The

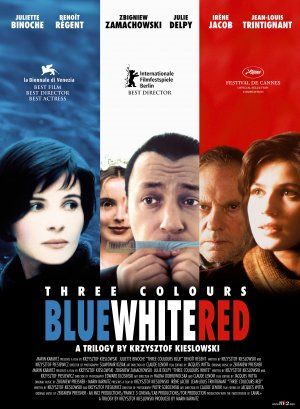

Three Colors Trilogy: Blue, White, Red – Happy Birthday, Krzysztof Kieslowski!

1993-1994

Director: Krzysztof Kieslowski

Starring: Blue: Juliette Binoche,

Benoît Régent White: Zbigniew Zamachowski, Julie Delpy Red: Irène Jacob,

Jean-Louis Trintignant, Jean-Pierre Lorit

At

the end of his career (and life), Kieslowski made this trilogy of films that

are nominally (and only nominally) focused on the themes represented by the

three colors in the French flag: Blue for Liberty, White for Equality, and Red

for Fraternity. Having made the highly

successful Decalogue film/mini-series (ten separate “episodes” about

residents of an apartment complex, each episode dealing with one of the Ten

Commandments), it is easy to see why Kieslowski was similarly drawn to a series

of films linked in concept. These three

films turned out to be his final work, as he died two years after filming Red. What a testament to leave to the world of

cinema.

In

Blue,

the first of the three films, Juliette Binoche (in a stellar performance) plays

Julie Vignon, a woman who has recently lost her husband, a composer, and young

daughter in a car accident. She deals

with this tragedy by attempting to shut herself off from the world. She sells their house, their possessions,

everything – she wants no reminders of her once happy life. She seems angry when vestiges of her former

life try to creep back in. The film is

very much about her healing process after the tragedy.

In

White,

Zbigniew Zamachowski plays Karol Karol, a Polish hairdresser whose young wife

Dominique (Julie Delpy) is divorcing him for failure to consummate their

marriage. She not only divorces him, but

freezes his bank account and locks him out of their home and business. He is left with less than nothing but his

continued love for his ex-wife. He

retreats to Poland where he builds up a somewhat shady business empire, then

stages an elaborate ruse in order to get revenge on his ex-wife for her bitter

treatment. The film is a dark comedy.

In

Red,

Irène Jacob plays Valentine, a young student and model in Geneva who, through a

series of events, meets a retired judge (Trintignant) who is spying on his

neighbors’ phone calls. The two form an

unlikely bond despite their age and gender gap.

Simultaneously, the film introduces us to Auguste (Lorit), a young man

studying to become a judge who happens to live right across the street from

Valentine. The two do not know one

another but are consistently shown just missing one another in their daily

lives. The film is (among other things)

a romance about the possibility of a relationship between Valentine and

Auguste.

It’s

an interesting trilogy in that it is three tremendously separate stories, not

connected by common actors, characters, or even genres. One could easily watch a single film from the

trilogy and enjoy it on its own, and never watch the other two. The three films function completely as

stand-alone films. However, there is most definitely a thread that ties all

three films together, and it is the central theme of human connectedness and

the concept of choices versus destiny.

SPOILER ALERT: While I typically avoid revealing spoilers, I

have thought long and hard about this and have come to the conclusion that the

points I want to make about Blue, White and Red hinge upon me

discussing the endings of the films. I

don’t normally like to do this, but the way Kieslowski uses narrative is critical

to me in understanding his viewpoint of the world around him. I am terribly sorry to say, then, that if you

are interested in actually watching these films, and holy cow, are these

terrific films, please skip the next

section.

*************************************SPOILERY

BITS******************************************

In

the first two films, the main characters are desperately trying to sever

connections with other people. Julie in Blue

is desperately angry at the world and responds by cutting herself off from

it. The “Liberty” of the Blue in the

French flag is symbolized through Julie’s liberty – can she simply live? Can she have liberty from her former, happy

life, and reinvent herself as a single, lone person, dependent on no one? Ultimately, the film says “No.” (And this is

why I warn about spoilers.) Julie

ultimately lets people from her old life back into her world. She takes up her husband’s compositions. She allows herself to connect with other

people. She has spent the entirety of

the film fighting this, but ultimately, she cannot disconnect herself from her

life. It is impossible. Despite her choices, Destiny has other plans

for her, and she must allow herself to feel and love again.

Karol

in White

is similarly trying to disconnect himself from his ex-wife, Dominique. She has treated him so harshly, and has

easily disconnected from him, but his overwhelming love for her (bordering on

obsession) keeps him from forgetting her.

He wants revenge for her treatment, he wants his “Equality.” The ruse he plays is harsh indeed – he fakes

his own death, leaves her his shady business in his will, and then calls the

cops on her, letting her take the fall for his illegal dealings. She winds up in jail in Poland. Karol, having effectively gotten his revenge,

was then supposed to flee to Hong Kong and live out the rest of his life there,

happy in the knowledge that he got her back; however, he cannot do that. He cannot leave her. He loves her.

He cannot disconnect from her, and stays in hiding in Poland, visiting

the courtyard of her prison every day, gazing up at her barred windows. Try as they might, Karol and Dominique are

strongly connected to one another. They

were foolish to ever try to separate from one another.

In

Red,

the film is not so much about people attempting to sever connections, but

rather, the formation of new ones and just how deep those new connections are. Valentine and the old judge connect through

what one can certainly call Fate – she runs over his dog, and thus goes to his

house. There she is horrified to

discover he is calmly spying on his neighbors’ intimate phone

conversations. Despite all of this, she

keeps coming back to his house, usually drawn by the dog in question (who lives

– she didn’t seriously hurt her), and the subsequent long conversations between

Valentine and the judge show her that he’s not a perverted old man, just a

lonely old man. They form an unlikely

friendship, easily representing the “Fraternity” of Red in the French flag. All the meanwhile, the film plays with the

idea of the connection between Valentine and Auguste, the young

judge-in-training across the street. We

are constantly shown them in the same frame, nearly missing each other. These are two people who are almost connected to one another, but not

quite. Will Fate see fit to bring these

two people together? As Roger Ebert said

in his review of the film, “What a nice couple these two people would

make.”

Additionally,

not only is there the question about the connection between Valentine and

Auguste, but also between Auguste and the old judge. After all, Auguste is a judge in training, so

they share an occupation. Auguste and

the old judge both dress similarly and both own dogs. Kieslowski goes much further than that, however;

things get really funny when the old judge starts telling Valentine stories of

his youth, and wow, didn’t we see that exact same thing happen to Auguste about

thirty minutes ago in the film? We are

in her shoes when Valentine asks the old judge, “Who are you?” Are the old judge and Auguste one and the

same person? Is the old judge some sort

of omnipotent soul, looking beyond his timeline into both his own past, and

Auguste’s future? Is the old judge

reflecting on Valentine not as a new friend, but as a second chance at love, as

the person that he missed meeting in his youth the first time around? Is he trying to atone for his past blindness

by bringing Valentine and Auguste together in this new lifetime? Can he get Valentine and Auguste to actually

meet one another when they seem to keep missing each other? These questions are all incredibly tantalizing

and, I may add, make Red my favorite of the three

films.

Something

I truly loved about all three of these films, and what I hope to see more of

when I delve further into Kieslowski’s catalogue, is his subversion of the

concept of traditional film genres. In Blue,

a film most definitely representing tragedy and loss, we are not given the

typical establishing shots of a happy family.

We never see the “before” Julie, the Julie prior to the accident. We only know her after the accident. We follow through her healing process, which

is definitely intense and has moments of bleak sadness and long stretches of

depression, but the film most definitely ends on an upper. Julie has found a way to feel again. It’s a tragedy that, well, isn’t. Similarly in White, the comedy of the

three, there are certainly a few moments of broad comedy and plenty of moments

of dark comedy, but the film ends on a decidedly poignant and rather sad final

note. Karol has been unable to separate

from Dominique. We end the film by

seeing Karol gazing up at Dominique in her cell with tears streaming down his

face; not exactly a cheerful ending (although there is room for interpretation

there). And in Red, we are focusing on

the “romance” between Valentine and Auguste, and yet they are both involved

with other people. They don’t even know

the other exists. They spend the

entirety of the film separated from one another, only brought together in the

final moments of the entire trilogy, and only brought together through an

unspeakable tragedy. They don’t have a

“meet cute,” what you would expect after such a long, tantalizing buildup. They have a “meet horrific,” which, by the

way, we don’t actually SEE. We simply

see a news broadcast that shows the two of them together. We know they have met.

**********************************END

OF SPOILERY BITS***************************************

Ebert

commented on this genre subversion, calling Blue the “anti-tragedy,” White

the “anti-comedy,” and Red the “anti-romance.” I don’t know if I completely agree with

this. I understand what Ebert is trying

to say, but I don’t like his use of the prefix “anti-“ here. “Anti-“ means “opposite of.” An “anti-tragedy” would be the opposite of a

tragedy, which, in simplistic genre terms, is a comedy. Blue IS a tragedy. A woman is grieving. But it’s not a tragedy in the typical

play-out of a tragedy. White

and Red

are the exact same way – they are most certainly a comedy and a romance,

respectively, but they do not follow the predetermined paths of comedies and

romances. Kieslowski is smart, so smart,

he knows how to lead his audience down the primrose path and then take a hard

left turn. Honest to god, when I was

watching these three films for the first time, had absolutely no idea where the

films were going. They kept me on my

toes – and isn’t that a glorious thing?

Kieslowski

most definitely didn’t like giving the audience what it expected, and that was

wonderfully refreshing. For example, in Blue,

Kieslowski repeatedly uses a fade to black.

We, as the audience, have been trained to understand that the fade to

black represents the passage of time.

How disconcerting it is, therefore, to come back from his fade to black,

only to find ourselves still in the exact same scene. It as if the lights dimmed on the

conversation, only to come up on it again.

The first time he does this, I was completely caught off guard. By the end of the film, I loved it. Kieslowski is using classic film language in

a completely nontraditional manner. He

does this with editing and tone in Red.

When we first meet the old judge, the film is setting up everything

around him to convince us that he is “evil” or “a bad man.” We do not like him. He is threatening. Soon, the judge moves from threatening to

romantically interested in Valentine – or is he? Kieslowski keeps us guessing about his

intentions, which is precisely the point. Red is a romance unlike any other

romance, but it is a romance nonetheless, and ditto for the other two

films. Kieslowski gives us a tragedy, a

comedy, a romance, all done in a completely nontraditional manner.

There

is a distinctly political angle to the three films as well. Kieslowski was in favor of a unified Europe

(much like we have today, but one which is currently in danger of collapsing in

on itself). His outward portrayal of such

a Europe in Blue is a good 10 years before its time. Similarly, in Red, he sets it in

Switzerland but has characters in England and France, showing fluidity across

borders. Most notably, though, he shows

his political hand in White, which is good, because White

needs all the help it can get against the towering awesomeness of the other two

films. Poland was newly capitalist when White

was made, no more than two years after the Iron Curtain had been lifted. Karol’s relationship with Dominique can

easily be viewed as allegorical, with Karol representing Poland and Dominique representing

France. Poland, finally making the

switch to France’s ways, finds that France has abandoned it, and is suddenly

broke and crippled in the process. Man,

if that isn’t a political statement, I don’t know what is. Similarly, Karol viciously exploits

capitalism in the film, making a buck off anything and buying nearly

everything. He swoops in on a business

deal by pretending to be asleep in the back of a car. He buys land out from under the nose of his

boss in a rather slimy move, then sells it back to him at an enormous mark

up. Yes, Karol gets ahead in business

this way, but he’s not really being nice about it. And yet, that’s capitalism.

The

scores in the film are powerful. Considering

that music is a focal part of the plot in Blue, it makes sense that the music

is correspondingly thrilling. Highly

reminiscent of Beethoven, yet updated for the twentieth century, Kieslowski

uses it not only as background, but also as key plot points. The music is deep, soulful, and haunting;

everything you would expect to hear in a film about recovery from grief. The score in White has two very

distinct tones to it. In the first part

of the film, when Karol is being bullied by his wife, the tone is despondent –

naturally. The second he gets back to

Poland, however, the tone drastically changes, to a plucky spritely tune, and

it never changes back. It’s emphasizes

Karol’s commitment to his plans for revenge.

The score in Red gets increasingly tension-filled as the movie progresses

yet always maintains a sense of optimism and hope, much like Valentine’s

character. I was reminded of Ravel’s Bolero, a piece which builds in

complexity and power despite maintaining the same tempo and melody. It was an apt comparison.

There

is so much more to say about these three films – the lighting (which is

painfully beautiful), the color play (obvious, given the titles of the films,

but really cool all the same), the meaning behind the few scenes that link the

three films together, the concept of the god-like figure of the judge in Red,

but really, I think you can, by now, discern my enthusiasm for the films. I originally only borrowed Red

from my local library. I holed myself up

in our bedroom one night and watched it.

When it ended, my jaw was on the floor, and I proceeded to immediately

go downstairs and rant and rave to my husband about how amazing it was. It was so amazing, in fact, that I wanted to

watch it over again. Immediately, that

very night. I can’t remember the last

film I felt that way about; in fact, I’m not sure I’ve ever had that strong a

desire to immediately rewatch a film for the sheer joy of it. The very next day I went out to the library

again and borrowed Blue and White, and then watched the entire

trilogy “in order.”

These

films were the first of Kieslowski I have ever seen, and I am beyond intrigued

now. His powerful sense of humanity, of

interconnectedness, and of cautious optimism for the human race give these

three films a soul I have rarely come across in cinema before. I have not felt this enthusiastic over a new

film or films in a very long time. These

are something special. I cannot wait to

see more of his films.

Arbitrary

Ratings and final thoughts:

Blue: 10/10 – Binoche is

mind-blowing in the best role I’ve yet seen her in.

White: 8/10 – My least favorite of

the three, but comically poignant nonetheless and much stronger when its

political parallels are considered.

Red: Can I give this an 11? Wait, it’s my review, so I can? Awesome.

11/10. Beyond perfect. Raises tantalizing questions about fate and

destiny all the while being incredibly romantic. I love it.

My new favorite film, and I don’t say that lightly.