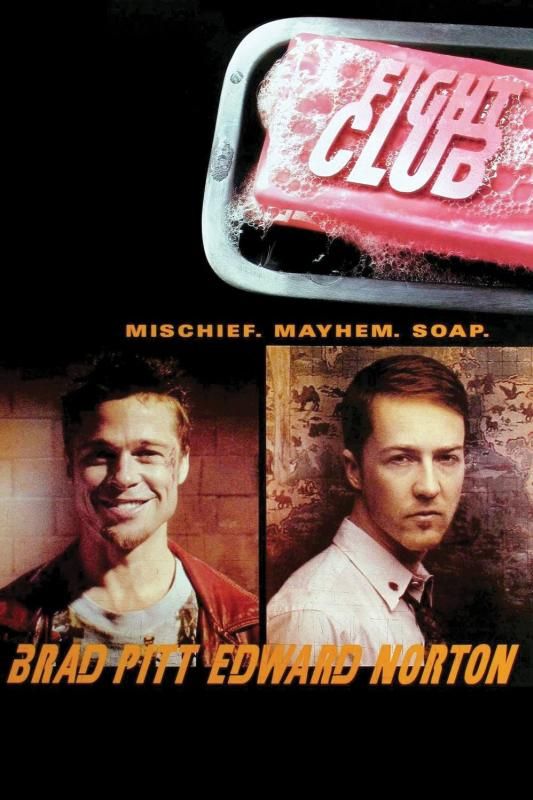

Fight

Club

1999

Director: David Fincher

Starring: Edward Norton, Brad Pitt,

Helena Bonham Carter, Meat Loaf

Okay,

let’s get this out of the way right now: I just watched Fight Club for the very

first time two days before writing this review (ETA: which was, in fact, about

a year ago, it just took me awhile to post this review, because that’s how I

roll, yo.)

“What?”

“OMG!” “You’ve NEVER seen it before?” “What’s wrong with you?” “BEST MOVIE

EVER!”

There. Is that out of your system now? Good, I may continue with my review.

Fight

Club

pissed me off, but not in the way you’d think.

It pissed me off because as I was watching it, I kept on thinking of how

damn GOOD it is. How, cinematically

speaking, it’s both accessible and daring.

And then I remembered that it’s fundamentally a GUY movie. You know, a guy movie – guys love it, girls

hate it. Dark, gritty, lots of guns and

violence, very few female characters.

And

that made me mad.

Because

the best of the guy movies are awesome.

Seriously, spectacularly awesome pieces of cinema. In the last twenty-five years, guy movies

have given us Seven (same dude, yes, I know), all of Christopher Nolan’s

films (Memento, Inception, The Dark Knight), Donnie Darko, Goodfellas,

etc. What fantastic films. And guys love them. They are not hard films to love.

What

are the “great chick flicks” of the last twenty-five years? Titanic? Vomit.

The Princess Diaries?

Are you serious? Under

the Tuscan Sun? Passable at

best. I can get behind Notting

Hill, but Notting Hill is not a cinematic masterpiece. I mean, it’s awesome, but in a “I can turn

off my brain now and the movie will amuse me” kind of way. It’s hardly challenging.

The

best guy movies ARE challenging. The

best recent chick flicks… well… aren’t.

And

that made me mad.

Because

Fight

Club is such a great cinematic work, and it’s so fundamentally

masculine, and chick flicks are shitty.

Why

are chick flicks so shitty? Why does

Hollywood think that women are content to settle for utter rubbish as long as

there’s a hot guy walking around half naked?

Ladies, here’s a hint – Brad Pitt walks around half naked in Fight

Club, and this movie is much more worthy of your time than, say, Letters

to Juliet.

Oh,

right, I should probably try to review Fight Club rather than just rant

about the dearth of quality “female films” being made in Hollywood. It tells the story of a desensitized,

insomniac insurance claim investigator (Norton) who meets childish and arrogant

soap salesman-cum-explosives expert Tyler Durden (Pitt). Together, they form the eponymous Fight Club. Marla (Bonham Carter) takes up with Tyler,

much to the chagrin of our narrator.

Things start to spin out of control when the men involved in Fight Club

start branching out from just hitting each other.

For

my money, the first half hour of Fight Club is perfect. Sheer, cinematic perfection. It’s funny, it’s witty, it’s engaging, and

it’s damn unique. Just when you think

you know what’s coming, David Fincher spins the film in a completely new

direction. There’s voice-over narration

that blends seamlessly into actual dialogue.

We go from Marla and Norton bickering over which support group the other

“gets,” to vibrating dildos in airline luggage, to Meat Loaf’s “bitch tits,” to

what you’d name a tumor if you had one.

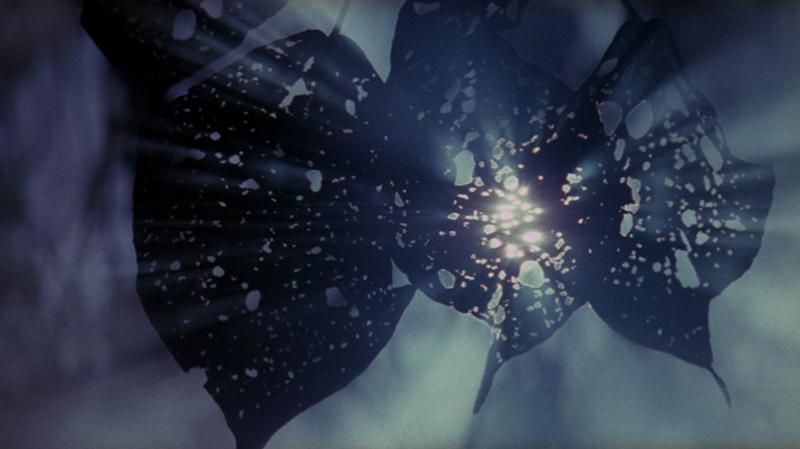

The camerawork is dizzyingly fresh, zooming through gas lines or up and

down a waste bucket, places we wouldn’t expect to see. The fourth wall gets broken during a brief

scene that is so unexpected and so funny, you can’t help but smile. The film even opens at the neural synapses of

the brain and zooms out to Norton’s face, a journey which is disconcerting and

takes awhile to place. The first half

hour, man. It’s so unlike other

films. It’s so entertaining. It’s funny and sharp and unique. It’s perfect.

The

rest of the film is very good, but it’s not like the first half hour. With the formation of the actual Fight Club,

the film becomes more traditional in its narrative (or rather, as traditional as

an out-there story like Fight Club can be). The ingenuity shown in the filmmaking process

of the first thirty minutes gives way to much more straightforward

storytelling. I suppose, in a weird way,

it would have been far too exhausting to create a film that was as off the wall

as those first thirty minutes.

Accompanying

this shift in technique is a marked shift in tone as well. The film becomes significantly darker and

bleaker as we go into more traditional movie mode. It’s interesting rewatching Fight

Club (yes, this means that I’m watching it twice in two days;

rewatching helps inspire me when I write about a movie) and remembering just

how funny it starts, and just how dark it becomes. The narrative is driven to a very frightening

place; things go wrong, and it seems as if nothing will ever go right. Unfortunately, I also feel that, despite the

intriguing social commentary, the film starts to feel water-logged. It gets a bit too heavy, a bit too

dreary. It starts to lag, pace-wise. It can’t keep up with the fresh and fast pace

of the opening. That being said,

Fincher, at the very last moment, brings Fight Club back from the edge of

being the most depressing tragedy you’ve seen in awhile and reiterates that

what you’ve just watched is, in fact, a comedy.

Technically speaking, in the most basic of all dramatic terms, the

difference between comedy and tragedy hinges on death, and for most of the

central story of the film, we seem to be careening toward the chasm of

tragedy. There’s funny stuff in the

first third, but it becomes so dark and heavy, the “comic” ending feels

unnatural for most of the film. I

understand it, though. It’s bringing the

movie full circle, back to the significantly lighter comedy of the

opening.

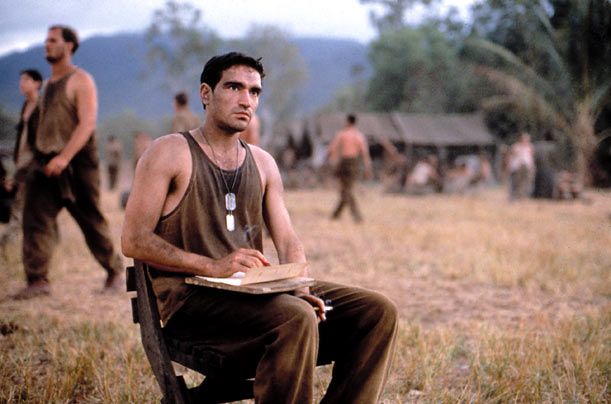

The

two leads, Norton and Pitt, are fantastic.

Norton, as our lead, is the one who takes us on a journey from trapped

office worker to rebellious fighter to frightened desperado, and, in what I

have come to expect from Edward Norton, is phenomenal. He’s funny when he needs to be, he’s pathetic

when he needs to be, and more than anything, he’s believable. Dancing around him are the two crazies of

Brad Pitt and Helena Bonham Carter. Pitt

is the embodiment of the id, easily flaunting society’s rules by only doing

what feels good, then literally rewriting the rules of civilization. While I don’t think his work here is better

than his role in Twelve Monkeys (because I love Twelve Monkeys… which I

just realized is probably a “guy movie…” dammit…), Pitt does his half-naked

crazy dance well.

There’s

a hyperrealism to the photography in Fight Club that manages to make the

movie both ugly and beautiful, real and unreal, all at the same time. Everything looks like things we know. The pay phone is a pay phone. It’s scratched and dirty, like a real pay

phone. But then the camera zooms up

close, closer than we expect, and the scratches keep getting thrown into more

stark relief, there is more detail than you could possibly have imagined. The film is full of photographic touches like

that; familiar things shot with such excruciating detail that they become

artificial.

There

was a surprising amount of fairly accurate chemistry in the movie. (Yes, I am

now about to nerd out about chemistry.

Brace yourself.) For the record,

as a chemistry teacher, every year I teach the definition of

“saponification.” (the making of

soap) And nearly every year, I’ve had at

least one student say, “Oh, like in Fight Club!” Now I can respond with a tangential

discussion of how great the film is, huzzah!

There’s a scene with a chemical burn (I’m guessing it was some sort of

hydroxide) that was painful for me to watch because a) I have firsthand

experience with chemical burns and b) I actively spend my days trying to

prevent such things happening to my darling little students.

|

| Seriously, you guys, this scene made me cringe because it's exactly what I DON'T want happening to all my lovely little students... |

For

a film titled Fight Club, I was bracing myself for a level of violence that

was damn near unwatchable. Apparently,

my hypersensitivity to violence is mostly confined to war films, because I was

surprisingly accepting of the violence in this film. There is no shortage of deep purple fake

blood and plasma, to be sure, and the sound of flesh thwacking against cold

hard concrete is distinct and a little stomach churning, but the violence is

also not nearly as nonstop as you would imagine. The focal point, the main message of the

film, is much more about eschewing society’s rules (and possible repercussions

therein), and much less about violence for violence’s sake.

Fight

Club would

make a great double feature with Office Space, made the same

year. I am CERTAIN I am not the first

person to associate these two films together, but they both deal with a central

character who, tired of the cubicle life, starts to break free from American

cultural expectations. Fight

Club makes its point with wild violence and hyperbolic

antiestablishmentarianism gestures. Office

Space makes its point with funny gags and a red stapler. Two drastically different comedies, but an

intriguing double feature. At the very

least, I anticipate such a double feature would have you wishing you could

properly tick off your boss more.

Or,

in my case, it would make me angry about why guy films are so intriguing and

chick flicks are so braindead.

Arbitrary

Rating: 9/10. Ironically, considering

the overall message, I think the film starts to run out of steam in the second

half. But that doesn’t stop the whole

movie from being AWESOME!