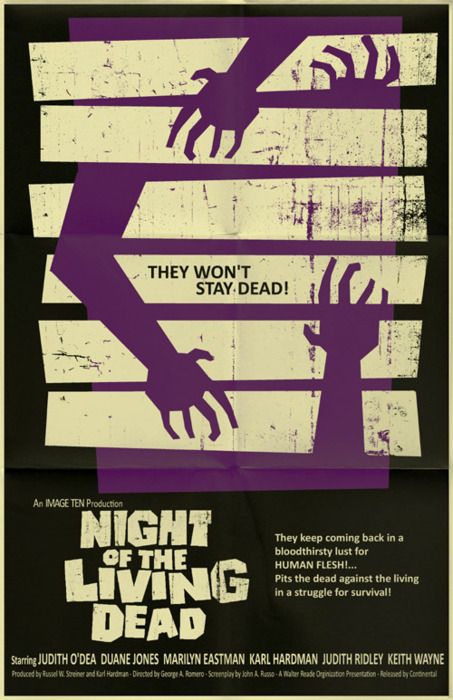

Night

of the Living Dead

1968

Director: George A. Romero

Starring: Duane Jones, Judith O’Dea,

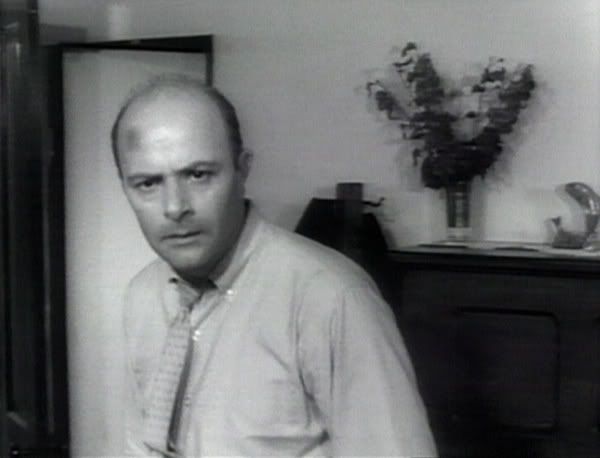

Karl Hardman

So

I’ve been incommunicado for the past few days.

Why? Because my friend Angie came

to visit me. Who cares, and why are you

telling us, you might think. First of

all, I have been online friends with Angie since 2006 but this was the first

time we’ve ever met in “real life,” (AND IT WAS AWESOME AND AMAZING AND FULL OF

FANGIRL FLAILING) so that was significant, but Angie also came to visit for a second

specific reason. Angie was into zombies

before zombies were de rigueur. Angie

wrote her undergraduate thesis on socio-political constructs in zombie

films. Angie is THE expert in all things

zombie. And the Dryden screen Night

of the Living Dead this past weekend.

Thank

you, Dryden, for bringing my friend to me and allowing us to meet and talk about

classic zombie films in person.

The

story of Night of the Living Dead is straightforward. A young woman, Barbra (O’Dea), is visiting a

cemetery to put flowers on her father’s grave when she sees a slowly moving

body coming towards them. The thing

kills her brother and Barbra flees for the safety of a nearby farmhouse, where

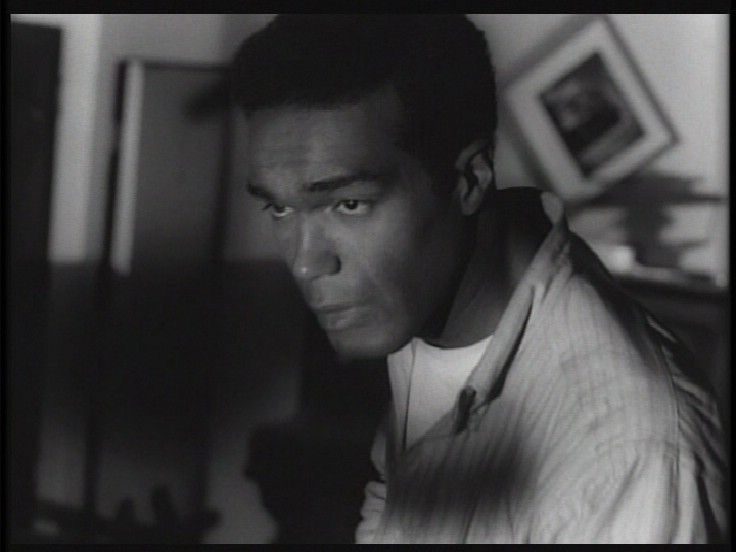

she is quickly joined by Ben (Jones).

Ben barricades the house and has phenomenal survival skills, especially

compared to catatonic Barbra. They are

eventually joined by a handful of other survivors and tensions rise among the

group when Cooper (Hardman) clashes continually with Ben. Details of the reason for what we now call a

zombie attack slowly leak to the people in the house. Can the group survive the night?

So

much of what makes Night successful comes down to its resolution, so I will say

right now that if you are somehow, amazingly unspoiled on this horror film

classic, stop reading then go watch the movie.

It

is very difficult to overstate just how significant this film is in horror

movie canon. I am not a horror movie

buff, I seldom choose to watch horror movies (because I’m a wimp at heart), but

I’ve seen many of the “significant” horror films thanks to 1001 Movies

and I feel like I have a decent grasp on the evolution of the genre. Just as the French New Wave revolutionized

standard Hollywood filmmaking in the late sixties, the effect of Night

of the Living Dead was to take so many “standard” classic Hollywood

horror tropes and rip them up, spin them around, and usher in a new philosophy

of fright. When you tack on the

staggering fact that Romero also manages to make this into an insidious

socio-political commentary, you’ve got something that is nothing short of

game-changing.

Consider

first how Night compares, in terms of sheer concept, to the “monster

flicks” of the thirties, forties, and even fifties. Instead of posh sets and elegantly articulate

actors, realism (due to budget constraints) reigns supreme. This is not a monster pic in the world of

some gothic Victorian village, this is real people in the real world facing a

threat. Although I very much enjoy Lon

Chaney Jr.’s The Wolf Man in particular, Night refuses to create that

kind of posh, elegant horror movie. What’s

more, consider the threat itself. Angie

is always quick to point out that zombies have a significant distinction from

other classic horror monsters in that zombies are ourselves. Vampires, Frankenstein, werewolves, these are

all horror monsters that have some element of separation from humans. But zombies, ah, they are different. As Night eventually says, anyone who

dies during this zombie attack from any cause will then turn into a zombie

themselves. Even setting itself apart

from the monster films of the fifties like The Blob and Them!, with whom Night

shares the concept of some sort of foreign attack closing in on a group of

characters, the central threat in Night cuts a little too close to

home. Zombies are not killer ants from

outer space, they are us. They are humanity

itself. Current settings and a monster

threat that manages to be both supernatural and too close for comfort at the

same time rewrote many of the rules for classic horror.

To

me, this is interesting from a historical aspect, but what makes Night

even more significant is its tone. Yes,

there had been monster invasion movies popular in the fifties, but none of them

had the streak of utter, unrelenting nihilism running through them that Night

has. Our group of survivors in the

farmhouse numbers seven total (Ben, Barbra, Cooper, Cooper’s wife, Cooper’s

daughter, and young couple Tom and Judy), and not a single damn one makes it

out alive. What… what is going on

here? What did Romero do? That’s not right. We’re supposed to have at least one member of

our band of gallant fighters live through the night. Sure, we might not expect everyone to survive,

but we certainly don’t expect everyone to die.

Even by today’s standards, killing off every damn one of our protagonists

is a gutsy move. It’s a game changer. “You can’t do that,” someone must have said

to Romero. “Watch me,” he undoubtedly

replied.

It

is this unrepentant nihilism that completely changed my perception of Night the

first time I watched it. I remember

watching it through, unspoiled, with a sense of “Well, this is nice. I can somewhat see why this movie is a big

deal. It’s fine.” The film reached its climax and Ben

survived. “Great, cool, Ben survives,

alright, movie over, large death toll but we have the survivor.” Nope.

When Ben died, it was one of the few moments in film that actually made

me gasp and clap my hands to my mouth. I

couldn’t believe that had just happened, and in that one brief, cruel moment, Night

of the Living Dead went from “nice” to “yeah, okay, WOW, I *completely*

understand why this movie is a big deal.

Holy crap.”

And

speaking of Ben, how can I not. Famous

for casting a black man in a movie filled with white characters and without the

intention of making him black (Duane Jones simply gave the best audition, Romero

said) is nothing short of groundbreaking.

Making that character the most resourceful and level-headed person in

the film, even better. And then unceremoniously

shooting him in between the eyes, killing the character not by zombie attack, which

Ben is smart enough to survive, but by the rescuers who assassinate anything

that moves, is nothing short of heart-wrenching. I cannot imagine living in an America in 1968

that had just lived through the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. mere

months prior to having Night unleashed on them. Racial tensions were notoriously high, and

along comes a horror film, of all things, that zeroes in on them and splays

them across the screen for all to see. As

my friend Angie knows with far more authority than I, Romero is a director

dedicated to providing positive portrayals of both women and people of color in

his films; he just happens to make his profound social statements through the

medium of zombie films instead of academic articles. The discontent of the American populace is

somehow distilled down and incorporated, making the horror film not just

mindless entertainment but a gauge of public attitudes.

Although

filmed on a scant budget and looking like it (with some gawdawful performances,

as Angie was constantly sniggering at Tom and Judy), Night of the Living Dead

retains its power over time through its innovative storytelling and its

fearlessness to confront social issues. Although

it might perhaps seem formulaic for a zombie film by today’s standards, you

must remember that this is the film that WROTE that formula. It’s not formulaic if you invent it yourself. This is a film that deserves its place in

history.

Arbitrary

Rating: 8/10

PS

– ILU, ANGIE!!!!!!!!

Do me a favor--this is a hobby horse I've been riding for awhile. Angie, as a fan of all things zombie, can weigh in, too.

ReplyDeleteAs groundbreaking as Romero's film is, it's not the first zombie film. I contend that Hitchcock invented the genre in The Birds. The last half hour of that film--boarding up the house, creatures attacking from outside and trying to get inside, creatures attacking for some unknown reason--Romero took that half hour and expanded it into this film.

Don't get me wrong--he's genius for doing it. But I still say Hitchcock invented the formula, or at least made the formula respectable.

Oh, Steve. Why do you have to go making reasoned, logical associations that seem so obvious once you say them.

DeleteI think I'd take issue with calling The Birds "zombie," what with the lack of the undead and the rather fascinating idea that the enemy in zombie films is humanity itself, your dead neighbors and friends, etc. But I definitely think your point re: the boarded up house is significant. I guess I would credit Hitch with, as you say, legitimizing the "standoff" idea in horror films, no small feat indeed, and then Romero co-opted that concept, making the enemy the zombie rather than the birds, and all that goes along with what is now the traditional the idea of the walking dead.

While I acknowledge this movie's place in the horror genre, and in films in general, it didn't do much of anything for me when I watched it. I did not know what was going to happen at the end, but for whatever reason it did not surprise me. I think just the overall tone of the film made me assume that no one was getting out alive. The part of the movie I liked the most was the interplay within the house.

ReplyDeleteWith all respect to Steve, I don't feel The Birds is a zombie movie precisely because there are no zombies. Yes, people are trapped in a house and under siege, but that kind of scene had happened prior to The Birds in any number of westerns. Of course, some argue that Night of the Living Dead isn't a zombie movie either since the word "zombie" is never uttered once in the entire film.

Fair enough.

DeleteBut if one make the argument that if the use of the word "zombies" is required to make something a zombie movie, then you're removing nearly half the genre. I know "The Walking Dead" calls them walkers, not zombies. Because people in zombie movies don't know they're in zombie movies, so why would they use the word "zombie?"