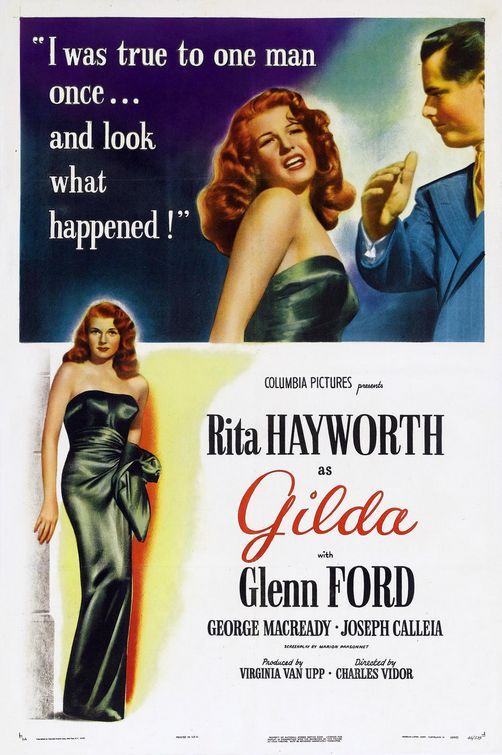

Gilda

Director: Charles Vidor

Starring: Rita Hayworth, Glenn Ford,

George Macready

1946

The

movie that turned Rita Hayworth from a starlet into a star, Gilda

drips with venom-laced sex appeal at every corner. It’s a noir – of sorts – and also provided

Glenn Ford with one of his most iconic roles.

Self-loathing and sexualized hate underpin most of the motives in the

film, and it’s so rampant, so out-of-control, that if this film had a

temperature, it would be too hot to handle.

Johnny

Farrell (Ford) is plucked from his street rat existence by the smart,

sophisticated and wickedly cunning casino magnate Ballin Mundson

(scene-stealing Macready). When Farrell

meets Mundson’s new wife, Gilda (Hayworth), memories of what had to be a

passionate but toxic love affair with the woman in question resurface. Mundson, no fool, sees these sparks of

hate-filled passion fly, and thus begins one of the most venomous love triangles

in all of film.

The

first time we see Glenn Ford, the “hero,” for lack of a better word, he is down

on his hands and knees, anxiously picking up some die from a gambling

ring. Slovenly, underdressed, he is a

ramshackle of a man. He nervously grins

and glances at the shoes that surround him as he collects his dirty winnings as

hurriedly as he can. Farrell will come a

long way from here in the story, but his cheating, soiled, grubby beginnings

will follow him forever. You can clean

the man up but you cannot turn him into a gentleman. He is perpetually reminded of his lowbrow

upbringing; his boss looks down his nose at him; the bathroom attendant

constantly calls him a “peasant.” He is promoted quickly to a manager of

Ballin’s casino, yet he has no real handle on his employees, no sense of

control, no real power. He is not let

into the innermost workings of the place, he is left to wonder about its

secrets. Perhaps, due to his lack of power

in his own life, his pretensions at grandeur, he lashes out by trying to control

Gilda. She is the only thing in his life

– yes, thing – that he can have some sort of power over. This isn’t to say that Gilda won’t fight this

control wildly, but he’ll exert it nonetheless, acting on the frustrations of his

class consciousness, with one of the cruelest fists ever attached to a “hero.”

Once

again, Rita Hayworth is inescapably luminous.

I have a burning love for her, similar in nature, I am sure, to many men

of the forties and fifties. She is so

open and yet so unknowable in this film; artless and simple, and yet capable of

cruelty and hate. Gilda is the

quintessential woman who is battered by fate, thrown back and forth and beaten

cruelly by the wills of the two men who, well, at least claim to love her. What sets Gilda apart, what makes her more

than a waif adrift in the wake of fortune, is the fact that this waif has a

backbone. And claws. And, most amazingly for the forties, an acute

awareness of her sexuality. Gilda likes

her husband, and Gilda loves Johnny, yet the world is angry at her and decides

to punish her. She lashes out by viciously

flirting with whatever stupid man happens upon her track. She knows, all too well, that Johnny is still

in love with her, and to get back at him for what is most likely a history of

mistreatment, she decides to torture him.

Torture, slow and acute, not by physical pain, but by sexual

prowess. Pitch perfect when she is

punishing him, this Gilda is counterpointed by the Gilda who never actually

went through with her flirtations, the innocent, open Gilda, the one who

finally admits she still loves Johnny, the one who plaintively sings “Put the

Blame on Mame.” Undoubtedly, this is

what made Rita Hayworth an icon, and this, her most iconic role, for in one

movie, she manages to be both the angel and the whore, and don’t men really

want both?

The

misogyny in the film is wildly rampant.

I would even call it the central theme.

Both Johnny and Ballin clearly hate women. Johnny is wildly, passionately in love with

Gilda. So what does he do about it? He calls her vicious names, he ruins her

reputation, he marries her then locks her up in his room. Ballin loves Gilda – well, he certainly likes

her enough to marry her on a whim – and what does he do about it? He uses her as a pawn, pushing her together

with Johnny then taunting the two of them for it. He views her far more as his possession, as

if he went into town one day for some eggs and bought a wife as an impulse

purchase at the register. For all of

this mistreatment, this film still appeals to me (despite my just beneath the

surface rampant feminism) because Gilda is not stupid enough to take it. She’s a smart girl, and when treated badly,

she’ll treat them badly right back.

She’s surrounded by misogynists, yet even though she’s mired down by

their hateful webs, she’s struggling to get out, fighting tooth and nail to

free herself. I just wish that she had

been smart enough in the first place to avoid getting involved with such

horrible men.

The

setting fits in nicely with Hollywood’s South American obsession of the

thirties and forties. In terms of

“exotic locales,” one really couldn’t beat South America at that time. Not actually shot there, of course; why

bother when a backstage will do? Notorious,

Now, Voyager, seemingly half a dozen Fred and Ginger movies, and that’s

just to name a few of the films that viewed South America as some mysterious,

fascinating vacation land the characters could jet off to, escaping their

mundane lives. Gilda is yet another film

looking for some sort escape. In this

film, the escape is from law and justice; the dirty casino needs to operate

outside the boundaries of legal limits and to allow some plot-thickening former

German scientists (re: Nazis) to distract from the central triangle. The lawlessness that abides and the lack of a

judicial system are the intrigues of South America here. The artificiality of the sets, however, so

clearly not in South America, adds to the hyperrealism of the story, somehow

reminding the viewer that this story isn’t real – how could it be? The people are far too vicious.

Considered

a noir by some, Gilda is one of those films on the edge of genre classification. It is noir in some aspects, but not all. In terms of characterization, I have no doubt

that this film fits nicely within the genre.

People with horrid motives – money, lust, greed, possession – these are

the people who populate the world of Gilda. In my opinion, you cannot call a film a noir

without these things. Also helping the

argument is the camera work. Not nearly

as replete with canted angles as, say, The Third Man, Gilda does dabble now

and then in the play of shadows and smoke.

In one gorgeous scene, Hayworth, clearly feeling vulnerable and small,

has her head practically obscured by her pillows and hair on her bed, and she

is completely in shadows. When she

speaks, we cannot see her lips moving, so it is as if the words are being

superimposed on the shot.

The sets,

however, are too glossy, too glamorous. We see little to none of the seedy underbelly world of crime that is

important to the look of the noir style.

Gilda looks like noir-lite, almost, as if Hollywood didn’t want

to get its hands TOO dirty when making the film. Furthermore, there is the question of the

ending. Noir films are about fatal

flaws, key term being “fatal.” Can a

film noir have a happy ending? Does the

ending undo the noir characterizations the film spent so much time

establishing? In my opinion, it

doesn’t. The ending feels a bit too

artificial, just like the nightclub sets, and I choose to interpret it as not

the ending to Johnny and Gilda’s story, but more a continuation. These two people, who spent so much time

torturing one another, can they really end up happy with one another? Doubtful, and it is this doubt that leads me

to believe, personally, that this is a noir.

All

the unnecessary frills that surround the central triangle are mere

distractions, as that triangle is the true strength of Gilda. Three people who simultaneously love and hate

one another. Hayworth, still underrated

to this day in regards to her acting ability, is absolutely marvelous and

manages to carry a film about such horrid relationships, turning it into a

truly iconic piece.

Arbitrary

Rating: 10/10. I don’t think it’s a

perfect movie, but I really really really effing love this movie. One of my all-time favorites.

Good review. In regards to the noir question, I don't consider it to be in that genre. You may be right about what will happen after the movie ends, but if people thought through most movie endings they would come to similar conclusions. A more modern example is the much loved by women Say Anything.

ReplyDeleteSPOILER WARNING FOR SAY ANYTHING

If you think about what happens after that film you realize that it won't take too many months for the girl to get sick of the guy hanging around her college, trying to get some of her time, while she is discovering all kinds of fascinating new things and fascinating people that are much closer to being her intellectual peers and that share her interests. And we know the guy, despite how charming he is, is probably never going to hold down a steady job; he'll just end up living off her, with her funding one crazy scheme of his after another, if they even manage to stay together long enough for her to graduate.

But who wants to think about things like that? Most people just want the "happily ever after" that the movie gives them.

I love it. Nice dismantling of Say Anything. Say Anything is a film that many women around me get all giddy over. I like it, but I agree with your assessment of the ending. I very much identified with the female protagonist - I was that supersmart overachiever in high school and college, maybe not to the same degree as her, but enough to make me really side with her. I was not really attracted to Lloyd Dobler at all, and I don't understand the appeal. So yes, I agree with your reading of that ending.

DeleteAnd to address Gilda in particular, as I said, I think Gilda is a bit on the edge of the classification. For me, it's a noir because of the horrid love triangle and all kinds of psychosexual torture inflicted by the three leads, but I admit it lacks a bit of a visual fingerprint, and then there's the ending.

MEGA GIGANTIC SPOILER WARNING FOR SAY ANYTHING AND BLUE VALENTINE!!

DeleteSo there's some talk that Blue Valentine of a few years ago is actually something of a sequel to Say Anything. Watch it, and you'll see exactly why that makes sense. It's a legitimate place for that relationship to go.

I think of Say Anything as a manic-pixie-dreamgirl film, except for two things: first, Lloyd is a manic-pixie-dreamguy and second, it's from his point of view instead of from the point of view of the person who falls for him.

As for Gilda, I totally buy that relationship. The tungsten cartel loses me completely. I think it's needlessly complex because of that subplot, and ends up being flawed, but beautifully so.