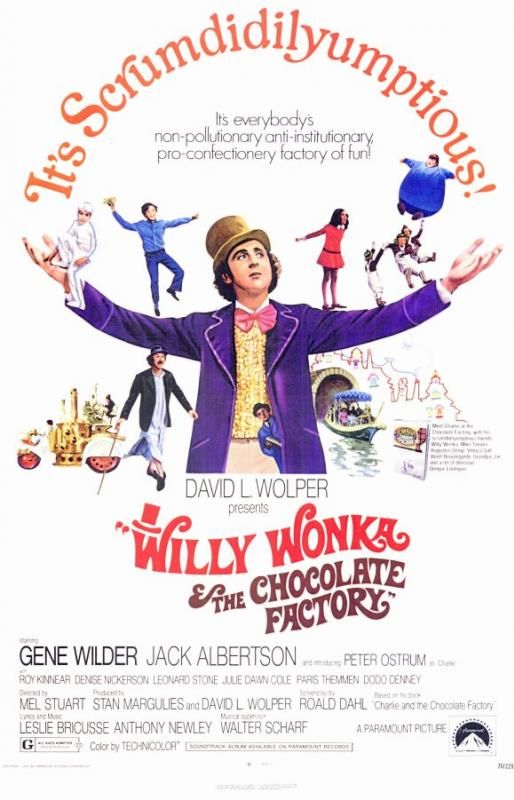

Willy

Wonka and the Chocolate Factory

1971

Director: Mel Stuart

Starring: Gene Wilder, Jack Albertson,

Peter Ostrum

Who

didn’t love this movie as a kid? Filled

with chocolate and candy and the most bizarre factory ever committed to film,

it’s a child’s dream. The opening credit

sequence, with shot after shot of ooey gooey chocolate, is enough to make my

mouth water just from the thought.

However, unlike most movies that you love as a kid, this one manages to

stand up to the transition to adulthood.

Charlie

Bucket (Ostrum) is very poor. When the

fantastic and reclusive candy maker Willy Wonka (Wilder, in perhaps his most

iconic role) announces a contest to win admittance to his factory and free

chocolate for life, Charlie is elated, and after being initially disappointed,

finds one of the five elusive Golden Tickets.

He and his Grandpa Joe (Albertson) encounter a myriad of wondrous and

terrible things in Wonka’s strange factory, but ultimately, Charlie proves he

is a good child, pure of heart, and wins Wonka’s final prize.

Based

on the famous children’s novel by Roald Dahl, Dahl also penned the screenplay

for this, the first adaptation of his work.

Dahl’s novels, favorites of mine when I was young (really, who DIDN’T love

his work?), are all bizarrely supernatural stories, where everyday children

somehow become involved in extraordinary events. What sets his stories apart from all the

other children’s novels about the supernatural, though, is Dahl’s supremely

honed sense of the sinister. Dahl’s

works don’t shirk from fear, realizing instead that it is important children

encounter safe manifestations of their fears in order to learn to deal with

them. I was fascinated by Dahl’s work

for that very reason. He wrote the best

villains. The Witches is

indelibly inked in my mind, despite the fact that I haven’t read the work for

two decades, because of its completely terrifying and thus effective villains.

I

mention all of this to make a point about Willy Wonka. It’s a children’s movie that transcends most

other children’s movies because of the fear, the threats, the sinister nature

of the film. Wait, isn’t it about

candy? Well, yes, but it’s more than

that. Willy Wonka focuses on a fantasy

world that happens to be built around candy.

Unlike most children’s films’ fantasy worlds, this is a world where the

rules are not only capricious but possibly vicious. There is evil and danger lurking even in the

most beautiful, candy-colored room, which, in turn, creates an atmosphere of

unease. There is great delight in the

film - I don’t want to paint this as an evil movie – but the delight is heavily

counterbalanced by a palpable sense of danger.

The psychedelic and dangerous boat ride is proof enough of that, let

alone the fact that Charlie is initially approached outside Wonka’s factory by

a man with a cart full of knives!

The

danger, the unease, the viciousness are all embodied and channeled through the

film’s main character, Willy Wonka. In

this role, Wilder fully inhabits his character in the most unnerving of

ways. It’s telling how strong of a

performance it is when you consider that Wonka himself does not appear until

nearly halfway through the film. He is

absent at first, but then his presence is so conspicuous, so all-consuming,

that you leave the film thinking he was in absolutely every scene. Wilder’s Wonka is an evil genius, an insane

criminal mastermind, but one who cloaks his crimes under the pretense of

selecting morally good people over morally bad people. When a criminal selects for the good and

against the bad, we don’t consider him a criminal, but when selecting against

bad people involves plunging them down pipes, sending them off to a gigantic

juicer, or pushing them through to an incinerator that may or may not be fired

up that day, he’s still a criminal. Wilder’s

Wonka is wily, slippery, and profoundly temperamental. He is singing one moment, and yelling the

next. He has next to no patience for his

guests, and is supremely unconcerned about any negative consequences of their

actions. How odd that he is the star,

then. He is far more a puppet master

than a hero; but, after all, that is what makes this movie so interesting. A dark, mischievious Puck-like figure at the

helm of an entire world is wonderful, thrilling, and frightening, all at the

same time.

Undoubtedly,

Wonka is the central figure of the film, but as mentioned earlier, he does not

make his first appearance until about 45 minutes in. The first portion of the film, often

overlooked in favor of the bizarre candy factory segment, deals with the

world’s search for Wonka’s Golden Tickets.

This section of the film is undeserving of its relegation as “second

best” half, as it’s uproariously funny. A

series of absolutely delightful vignettes about the fervor of the search paint

a portrait of a world absolutely obsessed with Wonka and his candy. A rich woman’s husband has been kidnapped,

and the ransom demand is a box of Wonka chocolates; she must think about it. A computer expert designs a program to tell

where the Golden Tickets are, only to have the program tell him he is

cheating. A psychiatrist is disdainful

of his client until the client says he dreamed the location of a Golden

Ticket. All these whimsical

mini-stories, completely unrelated to the overall characters’ stories, serve as

charming build-up to the entrance to the factory.

|

| I am now telling the computer EXACTLY what it can do with a lifetime's supply of chocolate... |

The

songs in the film are almost all ear-worms of the worst kind, guaranteed to be

stuck in your head all evening long.

“Who can make the sunshine?” you’ll hum, imagining Bill the candy

merchant in his wonderful little corner candy shop. Or maybe you’ll joyously sing along with

Grandpa Joe when he exclaims, “I’ve got a Golden Ticket!” Then there’s the Oompa-Loompas, the charming

yet also slightly fiendish workers at Wonka’s factory that serve as the Greek

Chorus of the film, singing “Oompa, Loompa, Doompity Doo.” Or best of all, sing along with Wilder as he

belts out, “If you want to view paradise / Simply look around and view it!” in

the beautiful “Pure Imagination.”

Infinitely singable, and very fun.

The

sets are pure whimsy. Wonka’s factory

was constructed entirely on backlots, lending a superficiality to it which

works. There isn’t meant to be anything

natural about Wonka’s factory, so it’s fitting that it all looks fake. The colors are bright and bold, and there are

oddities around every corner. The

lickable wallpaper (“The snozzberries taste like snozzberries!”), the

seizure-inducing room full of angles and dizzying walls, and the shrinking room

are only shown for a few moments, but they’re more than memorable. And, it’s worth mentioning, this was all

achieved without reliance on CGI special effects.

Last

November, the Dryden showed Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory;

that, in and of itself, is not so unique.

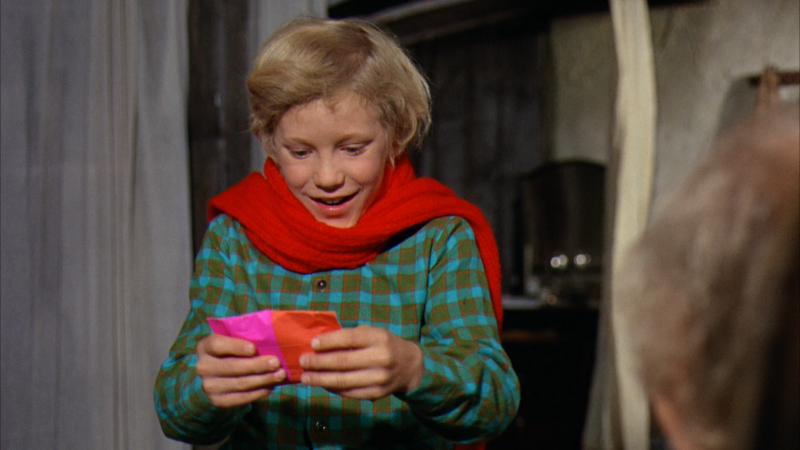

What was special was the fact that Peter Ostrum, aka Charlie Bucket,

attended the screening and spoke about his experience making the movie in

Munich. Ostrum is currently a large

animal veterinarian living and working in upstate New York; Willy

Wonka was the only film he ever made.

He struck me as a very humble man, and at the conclusion of the evening

said, “I was only in one film, but what a film it is!” He was very appreciative of everyone who

helped him on the set of the film, but also never regretted the decision to

leave acting.

|

| Ostrum told us the white goop in this scene was flame retardant foam from fire extinguishers. |

The

crowd that night at the Dryden was one of the largest I’ve seen in the six or

seven years I’ve been going there.

People were pumped to see this movie; much more than for typical movies. The excitement in the air was palpable. The audience actually applauded when the film

started – unusual, even for the Dryden.

Everyone watching the movie was SO into it, SO happy, SO excited, that

the entire audience broke out in spontaneous cheering and whooping when Charlie

found the golden ticket. It’s an easy

bet to make that the majority of audience members had seen the film before, and

therefore knew what would happen, but everyone – myself included – was so much

more excited about Charlie finding his golden ticket! It was a magical movie moment, just a part of

an evening that ranks high in my “Top Movie Theater Experiences” list.

I

loved this movie as a child, and I love it as an adult, and not purely for

sentimental reasons. It holds its own as

a legitimate film, full of whimsy and menace, musical merriment and threatening

danger. Children can handle danger if

adults let them, and more often than not, they’re better for it. After seeing all the horrible things that

happen to the horrid, obnoxious little children in this film, I know I was more

inspired as a child to be good like Charlie Bucket, because maybe, just maybe,

I’d get to see Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory!

Arbitrary

Rating: 10/10

I can't argue with any of this.

ReplyDelete"Pure Imagination" might be the single greatest song/song performance in a film I have ever encountered, and that's saying a lot. It's also Gene Wilder's best, and that's saying a damn lot.

I also love just how damn quotable this film is.

"Pure Imagination" is the musical embodiment of the spirit of this film. It's fun but also a bit threatening and dissonant. "Candyman" may have been the big chart-topping hit to come from the film, but "Pure Imagination" is the better song.

DeleteThis and Young Frankenstein are my two favorite Gene Wilder films, but Wilder, as an actor, is better here. He just has to be funny in Young Frankenstein, but here, he has a much more interesting job.

"I want an oompa-loompa nooooooooooooooooooow!"

You were very lucky to have been able to attend an event with Ostrum there to talk about the film. I've read that he makes very few appearances in relation to it and when he does they are usually ones geared towards children.

ReplyDeleteIf you have the DVD you have to listen to the commentary track by the five "children" (then all in their 40s). It's hilarious in places, especially when the two women get going. It may be the most entertaining commentary track I've listened to.

Yes, I definitely got the impression at the Dryden that this was not a normal thing for him. I think it helped that he works in upstate NY, and where I live/where the Dryden is located is western upstate NY, but upstate NY nonetheless. His whole family was there too, getting a tour of the George Eastman House (that's the museum the Dryden is a part of) beforehand. I think he said it was the first time one of his children was attending a screening of this film.

DeleteI'll definitely have to check out that commentary track, thanks! Wow, most entertaining? Impressive!

Just a further note on the commentary:

DeleteI've literally listened to several hundred commentary tracks. The best ones are by the actors, if there is more than one of them so they can get going trading stories; the worst ones are by the writers because they spend the entire time complaining about what was changed from their script. Producers tend to be second worst - they mostly talk about how hard it was for them to find locations. Directors can be hit or miss - some point out the little things they put on screen that you might have missed, while others just talk about the weather they had to deal with on every single shot.

Almost all commentaries are done "stream of consciousness" style with no preparation whatsoever. Warwick Davis' commentary for Willow is a big exception - he was thoroughly prepared and had obviously watched the film at least one again just beforehand in order to organize and sync up his thoughts. If you like Willow then I definitely recommend you listen to that, too.

Of those several hundred I've listened to there are two that I always recommend to people when the film they were done for is brought up: Roger Ebert's commentary for Citizen Kane and the actors' commentary for Willy Wonka. The former is because of how prepared he was and how informative it is. The latter is because of the sheer fun they are having (although I felt a little bad for the German guy - "Augustus Gloop" - who just got overwhelmed by how fast the others were talking, probably because English was not his primary language.)