Tuesday, September 18, 2012

The Lady From Shanghai

The Lady from Shanghai

Director: Orson Welles

Starring: Orson Welles, Rita Hayworth, Everett Sloane

1947

Orson Welles is such an enfant terrible. His films are brassy and bold, ballsy and gutsy, flying in the face of tradition. With The Lady from Shanghai, Welles, married to Rita Hayworth at the time, managed to piss off most of Hollywood by taking Hayworth’s gorgeous long red locks, cutting them all off, and dying them blonde. This move, heretical in terms of Hollywood’s star system, sets the tone for the rest of the film. Welles set out to make a film noir, and ended up making a film noir on crack.

Welles plays Michael O’Hara, a sailor who becomes infatuated with beautiful Elsa Bannister (the gorgeous Hayworth), only to find out she’s married to a leech of a cripple of a criminal lawyer (Sloane). Bannister the lawyer employs O’Hara on his yacht, practically inviting danger, and when things turn murderous, everyone’s in trouble.

The film opens with a carriage ride in Central Park, a generic image rife with wholesome good cheer. This scene, so seemingly charming and quaint, underlines how nasty and vicious the movie becomes. O’Hara narrates the film in the tradition of films noir, and he laughs at himself over the action as he beats up some two-bit thugs who are attempting to rob Elsa Bannister. “Almost makes me look the hero,” he says laughingly. In typical films noir, the hero, such as he is, is done in by his fatal flaw. He is fundamentally good, but trouble seems to find him. O’Hara is different; he is hardly fundamentally good. On the contrary, he seems fundamentally corrupt, fundamentally greedy, but yes, trouble still seems to find him. Furthermore, everyone else around him seems built of the same smelly, shady clay. Mr. Bannister knows exactly who and what O’Hara is, and is apparently determined to bend him to his evil will. Everett Sloane, one of Welles’ stock actors from his Mercury Players, is deliciously cunning in his portrayal. His bug eyes, his limp, and his condescending calls of “Lover!” as he taunts his wife are hypnotic on screen. Elsa, despite her blonde halo, is hardly an angel. Hayworth, still underappreciated in terms of her acting skills to this day (I also might have a wee bit of a girl crush on Hayworth), is wonderfully cold and calculating as she alternately seduces and destroys Michael. She is one of the best femme fatales in the noir catalogue, playing off Michael’s misconceptions and vulnerabilities, and Hayworth easily handles the role, making her inexplicably evil. Welles and Hayworth were having marital difficulties at the time, and I don’t wonder if it didn’t make its way onto the screen, with all the hate that is slung back and forth throughout the story.

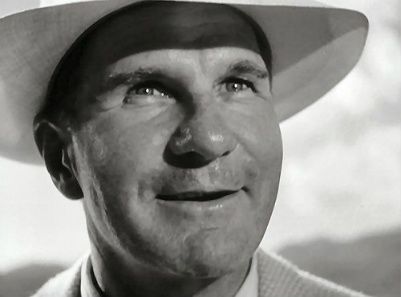

The leads are all brilliant, but it is Glenn Anders in a supporting turn as the greasy, sweaty George Grisby who manages to steal the show from his stellar counterparts. Welles directs Grisby to perfection, giving us uncomfortable close-ups, lingering on his evil laugh, his lecherous gaze, and his fascination with murder. When he first introduces himself to Michael, he keeps on bringing up the fact that Michael has killed a man, he wants to know how it felt, how he did it, and what became of it. He’s almost disappointed when Michael tells him he killed a man during wartime. “Oh, it’s not really murder then, I suppose.” Grisby is so dirty, so smelly, so sweaty, such an underhanded heel, and he fits in absolutely perfectly in the grisly, dank, shadowy world of noir.

Welles’ direction is, as ever, thrilling. His close-ups, his angles, his shadows are all deliciously perfect in the world of noir. His drunks are out of focus and wobbling in the shot, his predators are sharp and keenly focused, and his beauty shots of Hayworth are coldly beautiful, as befits a femme fatale. An aquarium sequence is absolutely beautiful. Hayworth and Welles are photographed in profile with the dancing waters behind them. We don’t see their faces, they are completely in shadow, and the only light comes from the fish tanks behind them. They speak false words of love to one another, all the while the light flickering behind them. Gorgeous. Similarly wonderful but less-referenced is the courthouse sequence. Michael, realizing he has been caught in the tangled web that the Bannisters have woven, is standing trial. The shadows of the window blinds lie heavy along the walls, imprisoning Michael before he has ever set foot in the jail. The long shadows, the canted angles make for absolutely breathtaking film shots.

Without a doubt, his crowning achievement in this film is the unrivaled Funhouse Sequence in the final ten minutes. Welles pulls out all the stops in this career-defining sequence; well, it would be career-defining for anyone else. For Welles, when you have Citizen Kane under your belt, the funhouse sequence can become an afterthought. The mirrors, the slide, and the resulting brawl are dizzyingly intoxicating. Michael is literally drugged when he enters the funhouse, which makes the bizarre setting that much more effective. The shadows, the superimposed film shots, the reflections, are just exhilarating. The pale white slide, the rotating floor, the pitch black background; it almost belongs in a Dr. Seuss story, which makes it all that more heady that it shows up in a film noir. I really cannot overstate how exciting this sequence is. It’s almost too much, as befits Welles’ style. Overdosing on style, that’s Welles. Broken glass, broken mirrors, long angles, multiple reflections, gunshots aimed squarely at the camera – exhilarating. It is scenes like these that show the true beauty of black and white. Color film more than has its place in cinema, but it cannot match black and white in terms of the effect of shadows and light.

The definitive speech of the film is when Welles talks of a shark feeding frenzy he once witnessed, describing slowly and almost wistfully how the sharks started eating themselves. It is more than abundantly clear that he is talking about the rest of the characters, not only in that scene, but the rest of the film, himself included. Everyone is so evil, so calculated, so underhanded, it’s deliciously seedy.

As I’ve said before, noir grows in your blood. When you come to love noir, you’ll appreciate a film like The Lady from Shanghai all the more. It’s noir on speed, noir on crack, so hyper-realized that it makes all the other classic noirs pale in comparison. It’s SO evil, SO shadowy, SO gritty, it’s almost understandable why it pissed off the head honchos of Hollywood. Welles never liked to play by the rules; he preferred to toss the rulebook out the window. Welles does noir well, but it’s his way, with everything to the extreme. No other way would work for him. It’s what makes his films his.

Arbitrary Rating: 10/10. This is my kind of noir, man. Completely nutso over the top. I way love this movie, as you can tell by the fact that I couldn't help myself and added too many pictures for it.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

It's a second-stringer for me. It'll never be as great as a bunch of other noirs that do more right in my opinion. I liked it, but I didn't love it.

ReplyDeleteI can get that. I think I was genetically predisposed to being a bit gaga over this one. I LOVE Rita Hayworth, I LOVE Orson Welles... put it all together, and whoa. I was lucky enough to see this on a big screen once. It was AWESOME.

DeleteFinally someone to share my enthusiasm of this film with. It is truly awesome. The only minus is Welles himself as Michael. He just did not fit that role. Otherwise everything else is just delicious.

ReplyDeleteauthentic jordans

ReplyDeletehttp://www.raybanglasses.in.net

http://www.cheapauthenticjordans.us.com

longchamp uk

http://www.tiffanyandcojewellery.us.com

cheap mlb jerseys

adidas neo shoes

longchamp bags

http://www.kobebasketballshoes.us.com

jordans for cheap

cheap jordans

ReplyDeletenike off white

supreme clothing

goyard

moncler jacket

kobe sneakers

adidas superstar

adidas tubular shadow

supreme clothing

nike air max 97