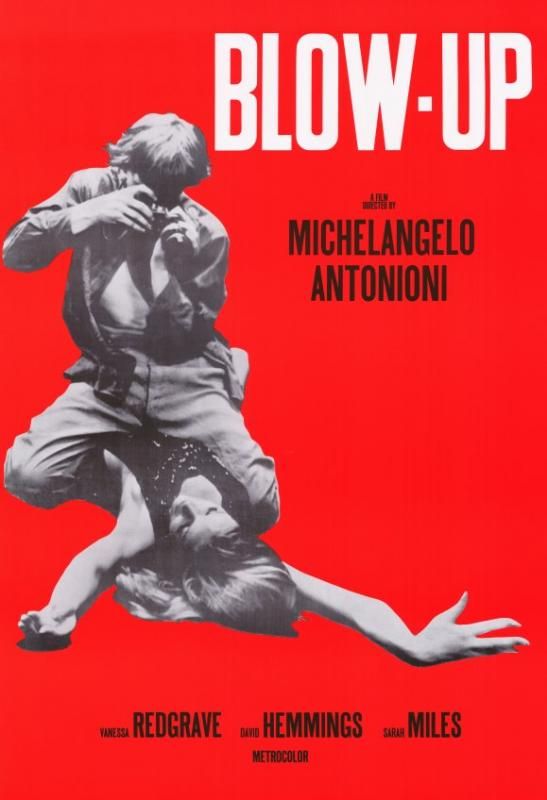

Blow-Up

1966

Director: Michelangelo Antonioni

Starring: David Hemmings, Vanessa

Redgrave

Antonioni

is a director that I struggle with, and I don’t feel ashamed to admit it. His work is hardly what anyone would call

“easy.” He likes to make films about

alienation, which is not an easy or entertaining topic. Of all the Antonioni films I’ve seen, Blow-Up

is the most accessible, but even that’s not saying much. This is my second pass at Blow-Up,

and while I feel as though I “get it” a bit more than the first time, it is not

what I would consider to be entertaining.

Set

in a swinging London mod scene that is everything Austin Powers was skewering,

a trendy photographer (Hemmings) is bored.

Bored bored bored. So one day, to

escape the boredom of shooting more vapid fashion shots, he takes his camera to

a park and starts shooting landscapes.

He sees a young woman (Redgrave) and an older man who seem to be

canoodling, and keeps shooting. The

young woman gets distraught when she sees him and demands the film. He refuses, she tracks him back to his studio

and tries to seduce him to win back the film.

He still refuses, then starts examining this precious film. The more he looks at it, the more he thinks

he sees… something. But what, exactly,

and what does it mean?

I

think the reason I was a bit disappointed when I first watched Blow-Up,

and why I was less so this time, was that initially, I thought it was about the

mystery of what was on the photos. Let

me be as explicit as possible here: if you watch Blow-Up expecting a great

mystery, don’t. Just don’t. That’s not Blow-Up. The mystery, such as it is, occupies

approximately half the film, if that.

The other half of the film is about the photographer’s lifestyle, and

that, to me, is what this movie is REALLY about. By “lifestyle,” I don’t mean the ridiculous

swinging mod London, sex with groupies, or rock concerts. No, I mean the photographer’s

personality. His alienation. His existential coma.

The

first half hour of the film sets up the photographer’s boredom. He comes alive most when he is taking photos,

but not even taking photos is a guarantee that he will enjoy himself. Look at how awful he is to the models during

the early fashion shoot, barking orders at them and treating them with cold

cruelty. He doesn’t seem like he’s

having any kind of fun. We can feel him

rolling his eyes as some groupies try to get his attention, and even a

conversation with his neighbors, who he appears to like, does little for

him. In the park, though, he gets

excited. We see a sort of animal spirit

begin to appear. This same excitement,

after ebbing, comes back when he starts examining the film. Antonioni seems to be saying that our

photographer (IMDB says his name is “Thomas,” but he is never properly given a

name in the film) has a life that is empty and hollow, but when he is most

embroiled in his craft – in taking pictures of things he likes, of developing

interesting film, of blowing up certain shots – then he is most alive. Then he is not a dead soul. The possibility of a mystery engages him in a

way that vapid sex doesn’t, but the film closes in the last half hour with his

spiritual awakening ebbing away for good.

The mystery starts to fade, the proof begins to disappear, and slowly,

our photographer is drawn – perhaps against his will, perhaps not – into his

superficial life of the beginning of the movie. The final shot of the film, in which our

character literally disappears (that is NOT a spoiler in any way), is a huge

statement about this superficiality. That is the journey of the film: watching a

man find something that interests and engages him, then watching it run out of his

fingers like cupped water.

Antonioni

is known for his color work, and there is very nice color work in Blow-Up. There are bright reds and blues on the

buildings of London, insanely bright whites and ebony blacks in the

photographer’s studio, but my favorite is the green of the park. The park is perhaps the most significant set

in the film as it sparks, and then concludes, our photographer’s interest. This is a brilliant green, a terrific emerald

green. The grass is green, the trees are

green, the fence is green. And the park

is surprisingly vacant – the green is not interrupted. The sky, interestingly, is not blue, but gray

and overcast. I think that’s significant. Antonioni was highly specific about his colors,

to the point where he actually shot the park sequence twice in Blow-Up

because he didn’t like the green of the grass on the first go, so he had it

spray-painted just the right shade and then shot it again. If he had wanted the sky to be blue, he’d have

waited for a nicer day. But no, he must

have wanted the sky to be gray. In a

way, this seems to make the other colors pop.

I love the contrast of the gray and the green together. Gray, overcast days are my favorite type of

weather, and I think a feel a bit of a connection to seeing this onscreen.

This

is a very silent film. I wouldn’t be

surprised if all the dialogue from the film could fit on ten pages worth of

script. There are long, loooooooooooong

stretches where no one says anything.

And Antonioni doesn’t help cut the silence by providing background

music, oh no. There is almost no

soundtrack to this film. No one talks,

and there is no music. During the scenes

where the photographer starts to delve into the mystery of the film, this silence

is effective in building tension and excitement. But for nearly every other part of the film,

though, this silence feels tedious. Yes,

it underlines our main character’s dreariness, but it itself is also dreary.

Which

leads nicely into my final feelings about Blow-Up. I understand now, better than previously,

that Blow-Up

is about ennui. But does that make it

something I like? I don’t think so. Frankly, watching a movie about someone who’s

bored is, well, boring (Jeanne Dielman, anyone?). A film about someone suffering from swinger

angst, bored to death of his tedious glittering lifestyle? I have very little sympathy for our main

character. He disappoints me by sick and

tired of his superficiality, but then is completely unable to extricate himself

from it. I *was* more engaged in this

second go-around, again because I knew not to expect too much from the mystery

and to look more at the photographer’s emotional arc, but this film does not

earn a rave from me. I get Antonioni’s

message. But, y’know, that’s about

it.

Arbitrary

Rating: 7.5/10. It was good for me to

watch this a second time. I found more

there. This score is more about

appreciation than entertainment, though.

I don't understand why anyone should be bored (unless you're watching a film about boredom). Why doesn't he find a hobby, or volunteer, instead of being self-absorbed and sulking? I will never understand people.

ReplyDeleteHee hee hee! Indeed, Lindsey, I am inclined to agree. I am now picturing our photographer from Blow-Up heading down to the Salvation Army or food shelter to volunteer, and that thought's making me laugh.

Delete