Thursday, September 27, 2012

Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters

Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters

1985

Director: Paul Schrader

Starring: Ken Ogata

Ah, Mishima. Yet another sterling example of why I love, adore, and cherish 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die. The first time I saw this movie, I had never heard of it and knew nothing about it. Half an hour in, I was a little confused, but beguiled. By the end of the film, my jaw was on the floor and my heart was in my mouth. It had shocked, stunned, and most importantly moved me. This movie is phenomenal.

Ostensibly a biopic, although more on that later, Mishima is about Japanese writer, poet, dramatist, actor, nationalist, and all around artist Yukio Mishima, brilliantly portrayed by Ken Ogata (he who broke my heart over and over again in The Ballad of Narayama). Mishima is a legendary figure in modern Japanese history, and the film opens on the day in 1970 that he and four members of his private army successfully broke into a Japanese garrison and held the general hostage. We flash back to various earlier points in Mishima’s life and various pieces of fiction he wrote, a significant portion of the film, all while returning occasionally to the day of the garrison raid. By interweaving the art with the life of the man, Schrader paints one of the best cinematic portraits of an artist I’ve ever seen.

The basic structure of the film took me awhile to understand when I first watched it. There are fundamentally three strains of the film, and Schrader differentiates between them primarily through the use of color. Mishima’s life other than the day in 1970 is shown in black and white. His dramatized pieces of fiction (three of his stories are told) are shot in staggeringly saturated hues, reminiscent of Technicolor, but actually achieved with regular film stock and terrific lighting and sets. The day in 1970 is shot in color, but a dull, grainy, muddy color, like an old television episode from 1970. The film moves back and forth between these three elements consistently throughout its four “chapters,” each of which highlights one of the three dramatized works, with the fourth chapter focusing solely on the day in 1970.

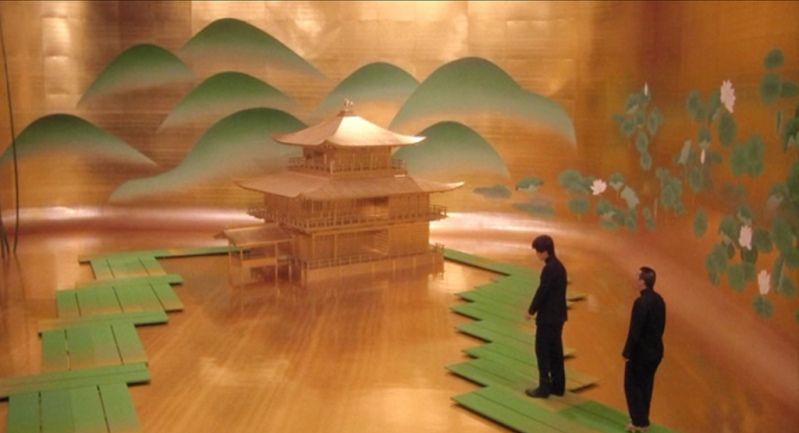

So right off the bat, the film has a fascinating structure that requires more effort than falling asleep on the couch. The intercutting between the dramatized stories and the black and white flashbacks is further done in such a way as to draw a clear parallel between Mishima’s life and the characters and events in his work. As a young child, Mishima stutters. We then immediately cut to “The Temple of the Gold Pavilion,” a story whose main character stutters (this is the part that confused me in my first viewing). This connection between life and art is Schrader’s key thesis point about Mishima. Not a wholly novel concept for a biopic of an artist, but the difference here is that Schrader questions the line between art and artist, and whether it was Mishima who created his art, or Mishima’s art that created Mishima. In each of the three dramatized pieces, we have straightforward parallels drawn between Mishima’s current stage of life and the art he created, but the art also provides unnerving insight into Mishima himself, insight we do NOT get from the simple flashbacks. Consider “The Temple of the Gold Pavilion.” On one hand, yes, both Mishima and his main character stutter. Very simple. But the story told in “Gold Pavilion” is about a young acolyte so desperately overcome and overwhelmed by the beauty of the titular pavilion and the world around him that he is alternately paralyzed by it, then angry at it. We have here an insight into how Mishima feels about the world around him, and we see a frightening flash of destructivism that is not being vented. The second story, “Kyoto’s House,” is about a stage actor/director, paralleled with when Mishima was himself an actor/director, and features a main character who takes up bodybuilding while, you guessed it, the real Mishima takes up bodybuilding. Again, though, superficial similarities aside, the story delves further into Mishima’s psyche, showing us a fictional man who, yet again, is overcome or unhappy with the beauty around him, and starts to dabble into dangerous feelings of self- or partner-induced cutting. From the first to the second story, we have an important shift from destructive feelings focused on an external object, to destructive feelings focused on causing pain to oneself. With the introduction of the third story, “Runaway Horses,” we see Mishima become more interested in an imperialistic military, and a story about young soldiers who are willing to make the ultimate sacrifice for their emperor. That feeling of self-destruction is still there, but now it is given a meaning, a grand, noble, sacrificing meaning. It’s far too easy to see how the three pieces of fiction shown in the film clearly delineate the path that Mishima walked in the final chapter of the film.

More than any other biopic I have ever seen, Mishima achieves that elusive effect of explaining not the life of the subject, but the mind of the subject. Personally, I find typical biopics rather dull. There are good ones, sure, but most seem formulaic; ironic, considering they are “based on real life.” Artistic biopics tend to be one-to-one in their structure as well, showing something happen to the artist in real life, then cut to a scene where artist creates a work of art based on previous real life event. Mishima blurs these lines. We have few scenes of Mishima actually creating art. There is narration where Mishima talks about his desperate need to write, but the sequences of his real life that we see are more about his philosophy than about how one act lead him to create a certain piece of art. Moreover, in terms of a biography, there are certain events in his life that are completely glossed over. His marriage and children, for one, is completely absent from the film save from a mention in the very opening scene. He picks up a phone and asks about his wife and kids. And we never see them. Schrader seems to be saying that we don’t NEED to see Mishima’s traditional life touchstones in order to understand his work, and that’s exactly what makes this a fascinating biography to me. It is not through reliving his life that I will understand Mishima, but through a blend of certain memories with his art itself that I will understand him.

Because really, this movie lets you understand Mishima. He was a complex, thoroughly three-dimensional person, and this is a movie that presents a complex and well-rounded presentation of a challenging human being. The first time I saw this film, I had this dawning comprehension of really understanding the subject. I understood how Mishima felt about beauty. I felt his frustration and sorrow about his art. I began to comprehend how he increasingly saw “action” as a perfect statement of art. And, as the film draws to its conclusion, I understood. I understood the final chapter, as horrible as it is. Far too many biopics simply show me an artist. Mishima takes me deep inside his brain, better than any other biopic ever has. There are not enough superlatives in the world for this achievement, and I am forever and permanently moved by the experience.

To give credit where credit is due, the previous point that I (not so concisely) made is attributed to Ogata’s performance, the screenwriters’ script, and Schrader’s direction for having the ability to pull off such unconventional storytelling techniques. The film would be more than amazing if we just left it at that. But no, Schrader now heaps on some of the finest production values I have ever had the joy to witness. Mishima is a visual treat. The three threads of the film (flashbacks, dramatizations, and 1970) all have distinct visual styles. The black and white of the flashbacks is a rich and lush black and white, reminiscent of the black and white style of the forties. There is a distinction in black and white films; some are sharp and crisp, some are gauzy. Schrader purposely references Japanese directors of the fifties in the black and white segments, with some great interior shots reminiscent of Ozu and Mizoguchi. Then, my goodness, we are struck over the head with the intensely saturated color of the dramatizations. Achieved purely through sets and lighting, these are the most highly-stylized segments of the film. Schrader eschews realism for these segments, further playing up the fact that they represent Mishima’s art. The sets (designed by Eiko Ishioka) might just be some of my favorite setwork in all of cinema. Yes, that’s a hyperbolic statement, but dammit, that’s how I feel about this movie. You have not seen sets like this until you’ve seen this film. Completely artificial yet deliciously rich, they are also highly confined. We have several overhead shots looking down on the entirety of the set in question. Surrounded by darkness, we see four walls creating the cubicle of the set, but then the camera descends into the cubicle and we are in that world completely. The color palette alters with each tale, and it is “The Temple of the Gold Pavilion” that is most beautiful (fitting, considering the tale is about beauty), with “Runaway Horses” being the most striking (fitting, considering the tale is the most aggressive and idealistic). Cinematically speaking, the dramatizations are the most vibrant part of the film.

Which takes me to the production of the third strand of the film, the day in 1970. Considering that the film has made the very clear point of stating that Mishima’s life is in black and white and his fiction pieces are in bright color, we suddenly have a day in his life that is shot in color. It’s a muted, muddy, flat color, full of olives and browns and grays, but it’s color nonetheless. Ah, such a beautiful little point. The day in 1970 is the culmination of Mishima’s belief that art and action should meld into one and the same; that day in 1970 IS his art, but it is also his life. It is, perhaps, his ultimate act of performance art. Thus, we have a blending of the black and white AND the supersaturated color. Art meets action meets life. Genius.

Philip Glass’ score is a fantastic example of a score that doesn’t obviously fit the action on the screen, but because, or in spite, of this, manages to be nonetheless perfect. Granted, most of the score is simply repeated arpeggios played by various strings or synthesizers, but it works. It imbues a sense of tension and excitement. Glass’ work stands out, and is easily identifiable as ‘Philip Glass,’ but I love that his stuff is a little different. Frankly, I get tired of predictable symphonic scores that wind up sounding more like lounge music. Glass does not fit this description, and I can see how he went from Koyaanisqatsi to this. A terrific score.

It’s so difficult to try to sum this film up. It’s so many things: revealing portrait of an artist, tremendously stylized story, rule-breaking narrative structure, gorgeous score, great writing. It’s also a cross-cultural production. This is an American film, with American producers (which include George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola) and an American director, a film that got Japanese funding for its Japanese cast to shoot in Japan with a Japanese screenwriter, telling a story about a Japanese persona. Having said all of that, Mishima is banned in Japan and has never been shown there, but not for the lurid reason you would expect. Apparently, Mishima the man is still so respected and revered in Japan that the authorities fear this film would stir a certain imperialistic right-wing minority into dangerous action. If any film had the capacity to do that, Mishima does. This is a staggering piece of cinema.

Arbitrary Rating: 10/10. Did I gush enough for you to figure that one out in advance? I mean, this film is so good, and moved me so much, that this manages to rank as a "Best of the Best" for me. WOW.

I'll also add that it was damn near impossible to pick images from this film for this post. There are far too many gorgeous shots.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

This really is a spectacular film. I went into this cold and came out of it feeling transformed, amazed that film could do something to me that I didn't expect. I called it "a magnificent achievement," and looking back, I probably undersold it.

ReplyDeleteSo glad you feel the same way too. This movie is so incredible. I love that feeling of "going in cold," as you say, and coming out on the other side profoundly moved. Frankly, that's the main reason why I watch movies. I watch movies to find the films that make me feel the way this film made me feel. I don't think there's a higher compliment than that.

Deleteadidas ultra boost

ReplyDeleteyeezy boost 350 v2

retro jordans

balenciaga

adidas ultra

yeezy boost 350 v2

cheap jordans

kyrie shoes

coach handbags

kyrie 5