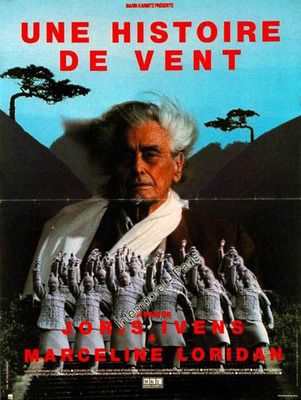

A Tale of the Wind

1988

Director: Joris Ivens

Starring: Joris Ivens

It’s very difficult to categorize this film. It’s a little bit of a documentary, but then it’s not. It’s a bit of a surrealistic film, but then it isn’t. It’s from a famous artistic director whom I’ve never heard of before. There are gorgeous shots of nature, and then completely artificial set pieces.

Experimental cinema? You betcha. But unlike obnoxious experimental films, there is a distinct sense of whimsy and magic laced throughout A Tale of the Wind that makes the sense of incomprehensibility go down that much easier.

Director Ivens plays himself – a 90-year-old filmmaker who has made movies all over the world, for many different governments. Having been an asthmatic his entire life, he says in the opening moments of the film that his goal was to film the most elusive subject of all: the wind. That is the pretext upon which the film is built. I was grateful for this; it certainly helps to provide an entry to understanding most of the film. Why am I being shown this particular stunning shot of the Chinese desert? Oh, because the wind shaped the sand dunes into these particular forms. Why am I being shown this shot of the mountains? Oh, because the wind shaped the plateaus as I’m seeing them now. Why are we seeing shots of mythic Chinese dragons? Because when they blow, they create a magical wind. Why are we listening to these weather reports? Because the weather reports are describing damage done by the wind.

|

| Yes, this is from this movie. I'm not exactly sure what it is, but it was fun, regardless. |

The “wind” aspect of the film doesn’t quite work to explain most of the film, however. In fact, my two favorite sequences had little to nothing to do with the wind.

The first of these was an absolutely joyous piece that starts with Ivens being taken to a hospital for problems with his asthma. He is hooked up to a breathing apparatus. A Chinese mythic monkey-man appears and summons a large black and white drawing of a dragon that he places over Ivens’ body. We then see the shadow of a puppet dragon being ridden by a man fly out the window, and up to moon. Cue shots from A Trip to the Moon (1902), that iconic early sci-fi film. Ivens then duplicates the set of the moon from that early film for a segment where he meets a character from a Chinese myth, and she does a dance for him. Yes, it’s all a little bizarre, and certainly not a documentary there, but it’s sweetly magical, and I really loved the reference to and reverence of A Trip to the Moon.

The second segment that I enjoyed was Ivens’ trip to see the terracotta warriors. The first part of the segment, certainly a documentary, shows Ivens attempting to enter the museum with his crew but being stopped by Chinese officials and being told he can’t film. He then shows us the days of negotiations where he argues with the officials that he has the permits and wants to film, but their restrictions are too great, and he eventually walks out. Still determined to film the warriors, he instead decides to buy street market replicas, and now I’m not sure if it’s still a documentary. A happy little scene shows Ivens on the street in his wheelchair with his many assistants gleefully purchasing as many replica warriors as they can get their hands on. They set up all the replica warriors and film them instead. This section moves fluidly from documentary to fiction to downright surrealism. How is it that Ivens can, in the same section of film, so fluidly move from documentary to surrealism? They are antitheses of one another; and yet, the mood he sets up in this film makes it possible. I don’t doubt it for a second. Truly unlike anything else.

There are certainly sections of the film that are more tedious than others – the beginning, for example – and though the movie is brief, sections of it seemed to slow way down. Having said that, pretty much every time I started to feel the film was really dragging, inevitably Ivens would then have some sort of bizarre, mythological, or fantastical moment that instantly livened the mood and quickened the pace. I really cannot overemphasize how joyous these moments are. Even a lightning quick scene of a Chinese mythological warrior shooting down nine of the ten suns in the sky, despite its inexplicable inclusion, is nonetheless cheerful.

This is a film that defies classification other than “experimental,” but this is one of the happiest experimental films I’ve seen. For that fact alone, A Tale of the Wind is extremely unique – and enjoyable.

Arbitrary Rating: 7/10

There's some real beauty in this film. It's really special, but, as you say, difficult to put in a box.

ReplyDeleteMost experimental films are such chores for me, for lack of a better word, and this one never felt that way. It's befuddling, but beautiful!

Delete