The end of summer vacation is a bitch, full of much gnashing of teeth and tearing of hair, and many many little anxiety attacks.

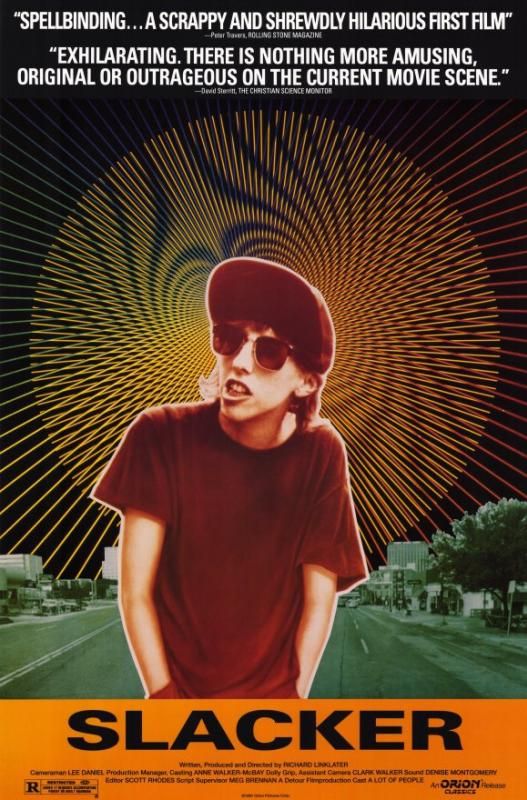

Slacker

1991

Director: Richard Linklater

Starring: um… Austin, Texas

Technically

speaking, I am part of Generation X.

However, I am on the tail end of what chronologically defines Gen X, and

I grew up with enough awareness of the term to understand all the negative

connotations that go along with it. The

characters in Slacker are full on Gen X, no doubt at all, and watching it

makes me feel oddly nostalgic for the early days of The Real World. I shudder,

though, that this film represents a generation with which I am technically a

part.

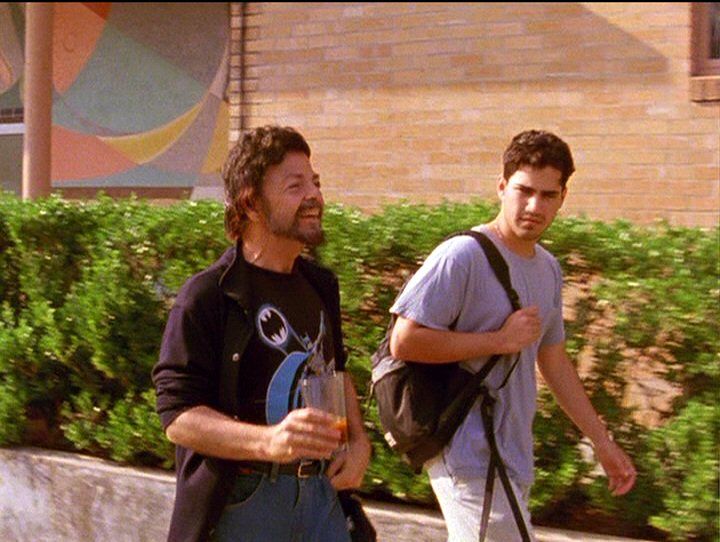

Slacker isn’t so much a story as it is

a conceit: it is essentially a series of vignettes strung together by

coincidence set in the city of Austin, Texas.

We watch a few people, who are almost always young, unemployed, and

pseudo intellectuals, as they have a conversation. After a few minutes, one of the group leaves

the conversation and the camera follows and moves on, finding a new

conversation and a new group of young people.

This continues as we spend our whole day meandering around the city,

jumping from group to group. There are conspiracy

theorists, nutjobs, anarchists, New Age gurus, and lots and lots of ramblers.

I’m

not a huge fan of this movie, but it has its moments, most of which I find a

bit blackly comic. I’m particularly

amused by the conspiracy theorist, credited at imdb by the role “Been on the

moon since the 50s.” His utter

conviction and nonstop spouting made me smile, as did how easily he passed from

having a discussion with one young man to having it with entirely different

people. Next up is the young man who’s

honest enough to pay for his own newspaper walking into what is easily the most

bizarre diner where a patron yells at him to “stop following me!”, the owner

tells him to “cut it out!”, and the woman at the counter tells him it’s

inappropriate to sexually assault women over and over. Poor guy… and he just wanted change for the

newspaper! Similarly, one of my favorite

sequences is when a would-be robber holds up a homeowner at gunpoint, only to

have that homeowner turn out to be a raging anarchist who not only talks the

robber down but seriously schools his ass.

The fact that the anarchist is an elderly gentlemen is just icing on the

cake.

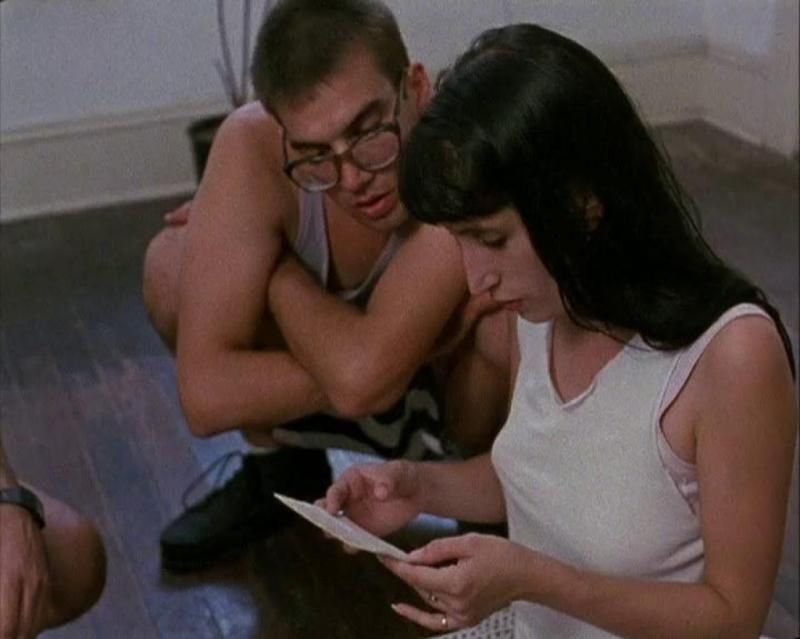

There

are moments of sympathy in Slacker as well, although they’re

few and far between. A young woman who

gives a quarter and a Diet Coke to a homeless man then tolerantly puts up with

a Kennedy wingnut’s ramblings and very kindly excuses herself without putting

him down in the slightest. A different

young woman makes a slanted illusion to having some fairly serious health

issues, and there is definite tension in her conversation with a young man, who

rather bluntly steps over her confession and begins talking about himself

instead. Every now and then, through all

the meandering conversations that seem to be going nowhere, there is a spark of

real emotion, a hint of real kindness or real pain.

But

for the most part, Slacker is full of void.

This is obviously on purpose, as it is a commentary on the “Slacker”

mentality that seemed to be the defining feature of Gen X in the early

nineties. Rambling conversations by

pretentious unemployed dicks about Dostoyevsky or the power of the video image

are so maddeningly vacuous that I wind up wanting to throttle half the

characters. And this is really my

biggest issue with Slacker; I wouldn’t mind the portrayal of this sort of

mentality as much if I myself felt more removed from it. I find myself in this odd duality, where I

know that I’m a member of Gen X, this generation portrayed here in Slacker,

and yet I feel absolutely no kinship with anyone in the story. I bristle that this is how “my” generation is

seen. And yet, maybe it was this

portrayal of my generation in the media at large that I grew up with that

helped me NOT become this. I remember

watching The Real World in the early

years, watching Clerks when it just came out on home video, and certainly I

remember how much everyone talked about Reality Bites. Heck, I even did a research paper in high

school comparing and contrasting Hemingway’s Lost Generation with Gen X. I was incredibly aware of this media

portrayal, and maybe, in some small part, it drove me to NOT fall prey to the

Gen X stereotype. After college, I

fucking went to grad school. I did

something, goddammit, I studied and worked in a research lab, then student

taught and got a goddamned career.

I

tend to be in favor of nonprofessional actors in films; usually they deliver

surprisingly effective low key performances because they’re not trying to

“act.” I’m not sure if the actors in Slacker

were nonprofessional or not, but if they were, then this could be the film that

puts me off nonprofessionals. The acting

is painful. PAINFUL. The conversations are already rather rambling

and awkward, and when you add on top of that awkward performances, it does not

make for an enjoyable experience. It’s

like watching an Amateur Improv night down at the local comedy club, and not

the good one that gets decent performers.

Just stop. Just stop right there.

To

end on a positive note, my favorite part of Slacker is also the most

incongruous. Linklater spends the whole

film rambling around aimlessly, following people so apathetic they’re hardly

breathing, and so then it is curious that he ends it with a segment that is the

antithesis of everything that preceded it.

As the film goes from a wingnut driving around in his car shouting

absurdities through his roof speakers, we suddenly cut to a group of young

twentysomethings out filming their day adventure on a Super 8 camera. They are happy – unironically happy, even –

as they traipse about and “Skokiaan” plays joyously on the soundtrack. These young people are doing something, they

are not moping about indoors simply talking about doing something. They are happy instead of lethargic. I choose to interpret this ending as

Linklater ending on an optimistic note, recognizing that not everyone in this

generation is as downtrodden as the people who inhabit most of Slacker. Is that what he’s really saying? Who knows, but that is the ending I need it

to be. I need a bit of energy and

happiness and optimism after an hour and a half of mind-numbing apathy.

I

like the central conceit of Slacker quite a bit, and it

definitely has a bit of nostalgic appeal as I remember growing up with this

sort of media representation of who I am supposed to be. But I am not this aspect of Gen X, and I have

never been that way.

Arbitrary

Rating: 6/10