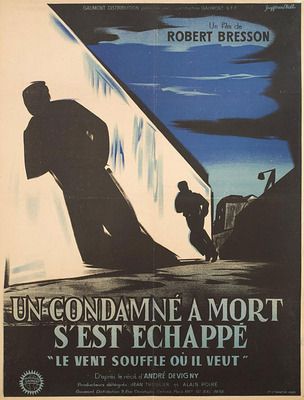

A Man Escaped

1956

Director: Robert Bresson

Starring: Francois Leterrier

A Man Escaped is a rare little bird of a film. It’s easily one of the most thrilling prison break films I’ve ever seen, but it doesn’t fit the mold of a prison break film. It’s easily one of the most suspenseful films I’ve ever seen, but it lacks so many of the basic components of suspense films. The director, Bresson, manages to craft an enormous film by keeping things incredibly small.

The film opens on a shot of Fontaine’s (Leterrier) hands. He is in a car, being driven to prison. His hands slowly move toward the door handle. He watches the traffic like a hawk, looking for an opportunity. There is a cart up ahead – he sees his chance – the door opens, he makes a break for it… and is then immediately escorted back to the car. Once he gets to his prison, he is punished, but immediately starts planning his escape. The title is a little (well, a lot) of a giveaway, but tells you very clearly what the story is about. This is clearly about Fontaine’s escape.

So much with the hands!

So much with the hands!Watching a Bresson film is like watching a master class on minimalism. He is king at showing the least and yet getting the most out of it. Take, for example, his lead actor, Leterrier. Leterrier was not a professional actor; he was a graduate student in philosophy studying at the Sorbonne when Bresson discovered him. His eyes, his face – Bresson was intrigued, and knew that he could carry the film despite his inexperience. He was right. Bresson doesn’t really want his actors to act in the traditional sense. Rather, he wants them to simply be a part of the scene and the story, rather than furthering the story themselves. A professional actor would want to act, but Leterrier simply “is.” He inhabits his space. No gasping, no melodramatic scenes of yelling or fits or anger, no triumphal exclamations, and yet the film makes you feel all of these things. The difference is you don’t SEE them in the film, but you FEEL them.

Then consider the shots in the film. Most prison break films are done on a grand scale, telling a grand story of the righteous hero versus the evil guards, necessitating large sweeping shots. Bresson says no. Once Fontaine arrives in his cell, the shots become necessarily claustrophobic. We rarely see all of Fontaine’s body, instead focusing on a close shot of his face, or hands, or his torso. The only time the camera seems to allow us to see all of Fontaine is during the once-a-day walk around the prison yard when he empties his slop pail, and even then, there are no overhead large shots; it simply pulls back enough to show Fontaine walking. The camera reinforces the cramped living quarters, which in turn emphasizes just how small the world has become. Even during the eponymous escape scene, the camera is focused on one small thing at a time rather than the grand triumphant escape.

The sound in this film is phenomenal. Bresson eschews a traditional soundtrack, opting instead for mostly silence. After all, prison is silent. There is no music when Fontaine is in his cell. Why on earth would there be? It’s a prison cell. When Fontaine is taken out in his daily walk around the yard, that time is often punctuated by the briefest moments of classical music (Mozart), as if the physical act of being outside itself is worthy of a burst of beautiful song. Once returned inside, however, the music stops and the focus becomes on the sounds of the prison. The footfalls of the guard. The amount of noise Fontaine makes scraping at his door. The unscrewing of his mattress. The breaking of the glass pane in the lantern. Every noise seems magnified, almost surreal. In the final escape, when Fontaine slowly lowers his foot onto the gravel path after descending a wall, the entire theater drew its collective breath at the volume of the noise. Surely the noise would alert a guard! Again, Bresson focuses the viewer to the very small things, but by consistently doing this, by consistently emphasizing the smallness of the world of the film, the smallest things become enormously important.

I love this film so much. I love this film because it makes me hold my breath for nearly 99 minutes, but it does it in such an unconventional way. We don’t know why Fontaine is escaping; he doesn’t harp on about needing to get back to his wife and kids. It doesn’t matter why he escapes; it is far more important THAT he escapes. He must escape. He simply has to. He cannot be contained. I love that even, despite the lack of motivation, Fontaine’s spirit is incredibly clear to the audience. I love how quiet and yet how powerful it is.

The more and more I watch film, the more I realize that, for the most part, I prefer small films to large films. Bloated epics are increasingly my least favorite genre. Gone With the Wind is known as “Four Hours Siobhan Will Never Get Back.” Bresson’s films, and A Man Escaped in particular, are the complete antithesis to such giant messes. He sees the joy in the little things, the importance of telling a story on a small scale, and knows exactly how to elicit an emotional response from the least amount of material.

An absolutely wonderful, brilliant, and incredibly tense 10/10.

No comments:

Post a Comment