven, is surely greater than that here on Earth, to which the

doctor replies that no one who has seen the beauty of Heaven has returned to

Earth to confirm this. The doctor then

tells Behzad what he must hear, to stop anxiously waiting for death, to enjoy

the life he is given. Stop hurtling

forward without appreciating the small things that make life worth living.

Phew. So we have, on one level, a very discreet

treatise on the meaning of life and death.

Another major issue I saw several times throughout the film was the

issue of gender roles. The only adult

men we see, other than Behzad, are very old.

This is explained by the fact that the film is set in summer, and all

the men are out in the fields farming.

This is significant, as it means that Behzad is our only representative

of “Man” in the film; even Behzad’s crew are only heard, never seen; the man in

the ditch that Behzad saves is never seen, despite the multiple conversations

Behzad has with him. Women, on the other

hand, are found everywhere. The voice on

the other end of Behzad’s phone is a woman, clearly Behzad’s boss, and she

seems to be ordering him around quite a bit.

Then there is the elderly café owner who argues vehemently that women

work just as hard as men. Behzad smiles

drolly at her, tries to take her picture, but she immediately admonishes him

and shuts him up. The pregnant woman who

gives birth then immediately returns to her household work astounds Behzad; he

cannot comprehend such a feat. Most

interesting to me was the young girl that Behzad catches running away from her

lover. He recognizes her by her dress

later when he asks her mother for milk.

Behzad descends to a small cellar to get the milk from the daughter, and

he asks her about her lover. At this

point, we have an odd combination of both conservative traditionalism and

feminist strength. The young girl does

not look Behzad in the face and will not show him hers, despite his pleas to

see her. I interpret this a few ways;

first of all, from a traditionalist standpoint, it’s possible the girl, as an

unwed sixteen year old, did not want to raise her face to a man who could be

considered a suitor. Second of all,

there is the possibility that the girl is ashamed of her actions and is hiding

for that reason. Lastly, there is also

the possibility that the girl is flat out refusing to do what a stranger is

telling her to. What would you do if a

man you didn’t know started demanding things of you? Why should she show her face? She is strong and resilient despite his

demands. During this little standoff,

Behzad actually recites poetry to her, something which pops up several times

throughout the film. The poetry is by a

modern female Iranian poet, Forough Farrokhzad, and Behzad purposely mentions

this to the girl. She is intrigued, and their

conversation turns to whether or not she could write poems as well. The female characters in this film are

surprisingly strong with wills of steel, unwilling to bend or break simply

because a man applied a little pressure to them. On the other hand, the main character of the

film, Behzad, is a rather weak man, bored and petty and a little shallow. I argue that he undergoes a degree of

redemption by the end of the film, but there’s little doubt in my mind as to

this being a profoundly pro-female film.

I

want to add at least a few comments as to the beauty of this movie. In the two previous Kiarostami films I’ve

seen, he presented me with the very dry, dusty city outskirts in Taste

of Cherry and with an incredibly lush and verdant forested hillside in Through

the Olive Trees. Here, we have

some sort of a blending of the two.

There are amber fields and dry dirt roads, but also trees and green

farmlands, all surrounded by breathtaking mountains. The village itself is alive with color. The buildings are pale, but painted with

turquoise doors and windows. The women

are dressed in vibrant colors. The sky

is blue, the walls are white, the plants are green, the road is yellow; this

entire movie jumps off the screen in its color work. Kiarostami perfectly manages to capture that

late summer evening feeling, when the sun is setting and casts its golden rays

upon everything in the heavens.

There

was a pamphlet in the DVD of this film that contained an essay by

Kiarostami. The gist of the essay was

him saying that he believes not in blindly supplying the plot to the audience

members, but in purposely leaving gaps in his films that the audience will fill

in on their own based on their individual life experiences. I just love that. So much of what I’ve seen from him is exactly

that: he presents me with something ambiguous or, in his words, with “gaps,”

and I find in myself how I interpret that situation and how I fill in the gaps. Everything I see in The Wind Will Carry Us is

based on who I am as a person; I impose myself into the film. GAD, I love Kiarostami.

In

this quiet little film about nothing, Kiarostami gives me so much to think

about. I understand if you may have

found this film frustrating and going nowhere.

Usually I’m right there with you.

Usually simple meandering films like this are a chore and a half for me

to get through. Not so in the least for

Kiarostami. Through the utter simplicity

of the repetition of daily life in a small country village, he unearths these

profound questions in my soul.

Arbitrary

Rating: 8.5/10

I liked this film, but didn't love it. Usually I hate it when a joke gets beaten to death, but I chuckled every time the guy had to drive up to the top of the hill to get better cellphone reception. I also enjoyed the countryside that was shown to us on the film.

ReplyDeleteI debated with myself on whether I should mention this next thing or not. I finally decided I would because it might help with understanding the scene where the woman wouldn't show her face.

At the time this film was made in Iran there were laws against filming women in their homes. (This has apparently been relaxed some time before A Separation was made.) As a precaution directors tended to only show little girls in their movies or to only show women out of doors. If you think about this film, almost every shot of a woman is an exterior one. The only one that is inside a structure is the one where the woman would not show her face. It was technically not a "home", but the director wasn't taking any chances and deliberately did not show her face on screen in that scene so he wouldn't get in trouble.

I remember you saying that before, and I think it does help explain Kiarostami's use of exteriors in so many of his movies. It's a great example of how a filmmaker works within their own particular restraints to still make a pretty rockin' movie.

Delete