Sunday, September 23, 2012

Yi Yi

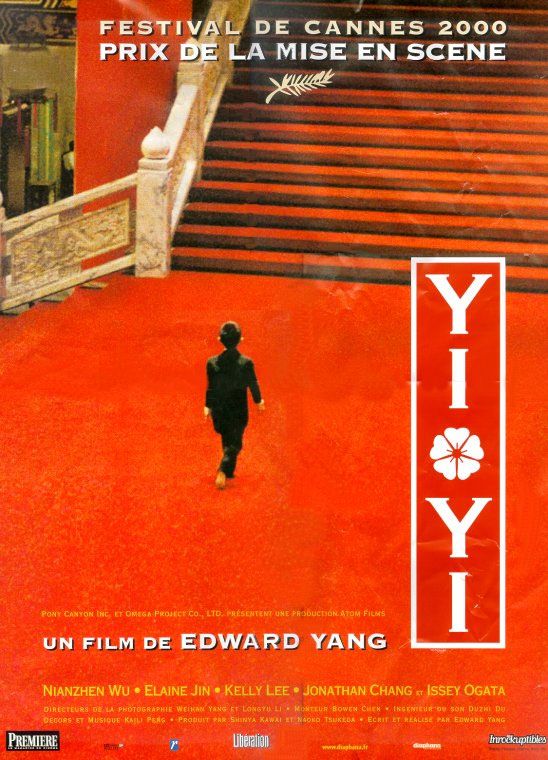

Yi Yi (A One and a Two…)

2000

Director: Edward Yang

Starring: Nien-Jen Wu, Kelly Lee, Jonathan Chang

Yi Yi focuses on the life of a Taiwanese family living in Taipei in 1999. The father NJ (Wu) has two children, a teenage daughter Ting-Ting (Lee) and a young son Yang-Yang (Chang). Around them swirls the extended family and neighborhood: a broke and bumbling brother-in-law and his young pregnant wife, the grandmother who starts the film by falling into a coma, and the apartment neighbors who argue loudly and often. The movie takes place over the course of about one year as we watch this family go through the typical trials and tribulations of life.

In a film as rambling as this, filled with many small moments but no overall narrative direction, it practically invites the viewer to interpolate their own meaning. For me, throughout nearly all the vignettes, I got the feeling of the sorrow of banality. Is life really meant to be simply a series of repeated days, one exactly like the other? The mother’s speech when she is in the throes of an existential crisis nicely sums up this particular point. There is so much of the mundane in this film; the father’s work seems utterly boring and life-draining, as does the mother’s. The wedding that opens the film seems less a celebration and more a strange party at which drunkards, fools, and bullies waste their time. I don’t see Yang as delineating the joy of the little things, but more the pathos of them.

Having said all of that, I also think that Yang offers us the solutions to this sad existentialism. One is a fairly standard cinematic solution: love. When the father starts to reconnect with his old high school girlfriend, we can see his soul begin to awaken again. When the daughter has her first experience with love, there is excitement and the sense of breaking from the soul-crushing day-to-day norms. Even the young son feels the stirring of that wonder. On the other hand, Yang also warns us of the dangers of love, played out in several storylines. The next door neighbor cannot seem to keep a man longer than a few weeks, and her teenage daughter appears to be following in her mother’s footsteps. The brother-in-law married a woman he shouldn’t have, while his real soulmate is forced to watch from the sidelines. Love is a wonderful thing, Yang says, but it’s also rather terrible.

The other solution Yang gives us is to this problem is one not as often explored in films: music. Many characters engage in music throughout the movie. The next door neighbor’s daughter is a brilliant cellist. The daughter plays the piano. The father listens to his Discman. Many characters go through CDs to pick out a tune to listen to. Even the English title of the film has musical meaning. Music is an escape for the soul, a way of expressing the most ineffable ideas. As a musician, I completely understand this idea. Something happens when I listen to Beethoven: I am transported. But Yang also throws in some pessimism about music for good measure. Society does not always understand the value of such a thing. As the father says, if you cannot put a price on it, what good is it to a business man? The next door neighbor tells the daughter that it’s better to be good at books than good at music. Yang disagrees with this, but he also knows that society as a whole is more apt to side with this particular belief.

So much of this film is shot from far away. There are so few close-ups. I really got the sense of being an outside observer of these people and their lives. We can hear them just fine; Yang lets us into their conversations, but purposely keeps us from seeing their faces time and time again, as if he doesn’t want us to see the emotion in their eyes. As if he wants to keep something from us. Body language, therefore, takes on huge meaning in this film, as it’s often the only clue we get as to the context of a speech. Similarly, we see so many scenes unfold not actually before us, but through reflections. Reflections from glass windows or doors, or shiny elevator surfaces. In some scenes, we see a character approach, only to realize at the last minute that we were actually seeing their reflection. It’s as if we can only see a shadow of these people, a glimpse, and not their whole selves, a thought echoed by the young son’s speech about only ever knowing half of the truth.

The setting of the film makes the profound philosophy behind it accessible. It takes place in 1999 Taiwan, and boy, is it ever stuck in 1999. There are Discmans and CDs and old cell phones and old fashions. It seems fitting, though, that it is tied to a particular time. And the place is most definitely Taiwan, an amalgamation of many cultures all coming together in a modern way. The father and son eat lunch at McDonald’s, the daughter goes to New York Bagels with a friend, there are Dove bath products next to the tub, and a large Batman and Robin poster is tacked onto the son’s wall. These charming touches are colorful and a little humorous, and provide a heaping dose of levity to the story.

Ultimately, Yi Yi is very much in the tradition of “snapshot of daily life” films. We are granted entry into this modern day Taiwanese family, not over the course of generations, but a single year or so. Things happen, hopes and dreams are born and crushed. Throughout all of it, Yang is inviting us to take what we will from the rambling little story. Personally, I take quite a bit.

Arbitrary Rating: 8/10.

Labels:

1001 movies,

2000,

2000s,

8 out of 10,

edward yang,

foreign,

taiwanese,

yi yi

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

adidas nmd

ReplyDeleteadidas nmd

michael kors handbags

hermes belts for men

http://www.cheapairjordan.uk

nike roshe uk

nfl jerseys from china

kobe shoes

michael kors outlet

fitflops outlet