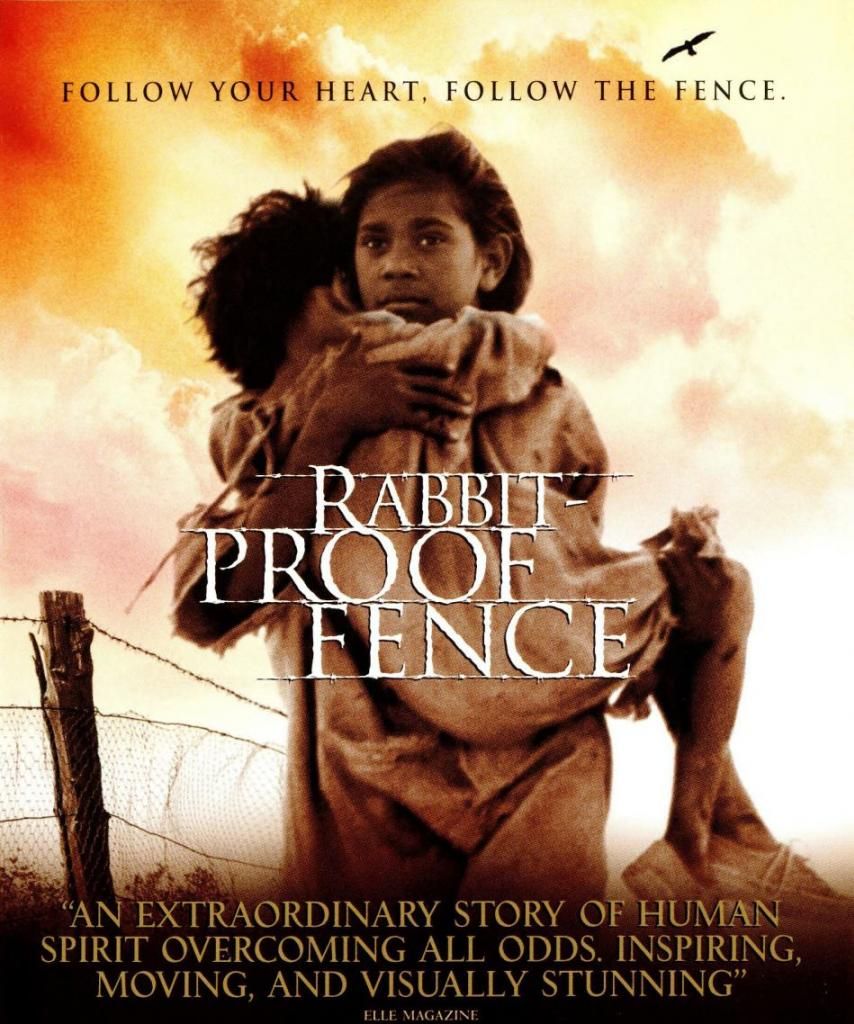

Rabbit-Proof

Fence

2002

Director: Phillip Noyce

Starring: Everlyn Sampi, Tianna

Sansbury, Laura Monaghan, Kenneth Branagh

Although

I am by no means an expert on Australian cinema, nor have I seen tons upon tons

of this country’s films, I *will* say that there is a certain sensibility to

many of the films from Australia I’ve seen that I really enjoy. Rabbit-Proof Fence continues in the tradition

of Walkabout,

Picnic at Hanging Rock, The Last Wave, My Brilliant Career, and yes,

even a bit of The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, in terms of

pitting man (or in this case, girls) against nature and drawing on just a hint

of otherworldliness along the way.

Three

“half-caste” (re: half Aboriginal, half white) children, Molly (Sampi), Daisy

(Sansbury), and Gracie (Monaghan), are taken away from their mothers in 1930s

Australia as part of A.O. Neville’s (Branagh) plan to “breed the dark out of

them.” The white population was in total

control of the Aboriginal population and felt it their duty to provide a

traditionally white upbringing to these “half-caste” children. Molly, though, is having none of it; she is a

clever girl, and escapes the settlement in order to return to her mother,

bringing her sister and cousin with her.

This involves a journey of 1200 miles on foot, following the eponymous

fence, which runs for thousands of miles across Australia back to Molly’s

mother’s home.

The

tension of this film is based on racial prejudices: the whites have cordoned

off the Aborigines. This theme has been

seen too many times around the world, but here in the States, we don’t hear

about many of these tales as often as we should. We only vaguely know about the struggles of

the indigenous peoples in Australia; it’s good to see a movie like Rabbit-Proof

Fence in order to be made more aware.

Although the concept of “The Stolen Generation” is still apparently

debated in Australia (by conservatives, so take that for what you will), what

is not up for debate is the racial prejudice behind such an idea. Watching Molly, Daisy, and Gracie being

ripped from the arms of their mothers at the opening of film is rough.

Given

that racial prejudices lead to such vile hatred, what sets the prejudices in Rabbit-Proof

Fence apart is the lack of outright hatred we see on the screen. This is personified by Branagh’s portrayal of

Neville, the man responsible for the concept of separating children from their

parents in order to “raise them correctly.”

Neville is clearly the chief antagonist, the man who plots and schemes

to keep the girls in their settlement and away from their mothers. But he is also completely convinced that he

is acting in the girls’ best interest by doing so. Here is a man so utterly committed to his

ideology that he honestly does not realize how morally reprehensible it

is. It’s interesting, then; Neville is

not so much hateful as he has an awful case of tunnel-vision. It’s rather like Tommy Lee Jones’ character

in The

Fugitive – not chasing Harrison Ford because he hates him, but because

it is his job, it is what he is supposed to do.

This is mirrored by the nurse at the settlement: she is stern, but also

a little kind. She honestly thinks she

is helping these children. It’s an interesting

concept of evil.

Necessarily

filmed mostly in exteriors, we get lovely, awesome, sweeping landscapes of

Australia throughout the film. Very few

scenes are indoors – in fact, most of the indoor scenes are those involving

Neville. This lends his character a kind

of claustrophobia, underlining how unaware or insensitive he is of the larger

world around him. Furthermore, what’s

nice about the scenery in Rabbit-Proof Fence is that the

exteriors are varied. It’s not simply

barren red desert for every scene. The

girls are making a voyage of over 1200 miles; naturally, their landscape would

alter along the way.

The

soundtrack to Rabbit-Proof Fence is very good, and one that I noticed right

away in my first viewing. Peter Gabriel

composed it, but he doesn’t go hog wild synthesizer cheesetastic (as he is

sometimes wont to do). There’s a

restraint that builds a haunting sense of isolation. Naturally he uses many native Australian

instruments (take a shot every time you hear a didgeridoo), and he can’t help

but sneak some synthesizer in there a little, but he focuses on

percussion. The beats, the rhythms are

the important aspects in this score, not a melodic theme. The score provides the heartbeat of the film.

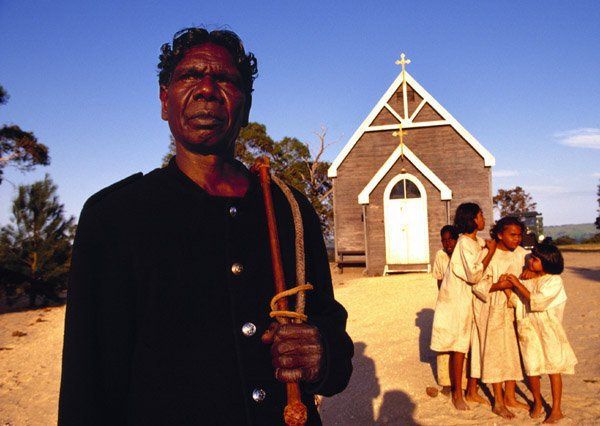

|

| He's one badass mofo. |

I

smiled so broadly when David Gulpilil first appeared onscreen. Given that I like many of the Australian

films I’ve seen, and referring to those specifically mentioned in my opening

paragraph, casting Gulpilil is not only awesome, but it feels right, almost

necessary. Gulpilil, in all his

awesomeness, plays Moodoo, the crackerjack tracker Neville sets on the

girls. Moodoo never fails to return a

runaway, and he can read the landscape like a pro. Molly knows this, and she is immensely clever

in her planning and her trek; she must be, in order to outwit Moodoo. What I found enjoyable was watching Moodoo’s

respect for his prey grow throughout the film.

Indeed, in some scenes, I was uncertain whether or not Moodoo knew

exactly where the girls were, but refused to say. Gulpilil is an actor whose performance comes

from his presence rather than his words.

He can be a bit stilted reciting dialogue, but he’s awesome with

piercing stares and otherworldly charisma.

In the making-of documentary on the DVD, the three girls who played the

leads were shown Walkabout prior to their meeting Gulpilil (I wonder if they

were shown the end). There is a sense,

especially if you consider Walkabout, of the torch being passed

between generations of Aboriginal actors.

Ultimately,

though, Rabbit-Proof Fence is a tense and dramatic film that makes for

good watching. It easily pulled me in

and got me emotionally invested in the plight of these girls. Cracking good yarn!

Arbitrary

Rating: 8/10